Evolve or Die: Is this the End for Sword and Sorcery?

Can the genre ever move on from Robert E. Howard's Conan? How can writers possibly innovate within this narrow fantasy subgenre? Is the sword and sorcery barbarian facing his last stand?

BARBARIAN SOUP

A classic, no-effort comfort dish, handy for those back-of-the-cupboard ingredients a little past their sell-by date.

Writing time: 30 minutes

Serves: Men over fifty, lazy editors

Ingredients:

1 ripe barbarian + sword

1 wilted slave girl (clothes removed)

1 mad sorcerer + minions (you can substitute the traditional robed cultists for animated skeletons if you prefer a little crunch)

1 giant snake (or unknowable horror if you’re feeling exotic)

Serve in a ruined temple (sacrificial altar optional).

Each serving provides 72g repetitive combat, 82g straining thews, 500g nostalgia (of which 499g exhausted tropes), 0g originality, minus-1,000,000g imagination.

It’s the eternal challenge facing writers of genre fiction: how do I keep things fresh? How do I stop my vampires from feeling bloodless, my romance from running out of steam, my hard-boiled dick from going limp mid-investigation?

As I fight to clear a couple of weeks to pen a tale of my own, I’ve been reading Flame and Crimson (2019), a stirring and comprehensive survey of sword and sorcery fiction by the excellent Brian Murphy, and it’s got me wondering if the genre can ever escape its past.

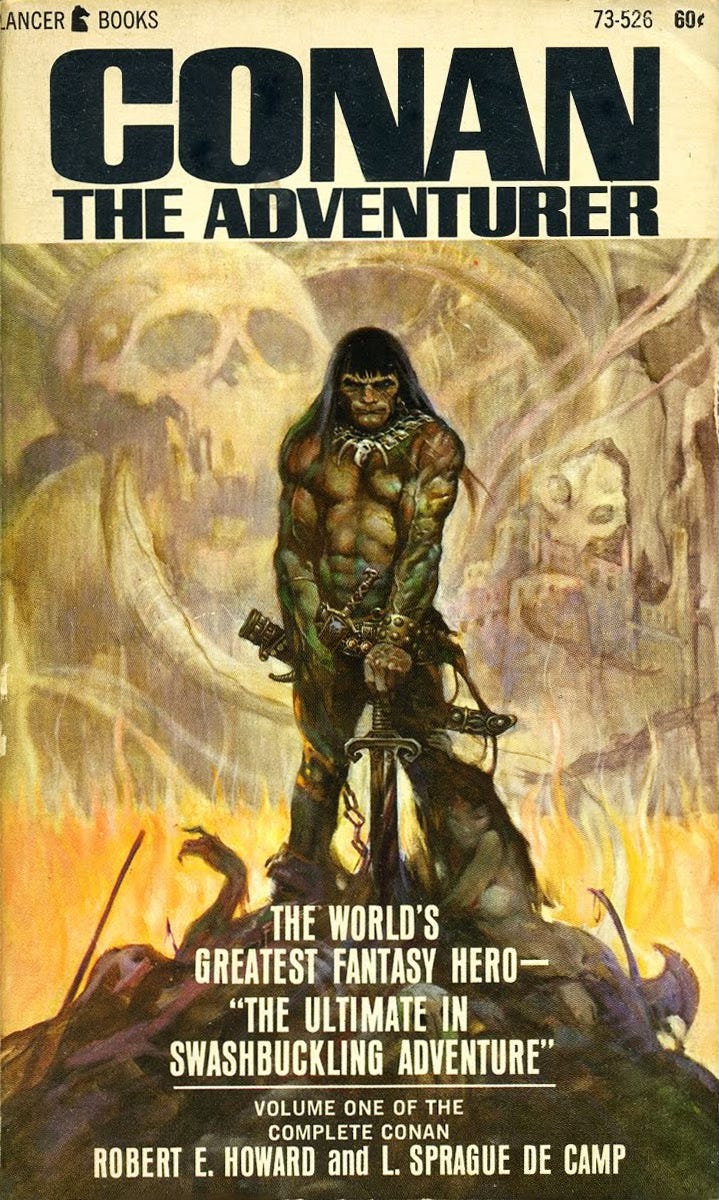

Murphy’s book charts the birth of sword and sorcery in the Depression-era pulps, striking its first resonant note in the 1929 tale The Shadow Kingdom by Texan author and poet Robert E. Howard. Alongside wistful Englishman J.R.R. Tolkien, Howard created one of the two towers of 20th century fantasy fiction: The Lord of the Rings and the short story adventures of Conan the Cimmerian.

Howard’s brooding yet fast-paced tales forged the sword and sorcery template as it’s recognised today: barbaric adventurers battling magic and monsters on the frontiers of doomed civilisation.

If Lord of the Rings is tea and scones, Conan is a mug of ale and a punch in the face.

Howard took his own life in 1936 at the age of 30 (by which time Tolkien was 44 and would publish The Hobbit the following year). He left behind hundreds of short stories, fragments, notes and poetry, a chaotic legacy that would be reprinted, rewritten, plundered, exploited, dismissed and cherished for years to come1.

Sci-fi fandom dominated the war years, up until the mid-1950s when Tolkien’s opus detonated an overall fantasy boom that would last for decades. Sixties sword and sorcery launched Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melniboné, a demonic, drug-addled rock star of a swordsman, along with the resurgence of Fritz Leiber’s cutthroat power-couple Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser2. Artist Frank Frazetta gave us the first modern rendition of Conan with a series of immortal covers for the Lancer reprints, which gave us the barbarian brute we recognise today3. By the 1970s, the genre was reaching audiences outside the paperbacks via Marvel Comics and first edition D&D.

By the 1980s, however, the ghost of Robert E. Howard was proving tough to exorcise. Writers, editors and the readers they served had come to idolise the genre’s godfather like the besotted flower-children of Thulsa Doom. Sword and sorcery stories had withered into weedy fanboy pastiche and cynical hackwork that possessed no trace of Howard’s trademark conviction4.

Tolkien-derivative, multi-volume breezeblocks like Terry Brooks’ Shannara and David Eddings’ Belgariad had conquered the fantasy bestseller lists, leaving the barbarian hero booking the last train to Valhalla in David Gemmell’s Legend (1984) and targeted for parody in Terry Pratchett’s The Light Fantastic (1986). When asked what is best in life, Pratchett’s elderly barbarian Cohen splutters through his few remaining teeth. “Hot water, good dentishtry and shoft lavatory paper.”

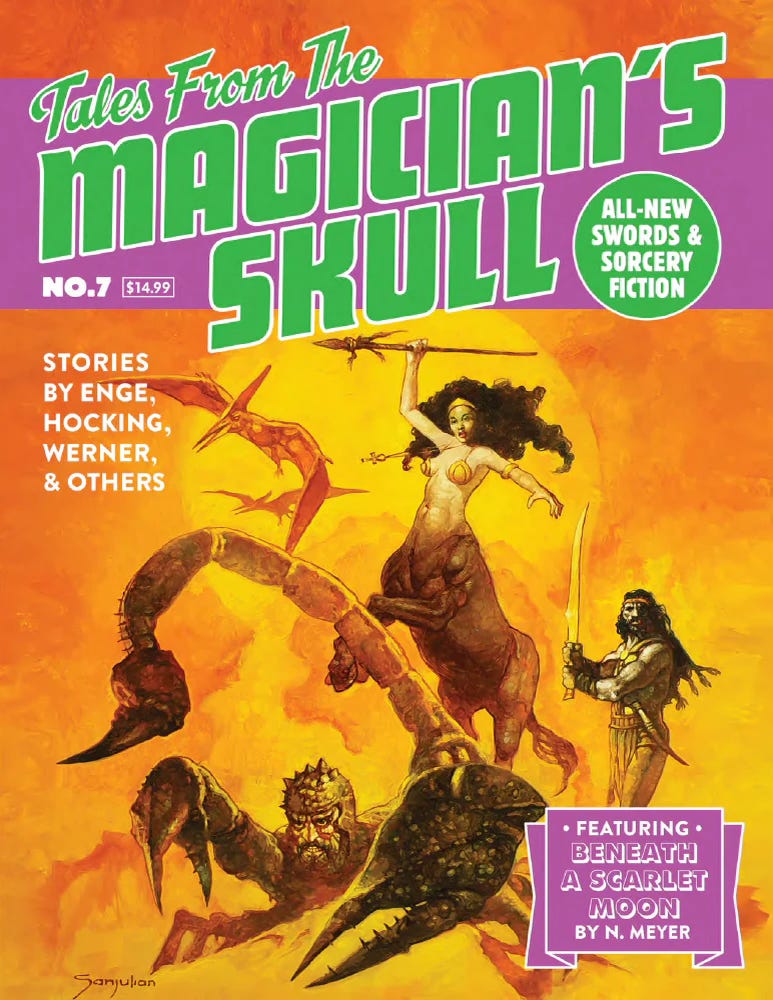

However, the digital age has seen sword and sorcery make an encouraging return to its roots in the periodicals. Crowdfunding, e-publishing and social media has made it easier than ever for fans of the genre to share their passion projects.

Pulp-spirited, crowd-sourced magazines are thriving right now, with titles including New Edge Sword & Sorcery, Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, the wonderfully titled Old Moon, Tales from the Magician’s Skull, Savage Realms and Whetstone, as well as hefty anthologies like A Book of Blades and Neither Beg Nor Yield!, and spirited, engaging podcasts like Rogues in the House.

And if you’re looking to keep up with this explosion of activity, then you’ll need to subscribe to

by .Along with superhero comics and D&D, sword and sorcery is yet another geek culture niche brought to mainstream attention by the internet, which means the genre is no longer dominated by the grognards, those veteran fans who have kept the genre alive for the best part of a century. Sword and sorcery is welcoming a new generation, those millennials who grew up with Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies, queued at midnight for the latest Harry Potter, and ignored homework to play World of Warcraft. Less fixated on Howard and more versed in the atomised culture of the internet, these readers are bringing their writing game to the table, offering more exploratory, less hidebound takes on the genre.

While this incoming generation of writers is figuring out how the genre speaks to them, their seniors are wondering how to tell a story without being crushed by the weight of sword and sorcery history in which they are so immersed. Both generations are asking the same question: How do I write a sword and sorcery tale that doesn’t feel like it’s been written a thousand times before? How can writers capture the crazed vigour and frontier spirit of the genre without it feeling like a Howard pastiche?

PRE-ORDER ‘NEW EDGE SWORD & SORCERY 2025’ Read my brand-new story featuring a brand-new hero appearing in print for the first time, alongside a host of fine fantasy authors

Back in the 1980s, Michael Moorcock railed bitterly about the influence Tolkien was having on epic fantasy, but these days everyone’s too busy trying to capture the grimdark of HBO’s Game of Thrones to really care too much about what the Professor might think. Even next to a spin-off show, House of the Dragon, the allegedly Tolkien-inspired Rings of Power feels almost laughably naïve. The killers and thieves of Sarah J. Maas’ Throne of Glass (2012) and Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows (2015) are raising armies of fans on BookTok and have little use for the moral clarity and Catholic quest narratives of Tolkien. Yet the image of Robert E. Howard’s roving barbarian remains ubiquitous when it comes to selling sword and sorcery comic books, RPGs, video games and board games.

Sword and sorcery’s most common format – the short story – may be restricting the genre’s wider appeal. As all writers know, agents don’t like short stories. But they are very keen on multi-series epic fantasy novels, which offer the space to explore multiple ideas in detail. The very richness of Game of Thrones (both the books and TV show) come from bringing to epic fantasy a very un-Tolkienian moral ambivalence. It’s amazing how much material you can get out of a stock fantasy character – the princess, the knight, the king – just by giving them a sex life. And how much that show’s appeal – the promise of violence and smokin’ hot bods – has been borrowed from sword and sorcery.

George R. R. Martin’s Howardian barbarian Khal Drogo may well have crushed the jewelled thrones of Essos beneath his horses’ hooves, but his death by sepsis is one unlikely to make it into the sagas. Such knowing subversion is also at work in Joe Abercrombie’s Logen Ninefingers, a barbarian living under the weight of his own murderous legend5.

While a great deal of sword and sorcery has bled into other genres – and other media; there’s a lot of Conan in the thriller series Reacher and the gonzo sci-fi of Mad Max: Fury Road – the genre’s traditional short story format still has a distinct creative advantage over its better-selling, long-form rivals. A good sword and sorcery tale has no room for flabby introspection. Tight as a Spartan six-pack, it’s built for speed and thrills and wonderment, fuelled by a spirit that’s pure outlaw pulp. You can keep your corporate epic fantasies. Continuity is for nerds.

READ: SWORDS, SORCERY AND THE SHE-WOLF In the age of corporate epic fantasy has pulp-era sword and sorcery become more appealing than ever? Wondering where the genre stands as I discover a forgotten fantasy heroine from the Marvel vaults

The iconography of sword and sorcery is as formalised as that of the Western, with which it shares an interest in mythologised history, rugged individualism and the wild frontier. But an iconography unexamined often falls prey to formula, especially when combined with the narrow demands of adventure fiction. A plot formula is a boon to the busy writer with a tight deadline and a looming rent bill6, which is one reason why the spinner-racks of the 1970s were crammed with so many ‘Clonan’ books. The Western produced just as many formulaic B pictures over the years, but it also gave us Red River (1948), Blazing Saddles (1974), Unforgiven (1992), Brokeback Mountain (2005), and Yellowstone (2018-), all very different explorations of the same stock material.

A genre is only limited by what a creator chooses to do with it.

And yet sword and sorcery has been dismissed down the years by some legendary authors, among them Ursula K. Le Guin, Michael Moorcock, even Stephen King, all of whom perhaps judged the genre on the merits of its worst examples. They might be forgiven for writing at a time when those worst examples were prevalent, but still. It’s like dismissing all Westerns just because you don’t like John Wayne.

Cyberpunk is another genre instantly recognisable by its tropes and just as prone to formula and creative block. “Nobody has yet imagined a way out of the typical cyberpunk dystopia,” states Guardian writer Paul Walker-Emig in Why Does Cyberpunk Refuse to Move On?

“Cyberpunk is being stripped of any political power it once had… Hacking: check. Cybernetic enhancements: check. Street crime: check. Punk fashion: check. Urban sprawl: check. These are all just cool cyberpunk symbols, rather than allegorical systems that need to be challenged.”

In other words, the author must bring meaning to tropes and stock characters.

“A writer of fantasy must be judged by the level of inventive intensity at which he or she works. Allegory can be non-existent but a certain amount of conscious metaphor is always there. The writer who follows such originals without understanding this produces work which is at best superficially entertaining and at worst meaningless on any level – generic dross doing nothing to revitalise the form from which it borrows.”

Michael Moorcock, Wizardry and Wild Romance (1987)

I’d argue that conscious metaphor – however well intentioned – can quickly become tedious, laboured and every bit as tiresome. I’d also argue that the power of Howard and Tolkien’s stories derive from just how un-conscious were their metaphors. But Moorcock’s point still stands.

A sword and sorcery writer must respond to the genre’s themes and values.

The epic fantasies of Middle-earth, Westeros and Arthurian Britain explore the grand interplay of national power and individual responsibility. Civilisation is what’s at stake, threatened by the unholy chaos of Sauron, the White Walkers and Morgan le Fey. The world of sword and sorcery is more ancient, its concerns more primal. The monsters of chaos are still fresh from the primordial ooze and still hold dominion over the land, yet to be vanquished by roaming culture heroes as barbaric as the leviathans they oppose. The kingdoms of the epic fantasy are still being built. The wilderness is yet to be tamed and colonised by those more ‘civilised’.

The sword and sorcery hero then is caught between ‘progress’ and the past, between corrupt civilisation and ancient sorcery. Lacking any political power, what else is there for such murder hobos to do but live in the moment - to eat, slay, love?

“I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.”

Conan in Queen of the Black Coast (1934)

It all sounds a bit like Rousseau’s condescending ‘noble savage’ theory, but there’s little that’s noble about these vagabonds and mercenaries. Sword and sorcery heroes fight not to save the Shire, but to stay alive, to know themselves.

From its roughneck roots in the pulps to its distrust of middle-class civilisation – personified by egotistic wizards, ineffectual kings and conniving viziers – sword and sorcery is working class to the core. Its heroes are bodies, first and foremost, romantic ideals of masculine or feminine power, Grecian in their magnificence. They are gorgeously rugged, animalistic in their perfection. They are proficient, confident, self-sufficient, swole, ripped, enviable. They are apex predators or at least apex survivors. They are totems, superheroes of their kind.

If Agent of Weird got you smiling, thinking, or ready to create, then please consider sharing, subscribing or throwing me a healing potion. Every drop of reader-support will help this project grow.

Sword and sorcery is often dismissed (by middle-class critics) as power fantasies. Indeed they are, but – as with all fantasy, whether fairy tale, urban or epic – we must ask the question, whose fantasy does this story fulfil? What is it that’s lacking? If Black characters hadn’t been voiceless in sword and sorcery for so long7, then trailblazer Charles Saunders wouldn’t have felt the need to create his Afro-centric hero, Imaro. If female characters weren’t always part of the drapery, we wouldn’t have Red Sonja. (Though let’s not give Roy Thomas too much credit here, as Sonja was invented primarily to give teenage boys like me the chance to ogle a chainmail boobie-hammock.)

Sword and sorcery lends power to the powerless. So who is it that feels helpless here? The reader? The author? Robert E. Howard certainly felt powerless when he was writing a century ago in oil-boom Texas. Howard yearned for the romance of the vanished frontier, the American mythology upon which he’d been raised. The strong male body - once prized by that hardscrabble generation – was now second in value to machines and industry. It was promised that oil would bring money and progress to his hometown of Cross Plains, civilisation, but to Howard it brought only corruption and carpetbaggers. Those observations, those feelings, those judgements struck a chord in Howard, who then dramatised those themes within his stories.

READ: EMPIRES OF THE IMAGINATION A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema from Georges Méliès to the Lord of the Rings by Alec Worley (McFarland, 2005)

It’s the themes that can make a sword and sorcery story ring like drawn steel. Barbarism vs. civility. Magic vs. muscle. Instinct vs. knowledge. Pagan vs. Christian. Self vs. selflessness. These are among the genre’s key concepts and they must be observed, agreed with, disagreed with, questioned, challenged, refuted, expanded, subverted, parodied. Sword and sorcery writers need an angle, a viewpoint that resonates. You don’t need to climb on your soapbox and start yelling at your readers. But you do need some kind of value judgement, or else you may as well leave your writing to the bots.8

Writers must ask questions of their chosen genre:

How do these stories usually play out? Take a detour.

What assumptions do these stories make? What never happens? What do you think should happen?

Who never gets to tell this kind of story? Who never gets to be the hero?

When/where do these stories take place? Go somewhere/somewhen else.

Who do these stories usually speak to? Speak to someone else.

What are the tropes and cliches? Expand upon them, subvert them, what happens if you get rid of them or make them the star of the show?

What never happens in these stories? What would happen if it did happen?

And, most important of all…

Who are the stock characters? What do you think of them? What do readers think of them? How do you think the characters feel about themselves, about being in this kind of world, in this kind of story? How do these types of characters speak to you on a gut level? An intellectual level? Can you relate to them? Can the bad guy be the good guy? The classic hero a villain? What have I never seen these characters do before? And how can I put them through hell?

It also helps if you understand pace, like inventing cool new monsters, and know which end of the broadsword your protagonist needs to poke them with.

The tools required to move sword and sorcery forward - to keep it thriving - are right here, but would some actually prefer to let the genre languish in the past?

As YouTube seems to delight in reminding me, every fandom possesses a howling minority of hardline gatekeepers, consumers seemingly lost to reason, who see the very existence - never mind the inclusion - of identities other than their own as political aggression, one that somehow threatens to scrub them out of existence. This, of course, is part of a broader conversation about algorithmic radicalisation, cultural paranoia, the outrage economy, and other forms of viral madness that descend on people like hallucinogenic fog and will always get in the way of the clear-headed focus demanded by good storytelling.

When I’m offline, wandering around book fairs and comic cons, when I talk to mates and peers who love sword and sorcery, I see a great many people who grew up just like me: cultureless, faithless, (fatherless,) male, white and working class9. I see blokes who got licks at school for liking this stuff, back when fantasy was dangerously uncool, who discovered the genre at an age when they craved girls, and men they could look up to.

But above all I see nostalgia. So what used to be in sword and sorcery that isn’t there now?

“We must restore the sense of the fantastic. Once magic is banal or easy, once magic rings can be found at the corner market and wizards are everywhere, sense of wonder goes straight out the window.”

Howard Andrew Jones, New Edge Sword & Sorcery, Fall 2022

The nostalgia I see in my generation is not for the ugliest excesses of the past, but for the feeling sword and sorcery fantasy evoked in us when we first discovered it, back before stories were called ‘IP’, before ideas became ‘franchises’, before Lord of the Rings and Conan were owned by corporate subsidiaries.

is a wonderful Substack curated by , who gleefully showcases all manner of unearthed arcana, from tatty adventure modules covered in notes scribbled by kids back in the ‘70s to novelties you saw once in a magazine but never got your hands on, a treasure trove of fantasy ephemera - truly, a bazaar of the bizarre.Rediscovered Realms celebrates that lightning-bolt that strikes the fan upon their first contact with fantasy… that sense of wonder, of the intangible and ineffable, of that I-dunno-what-the-heck-this-is-but-it’s-the-coolest-thing-I’ve-ever-seen-in-my-life!

It’s that revelatory sense of discovery we felt when the boundaries of sword and sorcery were still swathed in swamp-mist, when dungeons were yet to be mapped, monsters yet to be catalogued, when the land felt unfamiliar, ripe with strangeness and danger.

It’s that “sense of the fantastic” that is the essence of sword and sorcery and its best writers know when to tantalise rather than explain.

READ: TOO MUCH MAGIC: THE PITFALLS OF WRITING FANTASY Anything can happen in a fantasy story. So how can writers prevent theirs from spiralling out of control?

As Brian Murphy cautions in his 2023 blog post Are We In a New Sword and Sorcery Renaissance?, the current resurgence of enthusiasm for this stuff is mainly taking place among the fandom and not yet the wider commercial market. In his 2021 post What Sword and Sorcery Needs, Murphy offers a wish-list of requirements for wider commercial success, namely more readers, maybe some big-brand authors, a passionate fanbase (check). Oh, and some genre-focused awards would be nice, along with some kind of mainstream crossover success (which The Witcher didn’t quite achieve).

Yet none of this is possible without the writers. How can sword and sorcery evolve? By cherishing those with different ways of thinking, whether those writers are coming from a different background or have different experiences, wider influences. A good writer always questions their genre, however much they adore it, however comforted they feel by it.

To keep sword and sorcery alive, its writers must challenge it.

As M. John Harrison says on writing genre fiction. “Ask what [the genre is] afraid of, what it's trying to hide – then write that.”10

Stay weird.

Black Beth: Vengeance Be Thy Name collects the first five tales, including the rare original 1970s strip by Conan cover artist Blas Gallego, three shorts from the rebooted series by Alec Worley and DaNi - Magos of Malice, The Witch Tree and Fairy Tales - and the incredible 48-page one-shot The Devils of Al-Kadesh, plus pin-art and more, available from Amazon, the Rebellion webstore and all good comic shops.

“An absolute blast… classic sword and sorcery…” Hypnogoria.

“A fast-paced, straight-faced, sword and sorcery adventure… a love letter to the genre in all its glory.” Big Comic Page.

“Brilliant!” The Awesome Comics Podcast

“Fabulously enjoyable sword and sorcery… Simply wonderful stuff… A visual tour-de-force… Essential Reading.” Comicon.com

“Fans of dark, epic fantasy will surely love this book.” Cemetery Dance

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

For the full story of Howard’s troubled literary legacy, I’d recommend the excellent 2013 biography Blood & Thunder by

.This adventurous duo first appeared in 1939 in the pages of Unknown.

Before Frazetta, Conan tended to be depicted more like a dashing matinee idol.

With a few very notable exceptions, namely Charles Saunders, Tanith Lee and Karl Edward Wagner.

From Abercrombie’s deliciously characterful First Law trilogy, The Blade Itself (2006), Before They Are Hanged (2007) and Last Argument of Kings (2008).

Moorcock’s favourite is the Lester Dent Master Plot.

Read “Die, Black Dog!” A Look at Racism in Fantasy Literature, a 1975 essay by Charles Saunders.

Please don’t!

Horny white boys of limited means have been a key demographic for sword and sorcery publishers since the days of Howard, so it comes as no surprise that we’ve dominated the fanbase for so long.

Dear Alec --

God DAMN, this is an excellent piece! I don't even have a horse in this race. But everything you say about the differences that make all the difference rings 100% true for ANY genre that doesn't want to disappear up its own ass, inbred and tedious, its true glories forgotten.

Once again, I applaud you. This is the kind of thoughtful, razor-sharp kickass writing that might actually get me to pick up a sword-and-sorcery book again. But only if it was this fucking good.

Yer happy pal in the trenches,

Skipp

A lot of the “gatekeeper complaints” are an answer to an attitude that older stories or IP are not merely old-hat or full of now-overdone tropes, but so problematic that they should be buried (it gets even more toxic when it’s tied to demographics, such as treating a work as trash because a straight white male wrote it.) You see it with classic IP in particular; many new installments are deliberately made to upset older fans and “fix” an IP the new owners consider “broken.”

**That said,** I agree with your post. Genres do need to change to stay fresh; we can’t be writing the same thing all day every day. I do not oppose publications that seek to evolve beyond the foundations established by Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber; rather, I don’t think that older work and classic authors should be treated as problematic poison, even if you’re not fond of them and believe them to fall short. You did well to make a case for the older work, and I do believe that there is room for everyone since it’s not like Sword & Sorcery is tied to any one publication.