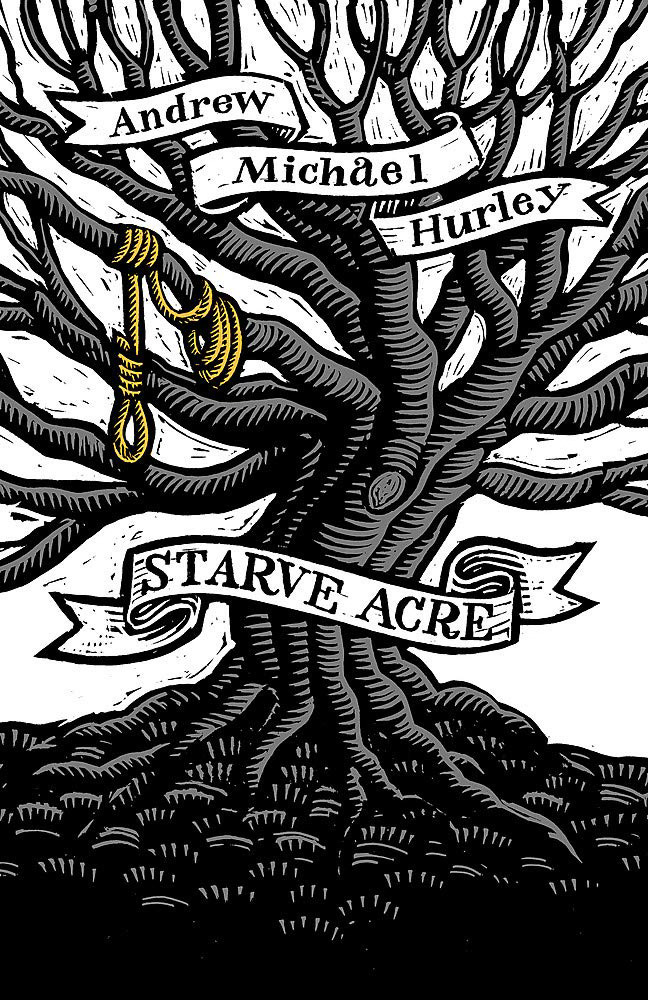

Aces of Weird: Starve Acre (Andrew Michael Hurley, 2019)

This bleak and atmospheric folk horror novel unearths new horrors in old haunts

Somewhen in the 1970s, Richard and Juliette Willoughby moved to the Yorkshire countryside seeking a land of greenery and pleasantries in which to raise Ewan, their young son. Instead, Ewan dies and the land inherited by his grieving parents yields nothing but ghosts. The dour farmhouse and adjoining field – a mysteriously barren plot known hereabouts as ‘Starve Acre’ – becomes, like Shirley Jackson’s Hill House, a haunting symbol of shared psychosis.

“Another bend, a steeper rise, and then the lane flattened out and Starve Acre came into sight, its three storeys clad in heavy stone, the windows shuttered, the front door a utilitarian black. Happened upon like this, it was an ugly place, Richard always thought. A place to peer at from a moving car and let dwindle in the rear-view mirror thinking about the poor souls who lived there. On the edge of a moor, it was like a lighthouse, conspicuous and solitary. And now that Richard’s mother had gone, it felt as if the very last dregs of life there had dwindled away.”

Richard and Juliette are broken by grief, now as distant and inscrutable to each other as beings on either side of a Ouija board. Juliette believes she can hear her dead son scampering about their home. Desperate to contact him, she reaches out to a family friend connected to a coven of cosy occultists. Meanwhile, archaeology professor Richard buries himself in digging, compelled to search the field for his own father’s obsession: the remains of a legendary hanging tree.

Both seek answers, an explanation for their loss, but Starve Acre has nothing to give them but the unexplainable.

As a treatise on grief, Starve Acre is powerful, evoking loss as something that can grow immense and malevolent, burying its victims alive. The book ticks every folk horror box, but transcends the gothic trappings of wicker monsters and pub landlords prancing around in wooden masks.1

Author Andrew Michael Hurley has trod such unholy soil twice before, with the bleak British coastline of The Loney (2016) and the fiend-haunted moors of Devil’s Day (2017). Starve Acre is the third novel in this folk horror triptych.2 And, again, Hurley’s flinty prose demonstrates a mastery of place and isolation, a yeoman’s eye for the land.

“Overnight, snow had fallen thickly again in Croftendale and now in the morning the fells on the other side of the valley were pure white against the sky. Further down, where the sun had not yet reached, the wood by the beck was steeped in shadow and would stay cold all day. The freezing mist that was twined between the leafless beech and birch had already driven a hungry fox to seek food elsewhere. A line of deep paw prints came out of the gloom and into the pearly light that washed over the drifts on this side of the dale. […]

The storm had lasted for hours and the extent of its fury was marked by icy cornices blown over the dry-stone walls. They were wild jagged crests, like those of a sea surge breaking on inadequate defences.

So the winter went on. Adding to itself day by day. Making the houses in the dale seem even more remote from one another than usual.”

Starve Acre channels British folk horror’s unsentimental view of the rural as a place unmappable, untameable, and ultimately unknowable. Reading it, you feel like one of those posh, blustering hikers in M.R. James’s short story A View From a Hill (1925), peering through a pair of occult binoculars at scenes from Britain’s arcane past. Starve Acre may be set in the middle-class 1970s, but its view of the rural is pre-industrial and proletariat. Our urbane protagonist – sceptical, even hostile to his wife’s insistence that they arrange a séance to contact their boy – is forced to regard the land less like a smug academic and more like a medieval serf leaving timid offerings at the forest’s edge to appease what lays within.

“‘You do know they used the tree for hangings, don’t you, Richard?’

‘Yes, Gordon.’

‘That’s the reason nothing grows there in your field.’

‘Yes, Gordon.’

‘There’s not an inch of soil that’s still alive.’

Local lore had it that the divine reprisal had not ended with the tree but had spread out across the common in a poisonous ripple, turning the grass black, seeping down into the earth like oil, suffocating the life out of the place.“

Time had inevitably fattened the myths about Starve Acre, and yet it was undeniably sterile – most noticeably in the summertime, when all along the dale the fields belonging to the Burnsalls and Drewitts and Westburys were verdant and the Willoughbys’ plot was nothing but dry mud.

In all the digging he’d done, Richard had never once turned up a single worm or spider. Only bones.”

Like many a long-form supernatural tale – Richard Matheson’s A Stir of Echoes (1958) comes to mind – Starve Acre is a mystery story. What’s going on? How did Ewan die? What did he see out there in the field? What did he do to poor little Susan Drewitt? Is any of this even real?

Hurley hooks his backstory up to a drip-feed and delivers his clues piecemeal, slowly building an ever-puzzling puzzle. But those clues aren’t provided by visits to the library, sifting through newspaper clippings, or interviewing that sinister vicar with an eyepatch and a suspiciously extensive knowledge of Ye Olde Gods.

Instead of having Richard turn amateur detective, Hurley uses the emotional arc of his main character as a backstory-delivery system, focusing not on hackneyed plot mechanics but on character development. Richard’s reticence, scepticism, and denial over what may or may not have happened to Ewan, provides the vital pushback required to stop all that backstory - of which he’s already aware - from blurting out at once.

As Richard unearths more details and he and Juliette witness seeming miracles, so Richard’s resolve crumbles a little more, triggering another memory he'd rather not face, giving us another revelatory flashback. In this way, the book lays out the fragments for us to piece together, inviting the reader to join in casting the spell that makes the bones of this story stir with life.

Starve Acre is worth reading for its compulsive suspense and the chilly elegance of Hurley’s writing alone. Like Jackson and James, he’s also a master of suggestion and can land a shock with a single knockout line. But it’s his feeling for shared human pain and the strange territories it creates that haunts long after the final page.

Enjoy! And stay weird.

Starve Acre is available from World of Books, Amazon and Audible and has been adapted by writer/director Daniel Kokotajlo (Apostasy) into a movie starring Matt Smith and Morfydd Clark, released in the UK on 6th September.

READ: M.R. James and The Craft of Fear Learn the subtleties of writing terror from a master of the scary ghost story

To find out more about me, my books, comics and other projects, click on my LinkTree

The term ‘Folk horror’ was brought to popular attention by Mark Gatiss in his wonderful three-part documentary A History of Horror (2010), though it was first coined by writer Rod Cooper in his 1970 review of Blood on Satan’s Claw. Like sword and sorcery and cyberpunk, folk horror is a subgenre commonly identified by very narrow, very specific characteristics, and whose growth is often stymied by authors too in love with its tropes to see what they actually mean.

Starve Acre was originally commissioned as a playful horror pastiche for Dead Ink Books; this version was rewritten from a less splattery, more psychological angle for publishers John Murray.

Finally read Starve Acre last week, and it was really well done and I was able to borrow it from the public library, which is pretty amazing, since our library system is a bit short on horror. I loved it and have his newest book waiting to be consumed. Yum!

I literally just finished reading this yesterday after seeing the movie the day before. I'd highly recommend watching the movie after reading the book. It's slightly different and tells the story a bit more liberally. Matt Smith and Galadriel are great in it