How 'Dungeons & Dragons: Honour Among Thieves' Rolls a 20 for Storytelling

A milestone in fantasy cinema that illustrates exactly why writing about magic requires a true sorcerer’s touch (contains very mild spoilers)

There’s a scene in Dungeons & Dragons: Honour Among Thieves that says the movie knows exactly what it’s doing. Our party of roguish adventurers are drowning their sorrows in the local tavern, bickering over the best way to break into the bad guy’s vault. The barbarian (Michelle Rodriguez) grunts over her ale. “Can’t you just magic us inside?” The party’s timid sorcerer (Justice Smith) bristles at this. “Everyone thinks you can solve everything with magic, but you can’t! There’s rules!”

Director-screenwriters Jonathan Goldstein and John Francis Daley, along with co-writer Michael Gilio (as well as the writer of this previous essay Too Much Magic: The Pitfalls of Writing Fantasy)1, understand that nothing breaks the spell of drama more completely than characters waving a magic wand at a story problem. It’s one of several reasons why Honour Among Thieves works so well. It has a geek’s understanding of the rules of the game, but a dramatist’s flair for storytelling. In other words, the movie plays like it’s being run by a really good DM2.

The movie is another milestone in the wave of big-budget on-screen fantasy that’s been rolling for the last twenty years, ever since Peter Jackson’s still-magnificent Lord of the Rings trilogy and Warner Brothers’ charming-but-very-much-less-than-magnificent Harry Potter series. These blockbuster successes, along with advances in digital special effects and the rise of the internet, helped carry the fantasy genre out of the ghettos of fandom and into mainstream culture3.

Created by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss from the bestselling-but-not-terribly-well-known-at-the-time fantasy novels by George R.R. Martin, the first series of Game of Thrones arrived in 2011 and had clearly learned much from Jackson’s trilogy. The show treated its source material with respect, playing like dour historical drama, not some jokey fairy tale ‘fantasy’. But Game of Thrones went a step further than Jackson’s movies by humanising the classic mythic archetypes of the genre (the princess, the knight, the barbarian; even dragons became something regular viewers could take seriously. Now they were essentially big scaly nuclear weapons). Viewers who came for the tits and gore, stayed for the ruthless plot-twists and sweeping emotional drama.

Game of Thrones concluded in 2019 after eight seasons and with a bafflingly lacklustre finale, and on-screen fantasy feels like it’s been treading water ever since. With multi-season television now firmly established as a sensible home for any sprawling fantasy chronicle, the genre has lately been resorting to prequels like House of the Dragon and The Rings of Power, or series based on original but less innovative sources like The Witcher and The Wheel of Time.

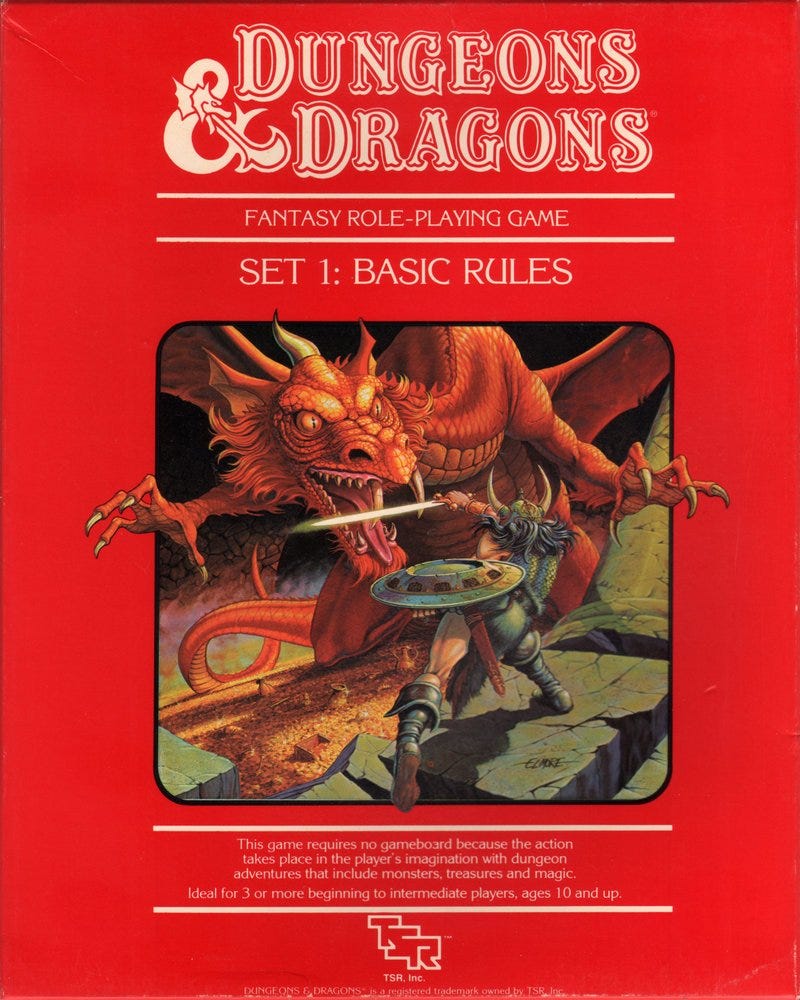

That’s why it’s so refreshing to find Dungeons & Dragons: Honour Among Thieves to be as fleet-footed and perfectly balanced as a rogue stealing across a rooftop, jazzed by its own breezy storytelling, accessible, likeable and flat-out entertaining. It also hits the zeitgeist with perfect timing, arriving amid the continued viral popularity of RPG streaming show Critical Role and the hip D&D-infused nostalgia of Stranger Things4. Nor does the movie have any previous instalment baggage to deal with beyond the best-forgotten 2000 adaptation directed by Courtney Solomon5. Of course, the movie’s designed to set up yet another elephantine franchise, but it certainly doesn’t feel like it. Nor does it require the audience to have a PhD in the source material. As the movie’s tagline cleverly puts it, ‘No experience necessary.’

Wisely building this geeky adventure upon a plot recognisable to anyone, Honour Among Thieves is a heist movie. Imagine The Italian Job with dragons instead of Mini Coopers, Ocean’s Eleven with lava-brimming dungeons in lieu of Las Vegas. The Danny Ocean of this caper is Chris Pine, weathered and leathered, but full of blue-eyed charm as a burglar-bard who took that one job too many. Now he finds himself languishing in gaol with his scowling barbarian buddy Michelle Rodriguez. Our bard is keen to retrieve a magical tablet that will resurrect his dead wife, but also needs to rescue his estranged daughter from the clutches of a treacherous former crewmate turned overlord of the city of Neverwinter (Hugh Grant, silver-haired, silver-tongued, and bringing more than a whiff of Prime Ministerial shiftiness to this bumbling conman turned Caesar. “I don’t want to watch you die. That’s why I’m going to leave the room.”)

Having recruited a fledgling wizard (Justice Smith), a shapeshifting Tiefling druid (Sophia Lillis6), and a wonderfully swoonsome paladin (Bridgerton heart-throb Regé-Jean Page), we’re off to rob the bad guy’s vaults. There’s a side-quest for a magic helm that takes in a Python-esque graveyard routine, a podgy red dragon, and one hell of a swordfight. The movie does lose a bit of focus with the even-more treacherous involvement of a cabal of crimson-cloaked eggheads known as the Red Wizards (led by arch-sorceress Daisy Head, daughter of Anthony. Yes, him off Buffy). I can’t quite remember why they want to kill everyone with a soul-draining cloud of smoke. I suppose it’s just the sort of thing that bad guys like doing.

Otherwise, Dungeons & Dragons: Honour Among Thieves ploughs through its 134-minute runtime like dragon-fire through an infantry unit. The set pieces are deft and clever, the ensemble cast likeable and fun, and the fight scenes inventive and wicked-fast. Connoisseurs of the work of Mister John Wick will find much to love in the scene where Michelle Rodriguez opens up a flagon of whup-ass on a chamber full of unsuspecting captors. But what makes the movie work as a whole is its understanding that magic requires careful handling.

Goldstein, Daley and Gilio’s script arranges the world of Honour Among Thieves as meticulously as any Player’s Handbook. We understand the rules of any given magic, its limits within this world, what can and can’t be done in any given scene. An enchanted trinket may allow a character to speak to the dead, but they may only ask five questions. A staff may cast portals that allow characters to step from one space to another, but it can’t cast a portal somewhere the character can’t see.

Compare this to the chaotic setting of the Harry Potter chronicles, in which everyone seems capable of doing pretty much anything they want, resulting in a world that’s way less coherent. Wizards can teleport, but still deliver letters via owl for some reason. Time travel’s a thing, but divination kinda isn’t. It all feels a bit slapdash. The world of Honour Among Thieves, on the other hand, takes the time to underpin its adventure with a firm dramatic structure. Feats of magic - however wild and crazy - are anchored by the laws of cause and effect. The writers place cunning limits on those enchanted artefacts, leaving the characters to resort to their own roguish ingenuity to get the job done and resolve the scene. Unlike in Harry Potter, it’s the characters who are turning the plot here, not the magic they wield.

There are rules, indeed. Perhaps too many. Fussing over strictures can make a fantasy story feel too regimented and mechanical, its magic essentially a quotidian science. Joe Abercrombie’s heroic fantasy novels make magic feel present yet unknowable, a tantalising, malevolent force in which casters dabble at their peril. At the other end of the spectrum are the novels of Brandon Sanderson, which tackle magic the way an accountant tackles corporate tax returns, a place for everything and everything in its place.

For the most part Dungeons & Dragons: Honour Among Thieves binds the forces of magic within artefacts, weapons and spells fired from a caster’s fingertips. Its magic feels more contained, less pervasive, less – well – magical. Magic here feels less a part of the fabric of the universe than it does in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth or Martin’s Westeros. In the source RPG, Player Characters select magic items from a list. Everything’s there, accounted for, every effect listed. It feels like you’re ordering off Amazon. It’s fine, but this catalogue approach does force the writer of fantasy to sacrifice that crucial sense of mystery, of lingering resonance, that liminal space where real magic resides.

But at least the world of the movie feels lived in. We see Axe Beaks shepherded through the corn fields on their way to market, Rust Monsters squabbling over some metallic morsel on the steps of a dungeon. The movie knows a major component of world-building - of storytelling itself - is showing that world getting on with itself without telling you precisely what’s going on. The inner workings are there, functioning beneath the surface, unexplained, welcoming the viewer’s imagination to step in and fill the blanks while the movie gets on with the story.

I played D&D on only a few occasions as a kid. As a Brit, my go-to RPGs were Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone’s Fighting Fantasy gamebooks (the first few of which borrowed heavily from D&D), Games Workshop’s Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay7 and Dave Morris and Oliver Johnson’s Dragon Warriors. The very British worlds these systems evoked always felt different, weirder, darker, heavier than anything in D&D. It wasn’t until I was older that I realised worlds like those of Warhammer drew as much from Kafka, Conrad and Milton as they did from Tolkien, Moorcock and Harryhausen movies. ‘Clean’ was the word we always used to describe American fantasy like D&D and the world of Honour Among Thieves looks just as sanitised, more like a theme park or a Renaissance Fair than the eerie mythic realms of Jackson’s Lord of the Rings or the medieval slums of Game of Thrones.

Those British fantasy worlds I inhabited as a teenage roleplayer had a very novelistic sense of identity. Their aesthetic was gothic and punky, full of grunge and folk horror, cynical and aggressive. But their distinctness also made them more of a closed book, harder for normies to penetrate, which is probably why we liked them so much. D&D’s blandness is what makes it so accessible. It’s a role-playing game after all and currently the most popular in the world. It’s designed to be open and inviting, to encourage players to make up scenes - even rules - on the fly, which is harder to do when your fantasy world already has a very clear idea of itself. Unless the players are incredibly familiar with the layout of that world, they often find themselves bumping into the furniture.

Playing any role-playing game is essentially improv. It’s why the seasoned voice actors of Critical Role have made such a success of the show. D&D sessions work best when referees and players apply ‘yes and’ to a given situation, accepting a prompt and elaborating further as they move the story along. One of the most memorable moments in Honour Among Thieves has the shapeshifting Tiefling transforming into a sequence of different animals as she scurries, squirms and buzzes through the villain’s lair, guards pouncing on her from every angle. Capture, escape, capture, escape, it’s a truly bravura sequence breathlessly inventive and all captured in a single take!

The movie’s characters are just like role-players, like Indiana Jones: making it up as they go along. They’re as clueless as we’d be in a situation as desperate as theirs, which is the reason we like them so much. Dungeons & Dragons: Honour Among Thieves doesn’t drown the viewer in backstory or drift away on a cloud of self-importance. Instead, it welcomes us like a guest and invites us to play.

At the time of writing, Honour Among Thieves has scored a “solid” $15.3m on its opening day, according to Variety, and is projected to finish the weekend at $40m. Reviews have been overwhelmingly positive, although many of the D&D YouTubers I follow have been a little more reserved. Understandably so, given a recent seismic controversy. Back in January, D&D’s current owners, Seattle-based Hasbro subsidiary Wizards of the Coast, threatened to revoke their ‘Open Gaming License’, which allows independent creators to write and sell D&D spin-off material. Fans and creators took up arms and Wizards of the Coast - with the release of Honour Among Thieves just around the corner - went into full retreat.

Many D&D players feel their love for the game - and anything to do with it - has been soured by the experience. It remains to be seen whether Honour Among Thieves will salve corporate wounds by finding a new and wider audience. It also remains to be seen just how digitised D&D’s future will become, with many players fearing its forthcoming sixth edition, One D&D, will skew heavily towards virtual tabletops and micro-transactions. WotC insist any such trampling of the game’s legacy will never happen, although it appears someone forgot to add the names of D&D’s original creators Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson to the movie credits.

Your Next Read…

POSTCARDS FROM THE EDGE OF SOMEWHERE: Q&A WITH FANTASY AUTHOR JOHN FRENCH The award-winning author, scriptwriter and games designer talks craft, getting published and staying focused, as well as revealing his new creator-owned fantasy project 'Letters from an Unknown Land'

TOO MUCH MAGIC: AVOIDING THE PITFALLS OF WRITING FANTASY Anything can happen in a fantasy story. So how can writers prevent theirs from spiralling out of control?

SWORDS, SORCERY AND THE SHE-WOLF In the age of corporate epic fantasy has pulp-era sword and sorcery become more appealing than ever? Wondering where the genre stands as I discover a forgotten fantasy heroine from the Marvel vaults.

Dude also wrote a really good book on fantasy movies, Empires of the Imagination: A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema from Georges Melies to The Lord of the Rings (McFarland, 2005).

That’s ‘Dungeon Master’ for those of you unfamiliar with the venerable game from which this is adapted, and which you’ve probably seen the kids on Stranger Things getting excited about. See, Dungeons & Dragons is a tabletop role-playing game (or ‘TTRPG’ or just ‘RPG’) in which one player takes the role of the DM, a kind of narrative overlord or referee, while the other players take the role of PCs (Player Characters), who can be anything from a human ranger to a dwarf blacksmith, each with their own special abilities and personality quirks. The DM comes up with the overall premise and story beats (but don’t worry, there’s pre-written adventures out there that can do all the heavy-lifting for you). Maybe the PCs need to rescue a kidnapped nobleman, steal a treasure or slay a dragon. The DM sets each scene in which the players make their decisions. (“Okay, guys. You step cautiously into a darkened chamber with an open treasure chest facing you from the opposite wall. A dead body lies between you and the chest, covered in tiny feathered darts. What do you do…?”) The players take this in and figure out a course of action, rolling dice to determine whether or not those actions are successful, or – better yet – result in a catastrophic fail that will land them in even more trouble. Role-playing games are a unique form of collective storytelling that offers a breadth of expression and creativity unrivalled by any video game. It’s immersive, fun, spontaneous and it’s not just for people who like fantasy. There’s RPGs that offer the chance to play as a Jedi, a vampire, a hard-boiled femme fatale, an undead pirate, a single man in possession of a good fortune who must be in want of a wife… The imagination’s the limit.

As a lifelong fantasy devotee now in his late forties, I must confess to feeling occasionally bewildered by fantasy’s current popularity. When I was a teen in the late eighties this stuff wasn’t just uncool, it was toxic! It was the love that dare not speak its name. You didn’t tell anyone beyond your closest friends that you were into this stuff, not if you wanted to keep your teeth at break-time. Fantasy was the genre of the social pariah. Now we have hipsters and hot people playing D&D to an audience of millions! How the hell did that happen? I can’t help but feel there’s an unacknowledged generational component behind a lot of the angry gatekeeping that goes on in the various sub-fandoms of the fantastic. Not to excuse any form of bullying or harassment, just to acknowledge that there may be older fans out there who went through a lot of shit for their love of the genre back in the day. Here’s hoping they heal up and move on.

Does anyone out there know how Stranger Things can use D&D and its characters in the show? Did Wizards of the Coast pay for a product placement or does it somehow come under fair use? Lemme know in the comments…

Despite the fact that Solomon’s Dungeons & Dragons is inarguably one of the worst fantasy movies ever made, license-holders Wizards of the Coast saw fit to put the D&D brand on two made-for-TV sequels: Wrath of the Dragon God (Gerry Lively, 2005) and The Book of Vile Darkness (Lively, 2012). Reviews were not kind.

Yes, we all know she shouldn’t be able to wildshape into an owlbear, but just go with it, okay?

Designed and written by Richard Halliwell, Rick Priestley, Graeme Davis, Jim Bambra and Phil Gallagher.

Thanks for the review and your thoughts on fantasy writing. I must admit, I had no interest in this film. The first I knew about was seeing a trailer last month. The trailer was basically the actors talking about their characters, but showed little of the film. This made me think "is your film so bad that you refuse to show it in the trailer?" But yours is the second positive review I've received this week, so I might check it out now. Cheers