The Furry Folk Horror of Watership Down (1978)

How the animated adaptation of Richard Adams’s novel terrified a generation and builds a non-human epic fantasy that casts a dark and enthralling spell

Presented with what was ostensibly a cartoon about talking bunny rabbits, the British Board of Film Classification declared in 1978, “Animation removes the realistic gory horror in the occasional scenes of violence and bloodshed… while the film may move children emotionally during the film’s duration, it could not seriously trouble them.”

Watership Down was duly awarded a ‘U’ certificate – suitable for all – and a cult movie was born.

Released in the October half-term of 1978 and first aired on the BBC over the 1985 Christmas hols – just before bedtime – Watership Down hit younger viewers like a vision of the apocalypse. Children raised on Bugs Bunny and Peter Rabbit were unprepared for the movie’s naturalistic savagery, replete with nightmare imagery straight out of The Shining. It was ruthless in its depiction of life on the lower rungs of the food-chain, a view of the world through the eyes of its most vulnerable; no wonder children responded to it so strongly.

The source novel was published in 1972, when author Richard Adams had only just turned fifty and spent most of his life as a civil servant. The tale of a colony of rabbits forced to undertake a dangerous odyssey across the English countryside in search of a new home, it was published and marketed as an adult novel, yet won two prestigious awards for children’s fiction (the Carnegie Medal for Writing and the Guardian’s Children’s Fiction Prize).

The book sprang out of tales that Adams rattled off for the amusement of his daughters during long car journeys between London and Stratford Upon Avon. At the girls’ insistence, Adams got those stories down on paper, developing his own leporine mythology and invented language, while drawing upon Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces1 to embrace eternal themes of (male) heroism, mortality and nature.

An immediate hit, Watership Down sold 100,000 copies in the UK (from an original print run of 2,500) and spent eight months on The New York Times Best Seller list. Adams sold the film rights to American producer turned director Martin Rosen.

Two years later, Rosen had adapted the book into a British animated feature at a time when British animated features were virtually non-existent.

Rosen initially selected American animator John Hubley to direct. By then, Hubley (along with his wife Faith) was a three-time Oscar-winner and multiple Oscar nominee, who began his career at Disney in 1935 and went on to create the famously myopic Mr. Magoo.

Cloistered in a shabby workshop in London’s Fitzrovia, Hubley worked on Watership Down from 1975, but was fired by Rosen a year later. Hubley was unable to discuss the matter due to legal proceedings, though he was later interviewed by animation historian Michael Barrier2 who observed, “it seems plain that Rosen wanted a more violent and emotional film than Hubley was prepared to give him.”

Despite having zero experience in either animation or direction, Rosen decided to helm the project himself.

Rosen’s movie opens sweetly enough, with a storybook telling of rabbit-kind’s creation myth, how the sun-god Frith created the world and all its creatures, how a bunny folk-hero named El-ahrairah was punished for his hubris with the creation of the hawk, the fox and other predators, but also blessed with the gifts of speed and cunning, so that his people might endure.

“All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a Thousand Enemies, and when they catch you, they will kill you… But first they must catch you.”

The movie’s life-and-death stakes have you by the throat as it opens out onto the real world of the North Wessex Downs3. Here the ‘Golden Afternoon’ of Lewis Carroll becomes a blood-drenched survive-o-rama closer to Conan the Barbarian than Alice in Wonderland.

A shaky young rabbit named Fiver (voiced by a tremulous Richard Briers) beholds rivers of blood pouring down the hills, prophesising an oncoming catastrophe that threatens his colony’s warren. He convinces his cunning older brother Hazel (John Hurt, lending the same rangerly tones he gave Aragorn in Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 Lord of the Rings), along with several others, including a heroic bruiser named Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox, who also voiced Bakshi’s Boromir).

Fleeing their warren in search of Fiver’s promised land, the rabbits make their desperate exodus across the home counties, barely surviving beast-haunted woods, speeding cars and strangling snares (the kids got to watch one of their favourite characters choking on his own blood as his comrades scrambled to save him). Death strikes this rapidly dwindling fellowship from all directions. Birds of prey snatch away the innocent in puffs of fur. Graveyard rats tear at their ears. Shotgun-toting farmers blow them away.

The movie’s pace is unrelenting, pitiless in its regard for our cuddly heroes. Few movies – let alone children’s favourites – do such a tremendous job at evoking the breathless terror of the hunted. Perhaps this tightness has something to do with Rosen’s script cramming in so much from a source book of over 600 pages (and somehow managing to make very little feel lost).

Propelled by Fiver’s shamanic visions and haunted by the shadow of the Black Rabbit of Inlé – rabbitkind’s own Grim Reaper – the movie’s quest story has a feverish sense of magic and the supernatural, creating an epic fantasy in miniature within the cosy hedgerows of England. Yet nothing in this green and rarely pleasant land is invented; only the rabbits’ perspective and culture. Fiver, Hazel and co. have their own folklore and customs, their own views on society. They’re baffled by the purpose of roads and believe speeding trains to be messengers of Frith. Watership Down presents not a secondary world, but rather a secondary world-view.

In the second half of the movie, the rabbits find themselves in trouble with local despot General Woundwort (Harry Andrews), a terrifying, one-eyed fascist who rules the dystopian warren of Efrafa. As the rabbits launch a daring rescue of several captives, the story ventures into allegory like other, more comprehensive animal fables like Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus and Orwell’s Animal Farm (itself made into a British animated feature in 1954), depicting animal society as a means of reflecting the foibles of our own.

Adams was called up in 1940 and served in the 250 Light Company, Royal Army Service Corps, 1st Airborne Division, notably at the Battle of Arnhem. Though he based several characters on the men with whom he served4, Adams – like Tolkien – always maintained that his novel was no wartime allegory. “It’s just a story about rabbits,” he said. In an interview with BBC Berkshire, he stated, “It's simply a tale… it's in no sense an allegory or parable or any kind of political myth. I simply wrote down a story I told to my little girls.”

Yet Watership Down the movie is entrenched in the iconography of World War Two, with its lop-eared Fuhrer, bloody massacres and gasping Auschwitz nightmares.

Two more animated epic fantasies, Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards (1977) and Lord of the Rings (1978), similarly feature Nuremberg addresses and tramping jackboots, not forgetting all that Triumph of the Will business at the end of George Lucas’s Tolkien/Campbell-influenced Star Wars (1977).

All these movies were released in the late seventies, an era when the threat of Western fascism must have felt enviably distant.

“I sometimes think that as Britain declines, dreaming of a sweeter past, entertaining few hopes for a finer future, her middle classes turn increasingly to the fantasy of rural life and talking animals, the safety of the woods that are the pattern of the paper on the nursery-room wall. Hippies, housewives, civil servants, share in this wistful trance; eating nothing as dangerous or exotic as the lotus, but chewing instead on a form of mildly anaesthetic British cabbage. If the bulk of American SF could be said to be written by robots, about robots, for robots, then the bulk of English fantasy seems to be written by rabbits, about rabbits and for rabbits.”

Michael Moorcock, Wizardry and Wild Romance (1987)

Moorcock was no more a fan of Adams’s book than he was of the bourgeois pastorale of Tolkien, though Rosen’s adaptation is far from docile.

What gives the movie such resonance, what makes its story so riveting is that Death abounds. The charcoal spectre of the Black Rabbit lurks everywhere, reminding us of the characters’ terrible fragility. Indeed, with its flinty themes of sacrifice, death and rebirth, Rosen’s Watership Down has more in common with the pagan folk horrors of The Wicker Man (1973) and Starve Acre (2023) than Songs of Praise and The Antiques Roadshow.

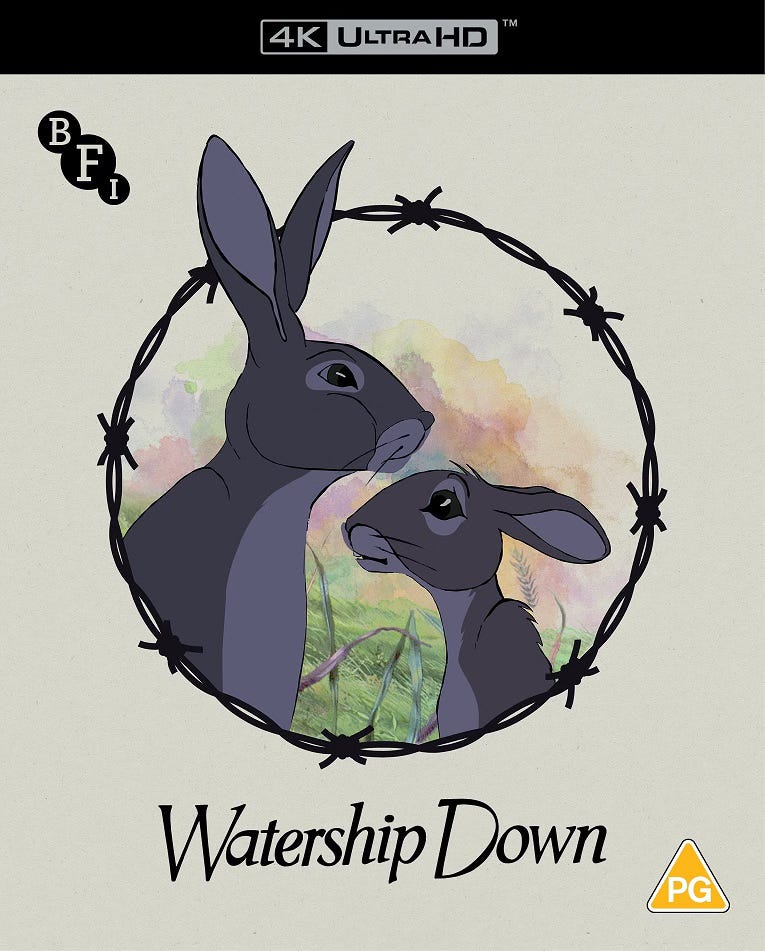

Death is right there on that sinister, original poster; did you notice the snare around the rabbit’s neck?

Wombles songwriter Mike Batt was commissioned to produce the movie’s wrenching theme song, Bright Eyes, sung by Art Garfunkel. In an interview with film critic Charlie Brigden5, Batt explained, “John Hubley said ‘I’d like you to write a song about death.’ I went home and I just thought, how the hell do you write a song about death without it being morbid or too dark? And then I thought it’s the big thing we all ask. One of the most important questions in most of our lives is what happens when you die?”

The commission came at a time when Batt was losing his father to cancer. “The words ‘bright eyes’ came into my mind, thinking about how bright the eyes are before they suddenly aren’t anymore. Later in life, I saw my dad after he died and it came round to me really strongly at that point that that’s what happens, that the eyes just lose all life and you know there’s no life in that person any more. And that’s what the song is about.”

“Is it a kind of dream?

Floating out on the tide

Following the river of death downstream

Oh, is it a dream?

“There's a fog along the horizon

A strange glow in the sky

But nobody seems to know where you go

And what does it mean?

Oh, is it a dream?

“Bright eyes, burning like fire

Bright eyes, how can you close and fail?

How can the light that burned so brightly

Suddenly burn so pale?

Bright eyes.”

Bright Eyes lyrics by Mike Batt

The song fades in when Fiver receives news that Hazel has been shot. Refusing to believe he’s dead, he follows the spectre of the Black Rabbit into the twilight mists in the hope of saving his brother. Batt’s dreamy lyrics are sung with angelic tenderness by Art Garfunkel, as Fiver’s pursuit dissolves into a surreal montage. Hazel’s body turns into a swirl of autumn leaves and bleeds back into the soil as the airy melody resonates not with despair, but wonder. There’s no fear, only an enticing strangeness.

The movie concludes on the same beautifully ambivalent note. Like two other classics of fantasy cinema, Phil Alden Robinson’s Field of Dreams (1989) and Tim Burton’s Big Fish (2003), Watership Down ends with hope in the face of oblivion, reminding us how much fantasy is the flipside of horror, striving to achieve growth instead of despair.

Bright Eyes went on to become one of the bestselling songs of 1979, in the UK and across Europe.

Two other animated adaptations followed Rosen’s movie: a cheerful UK/Canadian cartoon series that ran for three seasons (1999-2001), aimed squarely at children, and the Netflix/BBC CGI-fest from 2018, both decidedly limp lettuce next to Rosen’s full-blooded stew.

Now sensibly upgraded to a ‘PG’ rating, Watership Down is commonly held up as a Gen-X curio, the movie that launched a thousand childhood nightmares. But its achievements as a work of dramatic fantasy are what truly resonate. Though it may lack the mythic sprawl of its source-novel, Watership Down packs a clawing excitement, emotional wallop and feral weirdness all of its own.

Stay weird.

Long unavailable to buy or stream, Watership Down has been newly restored and released in 4K by the British Film Institute, available in Limited Edition UHD and Blu-ray formats on 25th November.

Each contains identical special features, including both new and vintage audio commentaries, a host of featurettes breaking down every aspect of the movie’s production, and an 80-page perfect bound book of critical essays.

Available for pre-order from the BFI shop in UHD and Blu-ray.

Review copy provided by the British Film Institute.

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

Adams became close friends with both Campbell and Ursula K. Le Guin.

Michael Sporn Animation, sourced via an essay by Jez Stewart, Curator of Animation at the BFI National Archive, included in the exhaustive booklet of essays that accompanies the BFI’s re-release of Watership Down, available in UHD and Blu-ray.

Watership Down is a real place, just south of Newbury, Berkshire, where Adams grew up.

In his 1990 autobiography The Day Gone By, Adams reveals that Hazel was based on Adams’s self-effacingly courageous C.O. Major John Gifford and Bigwig on Captain Desmond ‘Paddy’ Kavanagh, who died in action. The seagull Kehaar was based on a Norwegian Resistance fighter named Johansen.

I recently saw the cartoon adaptation of another Adams book, THE PLAGUE DOGS, which is even more grim.

This film broke my heart as a kid. It’s nice to see people posting something a little bit different on here. 💛