Fantastic Beasts and How to Write Them

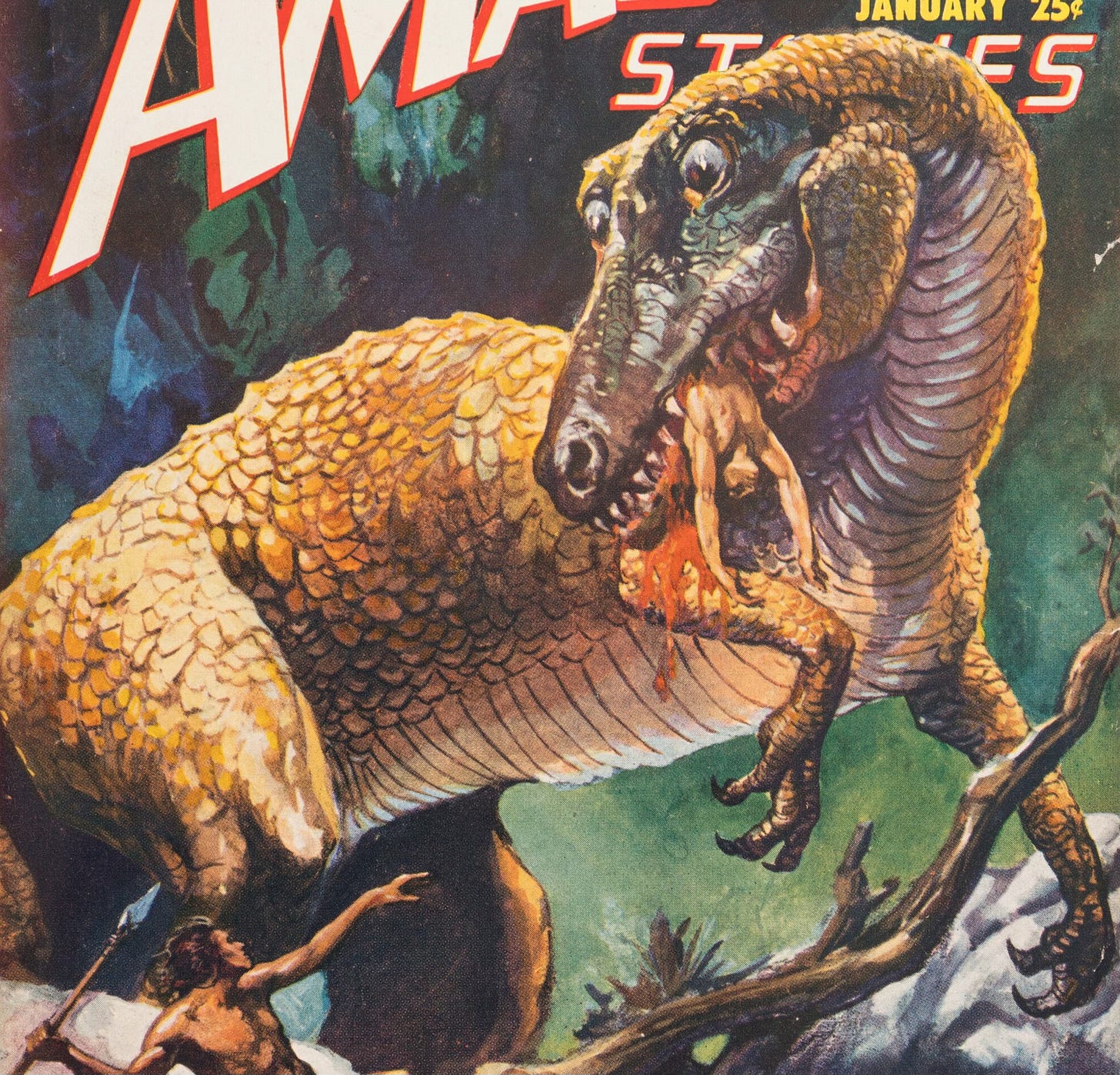

Some Jurassic examples of great monster-writing

Upon reaching the limits of civilised knowledge, the mapmakers of yore would resort to monsters. Hic Sunt Dracones – Here Be Dragons. In truth, cartographers almost never wrote this1, but there’s a reason the phrase has endured.

It conjures images of fabulous beasts prowli…