Vampires Don't Have to Be Horrible

How Guillermo del Toro’s Cronos (1992) subverted the bloodsucking genre

God bless Guillermo del Toro, patron saint of the fantastic. Creators of the weird and wonderful should have a candlelit icon of the Mexican maestro framed above their desk, his boyish mop haloed with tentacles, a third eye peering from an open palm, owlish behind those glasses, bearded and beaming like an eldritch Santa. He’s one of our greatest living fantasists, the monster kid made good. As an Oscar-winning filmmaker, artist, producer, writer and fanboy, he balances a child’s love of the lurid with the artist’s grasp of what it all can mean. As critic Michael Atkinson puts it, “He’s as much a descendent of Borges, mad for ancient anti-science and reflective labyrinths, as he is an heir of EC comics.”1

His output straddles the popular (Hellboy [2004], Pacific Rim [2013]) and the personal (Pan’s Labyrinth [2006] remains his masterpiece with The Devil’s Backbone [2001] a close second, while The Shape of Water [2017] finally won him Oscars for Best Director and Best Picture). His name carries clout enough to headline TV shows (Trollhunters [2016-18], Cabinet of Curiosities [2022]), but he’s so far resisted being subsumed by his own brand. He remains an icon of the bizarre, an artista of the arcane, a santo of the strange.

And it all started with his micro-budget, debut Cronos (1992).

Made when del Toro was in his late twenties, this vampiric fairy tale lacks the finesse of his later films, but its talons sink deep, establishing del Toro’s trademark obsession with beatific monsters, ecstatic horror, gold-plated gimcrack, and the insectile banality of evil.

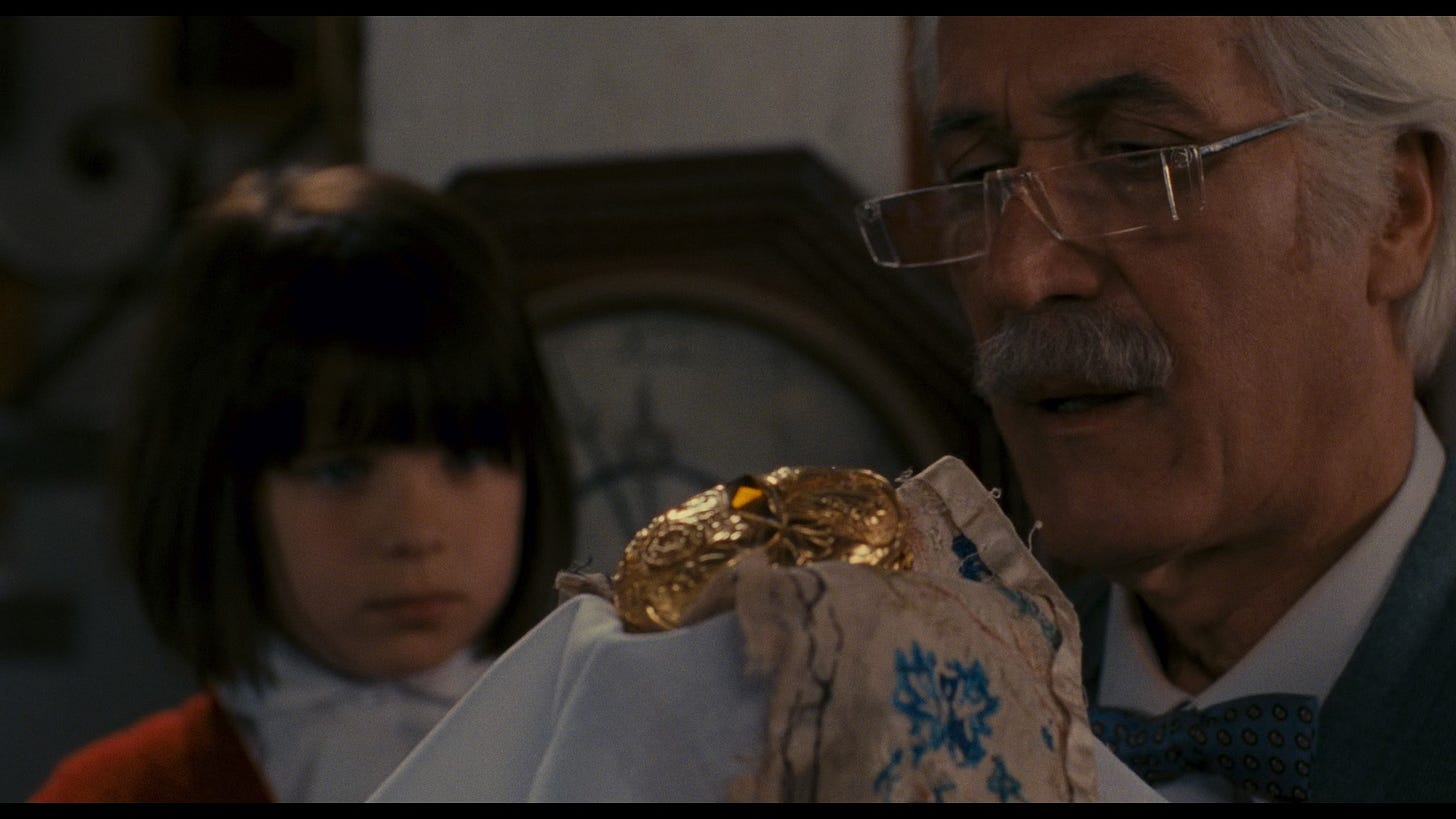

A 16th century alchemist2 flees the Inquisition and settles in Mexico where he fashions a bloodsucking clockwork scarab capable of granting eternal life. Stashed inside the bust of an archangel, the gold-plated doodad is discovered four centuries later by aging antiques dealer Jesús Gris (a gently determined performance by the late Federico Luppi, a legend of the Latin American screen).

While Jesús spends his autumn years doting over his mute granddaughter, grasping industrialist Dieter de la Guardia (Claudio Brook, another legend) spends his time in germophobic seclusion, barking orders to seize the so-called Cronos device in the hope it will save him from cancer.

Ron Perlman plays de la Guardia’s nephew, a preening knucklehead sent to fetch the device, which has already sunk its spring-loaded claws into Jesús’s veins. Now it’s Christmas-time and Jesús has found himself reborn with a decidedly unholy thirst.

Mexican horror cinema had entered a general decline by the late 1970s3, as the government reduced state funding and generally favoured more respectable fare. By 1991 Mexico’s feature film output had shrunk to a mere 34 movies, most of which were produced by the two dominant production companies, Imcine and Televicine, neither of which liked horror. It took del Toro eight years to get Cronos off the ground, three of which he spent negotiating with Imcine, who wouldn’t sign a cheque until del Toro had not only storyboarded the entire project, but also built a prototype of the Cronos device itself.

Another $600k in funding had been promised by an American producer, but the cash never materialised, and Cronos was left stranded half-way through filming. Ron Perlman agreed to carry on without pay4, while del Toro was forced to take out a loan against his house.

The finished film so appalled Imcine that they banished del Toro to Cannes with nothing more than a handful of posters, a roll of Scotch tape and the certainty that he’d return with a grovelling apology for wasting their time. Del Toro came back months later with ten international awards, including the Mercedes-Benz Award from Cannes.

Cronos offers a striking, original take on the vampire myth. Like the Cronos device itself, the movie is a work of grand Catholic baroque rendered in miniature, infested with secretive details and radiant with symbolism. Indeed, it chases so many themes that it often lacks focus, but is never less than fascinating. Here the curse of vampirism is passed on not by an older vampire, but by a mysterious Lovecraftian bug that nests inside the gilded shell of the device itself. We half-see it pulsating like a blackened lung surrounded by whirring, exquisite clockwork.

This blasphemous trinket suckles at Jesús’s breast like a bloodsucking infant, its sticky venom serving to smooth his jawline and improve his libido but reducing him to a helpless addict. As in Robert Egger’s wonderfully fetid Nosferatu (2024), there’s nothing remotely sexy about blood-drinking here. In a revolting sequence, Jesús follows a man with a nosebleed into a swanky bathroom where he fingers a dollop of blood on the marble sink like he’s dabbing at a wrap of coke. When he's on his hands and knees lapping blobs of plasma off the floor, we’re not meant to envy him the way we do the undead hotties of Interview With A Vampire or True Blood, but rather mourn the kindly gentleman we’ve now lost.

Jesús is no longer human; he is nothing but appetite.

Nor does eternal life come with eternal beauty. When Jesús eventually returns from the dead he’s appalled to find that vampirism – like the elixir of life in Death Becomes Her (Robert Zemeckis, 1992) – fails to airbrush one’s mortal wounds. With his funeral suit on backwards and mortician’s staples punched into his cheeks, he staggers home to his granddaughter. But the scene plays not for terror, but tenderness, as the little girl stashes him in her toybox with a teddy tucked under his arm, safe from the scorching sunlight.

Vampire movies aren’t often told from the point of view of the (non-vampire) senior citizen. A youth-focused movie like The Lost Boys (1987) revels in loud music, edgy fashion, gorgeous faces, great sex, and the feeling of wanting it all to last forever. The elderly main character of Cronos has already suffered the loss of that youthful vigour; he flirts with immortality because he wants it all back. The lesson he learns is that to resist death is to become a monster, like the American moneybags de la Guardia. Instead, Jesús refuses his grisly impulses, finds solace in family, and accepts oblivion with dignity.

Del Toro dedicates the film to his late grandmother.

Cronos has a faith in humanity that restrains it from becoming all-out horror. As Kim Newman puts it in Nightmare Movies. “Cronos peers deeper into the dark traditions of South-of-the-Border horror, tapping into the familial theme of the Crying Woman cycle – la llorona weeps because she’s done the terrible thing Jesús Gris is strong enough to hold back from, murdering a child of her own blood.”

Cronos is too heroic to be horror, too heartfelt. Like the bulk of del Toro’s work, it’s more gothic fantasy than terror tale. It makes no thrilling flight from death but instead welcomes it with a warm and hard-won smile.

Stay weird.

Cronos is available from the British Film Institute on limited edition UHD and Blu-ray, scanned and restored using the original 35mm negative under the supervision of Guillermo del Toro himself. Special features include del Toro’s 1987 short film Geometria and a 60-page perfect-bound book of critical essays, along with eleven new and archive interviews and commentaries with the director, cast and crew.

Available for pre-order from the BFI shop in UHD and Blu-ray.

Review copy provided by the British Film Institute.

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

Film Comment, 2007.

Based on the real-life French occultist known as Fulcanelli, versions of whom show up in a couple of notable Italian horror films, Michele Soavi's La Chiesa / The Church (1989) and – as Kim Newman points out in his indispensable book Nightmare Movies – provides the model for the diabolic architect Varelli in Dario Argento’s Inferno (1980).

A whistle-stop tour of Mexican horror movie history begins with La Llorona / The Crying Woman (Ramón Peon, 1933), the country’s first major horror movie and the first to adapt the tale of the nation’s signature spook. Next, El Fantasma del Convento / The Phantom of the Convent (Fernando de Fuentes, 1934), a tale of benighted travellers seeking refuge at a sinister monastery.

The 1960s are widely considered the Golden Age of Mexican horror cinema, a revival kick-started by the success of two movies directed by Fernando Méndez: Ladrón de Cadáveres / The Body Snatcher (1957) and El Vampiro / The Vampire (1957). Mendez directed another macabre milestone Misterios de Ultratumba / The Black Pit of Dr. M (1958), about conniving scientists vying to discover what lies beyond death.

Mummy movies here are of a pleasing Aztec flavour, notably the campy trilogy of cheapies directed by Rafael Portillo in 1957: La Momia Azteca / Attack of the Mayan Mummy, La Maldición de la Momia Azteca / The Curse of the Aztec Mummy and La Momia Azteca vs el Robot Humano / The Robot vs the Aztec Mummy. Connoisseurs of truly gonzo cinema will love Chano Urueta’s El Espejo de la Bruja / The Witch’s Mirror (1960) El Barón del Terror / The Brainiac (1961). Both completely bonkers!

Monsters were a common feature of the many El Santo movies, the superheroic adventures of Mexico’s iconic luchador, suicide-diving horror icons alongside his buddy the Blue Demon in movies like Santo y Blue Demon Contra los Monstruos / Santo and Blue Demon vs. the Monsters (Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1970) and Santo y Blue Demon Contra Drácula y el Hombre Lobo / Santo and Blue Demon vs. Dracula and the Wolf Man (Miguel M. Delgado, 1973).

Two major horror filmmakers emerged, both a huge influence on Guillermo del Toro: Carlos Enrique Taboada (1929-1997) and Juan López Moctezuma (1929–1995). Alucarda, la Hija de las Tinieblas / Alucarda, the Daughter of Darkness (1977) is widely regarded as Moctezuma’s masterpiece, a feverish tale of convent-bound possession loosely adapted from J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s sapphic Victorian vampire classic Carmilla. Taboada was instrumental in modernising the Mexican horror film, bringing the ghosts of the gothic past into the present-day with his quartet of sublime supernatural horrors, Hasta el Viento Tiene Miedo / Even the Wind is Afraid (1967), El Libro de Piedra / The Book of Stone (1968), Más Negro que la Noche / Blacker Than the Night (1974) and Veneno Para las Hadas / Poison for the Fairies (1984).

Today, Mexican horror cinema continues to thrive. Check out KM31 (Rigoberto Castañeda, 2006), a creepy update of the Weeping Woman story, slippery psycho-sexual tale The Untamed (Amat Escalante, 2016), Tigers Are Not Afraid (Issa López, 2017), a brilliant, del Toro-esque fantasia about childhood amid cartel violence, and Huesera: The Bone Woman (Michelle Garza Cervera, 2022), a raw maternal nightmare.

For which del Toro thanked him by making him a fixture of his later movies, including the title role in his mega-budget Hellboy movies.

Such a great movie. I feel like it had to be part of the inspiration for Midnight Mass, lotta commonality there.

After Pan's Labyrinth, Cronos is still my second favourite of del Toro's movies. Sometimes a shoestring budget really helps.