How We Built Black Beth

Resurrecting a British sword and sorcery heroine and what it takes to write a character 'well'

How do you know when you’ve written a character well? When the reviews tell you? When the fans are satisfied you’ve honoured the complex rituals of continuity? When the bank informs you your invoice has gone through?

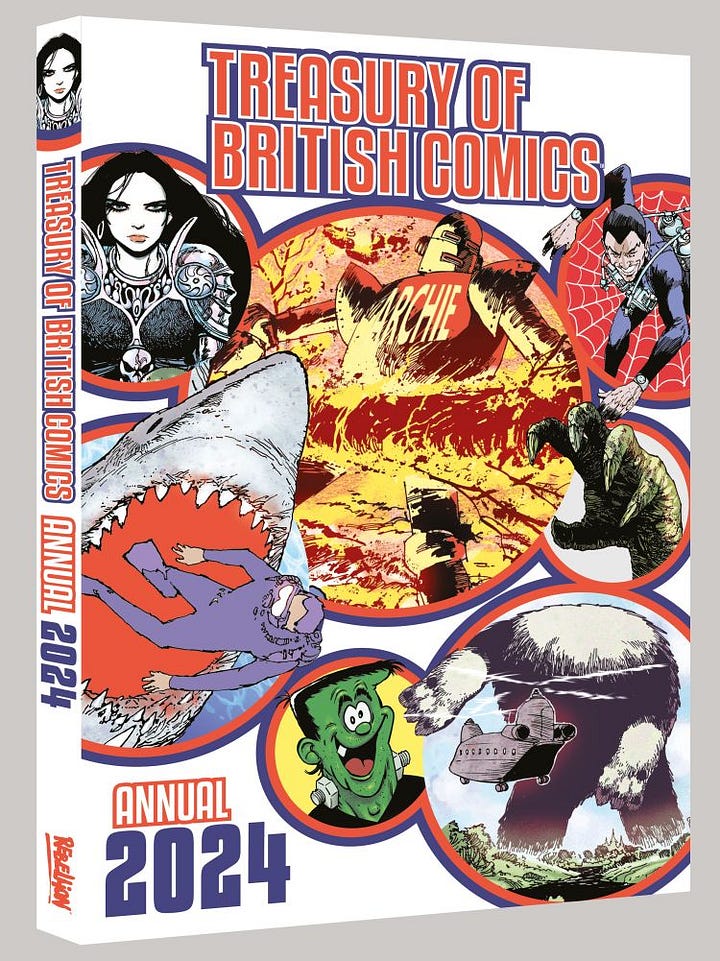

Artist Dani and I have got another Black Beth story out this week, a wintery sword and sorcery tale entitled Death Carries Roses, anthologised in the hardcover Treasury of British Comics Annual 2024.

Our vengeful sword-maiden and her blind sidekick Quido feature alongside vintage works by legends including Brian Bolland, Dave Gibbons and Steve Dillon, as well as familiar characters such as The Leopard from Lime Street and The Spider1. The character having languished in obscurity for decades, Beth’s appearance in this line-up certainly feels like she’s visible once again, accepted into the pantheon of British comics characters.

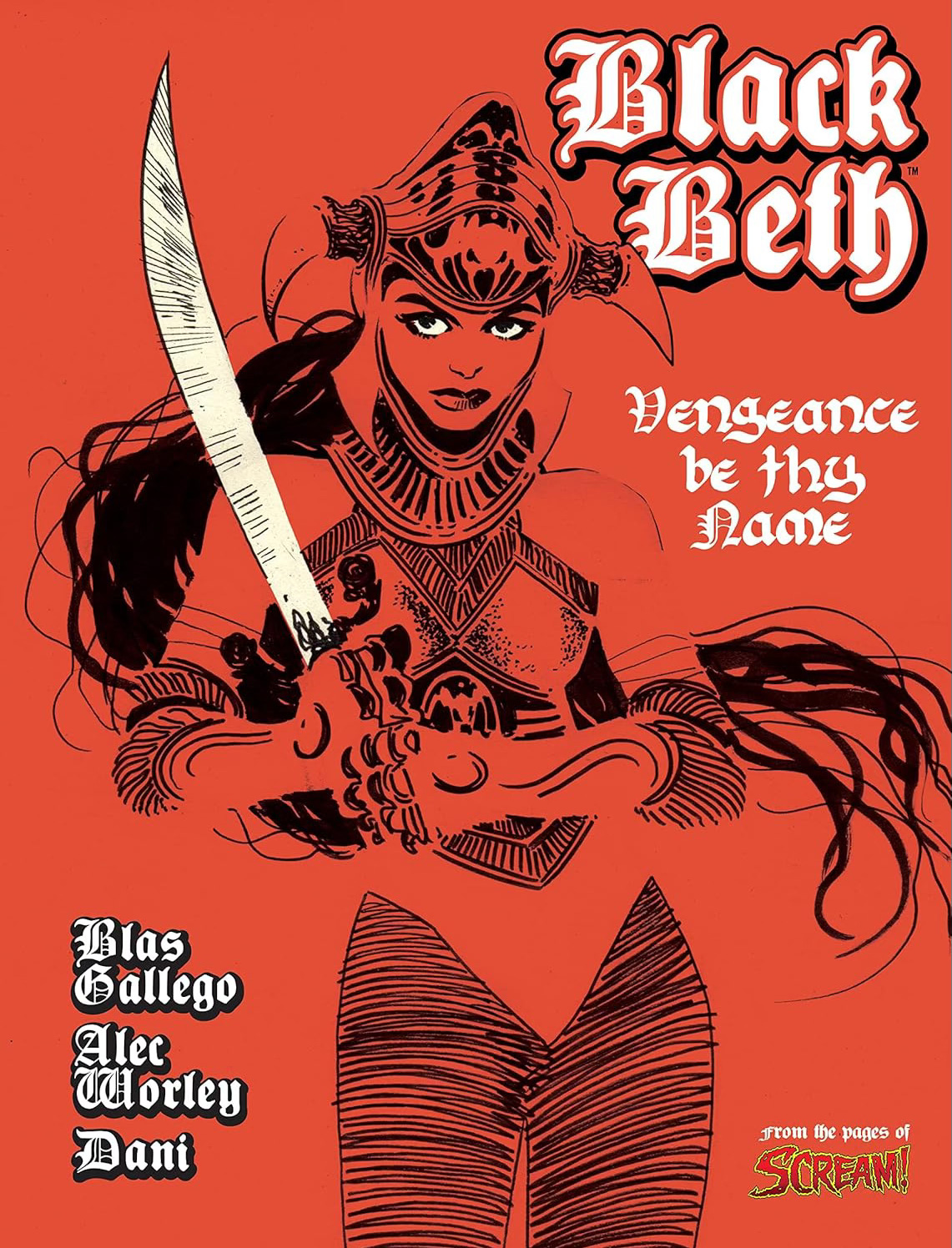

It feels good to know that all the hard work we’ve done on Beth hasn’t been for nothing. We managed to get her trade collection, Vengeance Be Thy Name, under the noses of a bunch of reviewers, whose feedback was almost unanimously glowing. But let’s be honest. Reviews are there to convince other people, not creators.

Creators harvest review quotes to sell their books to potential readers and themselves to potential commissioning editors. Beguiling as good reviews are, creators who look to them for artistic validation risk stepping from the path and drowning in the mire.

To forget those outer voices and give yourself over to a character, to feel them becoming lithe and noisy inside your head, is a good sign that you’re writing them well. Nothing else has a chance of happening – not sales, not word of mouth, not recognition, not good reviews – until that character feels like they’re alive.

I’m at the stage with Black Beth where if I suggest throwing her into a certain adventure, she’ll ‘tell’ me how she’ll react. The best play here, then, is to kick her into situations that will properly test her, force her into making choices that will dramatise her (fairly crazed) personality. In the first short story Dani and I created for her, Magos of Malice, Beth must save a group of sacrifices from a warlock intent upon unleashing an unspeakable evil upon the world. But Beth’s enigmatic ally Moldred the Cinder-Witch has warned her that to undertake this mission will have terrible consequences. Will Beth heed Moldred’s advice? Or is her vendetta against evil-doers all that matters to her? The choice Beth makes reveals who she is and the extremes to which she’s willing to go.

I used to fret about not knowing where a character is heading from story to story. What if I couldn’t come up with an idea for their next adventure? Then I learned to listen to the rhythms of their accumulated sagas. If you went big with the last story, go small with the next. If the last one was set in desert, set this one in the snow. Having had Beth save an entire city from being drowned by a Godzilla-sized rock golem in her previous adventure, The Devils of Al-Kadesh, I figured we should next do something more psychological. So, in Death Carries Roses, we’ve gone smaller scale, focusing on Beth’s reluctant pact with her sinister mission-giver, Moldred.

I should stress that a creator being given license to follow their whims like this is a luxury rarely afforded in comics2. It helps that Black Beth was a strip so long forgotten that it came with zero baggage or fan expectation, but kudos to Rebellion – and specifically my editor Keith Richardson – for giving me the freedom to build the character the way I felt worked best – worked best not for me but for her. Dare I say, it now feels like we may have established Black Beth as the UK’s grimdark answer to Red Sonja.

The strip’s re-emergence certainly chimes with the current rekindling of interest in pulp sword and sorcery. Follow-ups to quasi-classic movies Hawk the Slayer and even Deathstalker (for some reason) have found their way into graphic novels, while grandaddy Conan recently found a new home with Titan Comics. Michael Moreci and Nathan Gooden’s Barbaric is busy blossoming into a full-blown comic-book franchise, and the late Kentaro Miura’s 40-volume manga Berserk remains eternally popular.

Sword and sorcery fiction anthologies have made a comeback, with titles such as Tales from the Magician’s Skull, New Edge Sword & Sorcery, and Swords in the Shadows by

all successfully Kickstarted by communities of dedicated readers.The Discord server run by amateur sword and sorcery magazine Whetstone is abuzz with conversations on how best to move the genre forward3, to convert nostalgia for the characters many of us fell in love with as teenagers into something innovative and challenging – precisely the dilemma I’ve had to negotiate in reviving not only Black Beth but Durham Red, Hook-Jaw, and several others.

READ: Swords, Sorcery and the She-Wolf In the age of corporate epic fantasy has pulp-era sword and sorcery become more appealing than ever? Wondering where the genre stands as I discover a forgotten fantasy heroine from the Marvel vaults

Right now, sword and sorcery4 feels charged with the same sense of excitement and creative potential that I first felt when I discovered the genre in the fabled 80s. I’d gaze into artwork by John Blanche or Rodney Matthews and lose myself in wonder, imagining the horrors and treasures that awaited discovery beyond that brooding horizon. Back then, the worlds of fantasy were not frequented by the cool kids. The rise of internet culture had yet to buoy the genre out of the dungeons and up into the accepted mainstream. There was no Game of Thrones, no Stranger Things, no Critical Role. Professing your love for Hobbits would have had the hard kids at your school come down on you like Ringwraiths on a hotel duvet.

Ah, fantasy. Twas the love that dare not speak its name, and my paramours were Citadel Miniatures, Fighting Fantasy gamebooks and Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay. My focus was narrow since money was tight and fantasy that my mum would let me get my hands on was tough to come by. I wanted to check out all those cool-looking barbarian movies with the Boris Vallejo sleeve art, but there was no way I was allowed to rent anything that promised such a high boob-count5.

That I hungered for fantasy content to the point of delirium is the only possible explanation I have for believing that Hawk the Slayer was one of the best movies ever made.6 I clung with a Gollum-like hunger to my tatty collection of fantasy ephemera, studying them with the fervour of an apprentice warlock studying for his exams. The ads that ran in the back pages of White Dwarf promised wondrous RPGs I’d never get to play. Movies like The Dark Crystal and Krull had me craving sequels I’d never see. That Fighting Fantasy artwork by Blanche and Iain McCaig smouldered with a weird vitality, illustrating so much more than the accompanying text.7

When a story holds back, we’ll meet it half-way, furnishing its world and characters with a significance and inner life of our own making. Thus, did Black Beth first drive her scimitar through my heart from the pages the 1988 Scream! Holiday Special.

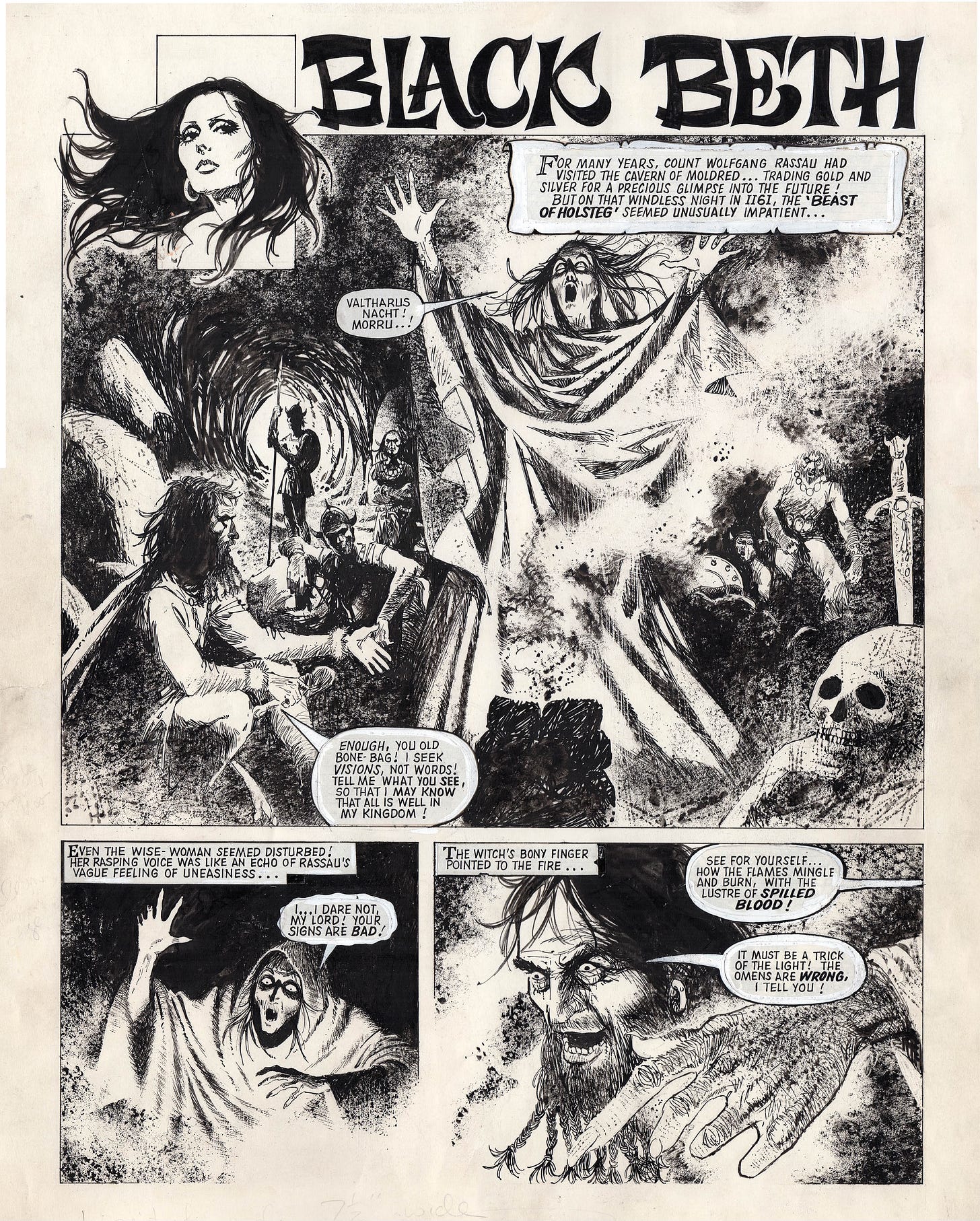

Scream! was a wonderfully inventive horror comic, which – by then – had been out of print for four years. Purchased during a drizzly summer holiday in Norfolk, this otherwise naff Holiday Special offered a few reprints, a couple of drab one-pagers and – what’s this? - a spectacular 23-page sword opera called Black Beth?

It was a delirious Euro-fusion of MacBeth and The Punisher in which the evil Count Rassau, ‘the Beast of Holsteg’, learns of a prophecy that he shall one day be destroyed by an armoured woman on horseback named Beth, “…a thing of vengeance! ‘Tis coming for us!”

Keen to re-establish his authority, Rassau throws his weight around among the quailing peasantry, chancing upon a harmless raven-haired maiden named Beth on her wedding day. Not taking any chances, Rassau orders the entire village burned to the ground (as happens in the first reel of every ‘80s barbarian movie ever, from Conan the Barbarian to Ator the Fighting Eagle).

The wilting Beth is scooped from the wreckage by an eyeless hunchback named Quido, Rassau’s ex-henchman, blinded for refusing to obey orders. Cue the training montage and Beth is reborn a Valkyrie-like death-machine…

Having fulfilled the very prophecy he sought to avoid, the villain thus meets his well-deserved doom.

The artwork had the same smoky, sinuous quality as Bob Harvey’s illustrations for the Fighting Fantasy book Talisman of Death and the Dragon Warriors RPG. What the heck was this doing in a horror comic? Where had it come from? What happened next? Black Beth was both spectacle and mystery.

Nearly thirty years later, 2000 AD publishers Rebellion acquired the majority of a vast comic book catalogue previously belonging to British publishing giant IPC. And that included the rights to Scream!. When I read the news, it dawned on me that they might have the rights to Black Beth. To think that I might have a chance of creating a sequel or even a full-on reboot swept me back to those long-lost days of high adventure.

But characters cannot live on nostalgia alone. Rely too much on reminiscence and you risk losing both your readers and yourself in a fog of your own whimsy. Like the lotus eaters of Greek myth, the dreamer becomes lost in the dream. Our very greatest fantasy stories never succumb to their own escapism, but remain anchored in social or psychological reality. They help us confront our own neuroses, our traumas and experience through the symbolic language of the imagination. It’s through her trip to Oz that Dorothy learns to live in Kansas.

So blind love for a character will only get you so far in writing them. To write them well you also need to be fascinated by them in some way. At the very least, you need to find something in them, some theme or aspect to which you can relate.

In his 2009 blog post You'd Better Be In There Somewhere, veteran comic book writer Mark Waid recalls how he once struggled to find an ‘in’ on a 2001 Crossgen book called Sigil. The writer simply couldn’t relate to the main character Sam…

“Finding my ‘in’ was extra-challenging – but that’s the job. If you’re going to write a character convincingly, you have to find something in him, however small, that resonates with you.

“After much studying and much drinking, I hit upon the one commonality Sam and I had: we were both vagabonds with no family ties. I got that, and something clicked. That suggested that there was some backstory with his parents. That there might be a reason he felt estranged from friends and family. That there might be some nugget of masked insecurity inside him that made him feel uncomfortable with close relationships. THAT, I got.”

Thor was another character whose universal appeal had stumped Waid for years.

“I never got Thor. I have absolutely no interest in mythology, Thor’s trademark “thee-thou-thine” faux-Medieval dialogue feels corny to me, and Thor is traditionally about as bright as a week-old glowstick. And yet… and yet… he’s been one of comics’ mainstay heroes for nearly a half-century, which means there had to be something in the concept that the audience can identify with. I just couldn’t find it. And, worse, a few years back when I was doing a handful of Marvel books, I had to write Thor from time to time.

“So I finally broke it down, and once I did, it was embarrassingly obvious: Thor is about a rebellious son who can’t please his father no matter what he does. Odin’s a jerk. He claims to have a very clear vision of Thor’s destiny, one that doesn’t involve wasting time with Earthlings, but like many fathers, he’s much better at articulating what Thor isn’t supposed to do than what he is supposed to do. There’s poor Thor, just trying to follow his heart, while Odin – time and again with all the compassion of a hurricane – punishes Thor for breaking specious rules that were never very clear to begin with.

“THAT, I got. THAT, hundreds of thousands of teenage readers have been getting since 1962.”

Having got the green light to pitch a brand-new Black Beth story – almost thirty years after her last appearance – I knew that she would have to appeal to more people than just me.

As Waid puts it… “Characters, if they’re to have any longevity, have to speak to universal concerns.”

Finding that universality is part of a writer’s due diligence in approaching any character. You have to figure out who they are, what they’re about, and – crucially – what they mean. Digging up Beth’s backstory, however, turned up an unexpected abundance of treasure.

Digging into such resources as Hibernia Comics’ It’s Ghastly! The Untimely Demise of Scream! and reaching out to Scream!’s original editor Barrie Tomlinson, as well as artist and comics historian David Roach, and editors Dez Skinn and

, I learned that Beth’s origins reached back over ten years before her first appearance in 1988. It turned out the strip had been created in 1976 for another IPC title (also called Scream).But the comic got canned before issue one saw print and Black Beth’s pages were left in a drawer in the IPC offices for over a decade. They were exhumed in 1988 by editors looking for material to fill up that Holiday Special, after which poor Beth went into hibernation once again.8

Her original creators went uncredited, though the artist was veteran Spanish illustrator Blas Gallego (link NSFW). Famed for his Conan covers and erotic comics9, Gallego was especially prolific in British magazines in the 1970s, drawing for several teen and women’s titles, as well as Dez Skinn’s House of Hammer. But who was Beth’s original writer?

Original Scream! editor Barrie Tomlinson told me that IPC used to keep ledgers listing every contributor of every issue of every comic. Unfortunately, some overzealous member of staff decided to have a clear-out and those precious catalogues ended up in the bin.

Issue #15 of Paul Duncan’s fanzine ArkenSword (September, 1985) threw up an interesting titbit in an interview with artist and Halo Jones co-creator Ian Gibson. “IPC were intending to do a dummy with some fantasy female character,” said Gibson. “IPC rejected my pages, but I ended up doing the job anonymously with Blas Gallego. The story ended up being called Black Beth.”

I contacted Mr Gibson myself and he confirmed that he had indeed assisted on the pencils. He suspected that Gallego himself may done the scripting, but he told me himself that he had no memory of ever doing so.

As David Roach put it, “If Ian says Blas wrote it then that's as good a lead as we're ever going to get.”

By the time I’ve compiled my research and (hopefully) worked myself up into a frenzy of enthusiasm, I always take a step back. It’s crucial not to lose your cooler editorial head, especially when working on a character you remember so fondly or in which you have a deep emotional investment. Identify what it is about this character that so appealed to you in the first place. It would be easy to scatter easter eggs and let the reader play ‘Spot the Homage’, but that’s not world-building; it’s game-playing. I want the reader absorbed in the scene I’m putting in front of them, not thinking back every five minutes at somewhere they’ve been before.

When Steven Spielberg made Raiders of the Lost Ark, he didn’t signpost every movie that influenced him, from Secret of the Incas to Zorro’s Fighting Legion.10 Instead, he worked to evoke their feeling of boundless adventure in which dashing adventurers face nail-biting perils in the remotest corners of the world.

I wanted Black Beth to evoke that feeling I had as a kid watching Jason and the Argonauts or Golden Voyage of Sinbad, absorbed in that woozy, sun-baked world of mysterious islands and crumbling colossi, of drawn blades and devilry, where heroes brave arcane sorcery armed with little but courage and cunning.

Partially inspired by the OSR (Old School Revival) movement currently enjoying its own renaissance in tabletop RPGs, I wanted to bring modern storytelling to that bygone world, to maintain that sense of wonder, but with some thematic depth, to invite the reader’s imagination, rather than doing all their imagining for them.

If Agent of Weird got you smiling, thinking, or ready to create, then please consider sharing, subscribing or throwing me a healing potion. Every drop of reader-support will help this project grow.

My only really conscious homage was to Beth’s Spanish creator Blas Gallago. It felt like a much-deserved tribute to make this world feel something like medieval Spain, with a heavy Moorish flavour: walled cities and minarets and water-gardens and bazaars and thieves’ alleys and - beyond - a world of ghoul-haunted plains and high adventure. I gave Dani tons of reference of Almería in southeast Spain where they filmed the original Conan and all those Spaghetti Westerns.

By stopping to ‘listen’ to the story, I felt it telling me it wanted to be a full-on fantasy rather than the medieval sword opera of that original strip (which is specifically set in 1161 and name-checks the Norse god Odin). So our Black Beth ended up as not a continuation of her debut, but more a subtle reinvention. Again, I must point out that having the creative freedom to play with a company-owned property in this way is a rare honour indeed.

Given the opportunity to work on a cherished character, many writers, I feel, make the mistake of disregarding the reader, or worse still of treating the readership like an adversary in need of rehabilitation or mockery. As

puts it in this excellent piece…“Art isn’t osmosis. There’s no way to force everyone to absorb your intended message. It’s simply not how things work. But beyond the impossibility of that task, we should think about what gets lost when we focus on appeasing dullards. If we are so concerned about what might confuse our worst readers, what is left for our best readers? If all art must be blunt, what about readers who desire subtlety? If our stories are simplistic, what about people who enjoy complexity? Do we really want all our art to be flat, formulaic, and dulled of any edge? Focusing on not confusing our worst readers ensures that we bore our best ones.”

To write a character well you need a clear conception of that best reader. But “comics are everyone”. Yes, of course, comics as a medium should never feel like a fortress, but an open forum in which all are welcome to contribute and share and enjoy our vast store of tales, regardless of background, wealth, ethnicity, faith or self-identity, nourishing and challenging each other with the staggering diversity of our lived experiences.

But not all comics are for everyone.

Dogman and Multiple Personality Detective Psycho are both comics, but those books are for completely different readerships and market demographics.

I wanted Black Beth to appeal to a wider, younger audience than the handful of old farts who might have remembered this character from the ‘80s. Again, I did my research and figured something like Beth might appeal to the same readers who like nuanced badass fantasy novels like Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows or Sarah J. Maas’s Throne of Glass.

I made Beth younger and less sexualised than the slinky siren of Gallego’s original pages. Dani and I based her on Black Sunday-era Barbara Steele and our Quido on Hunger Games hottie Liam Hemsworth, tweaking the characters’ relationship to give them plenty of dramatic mileage. (And dispensing with the slightly kinky mistress-servant vibe they had in the original.)

I’ve no idea if I’ve succeeded in actually reaching this target readership. Most of the time, I feel like me, the artist and editor are probably the only people even caring to make the distinction. That said, the trade collection has been in the top thirty bestselling Fairy Tales, Folklore, Legends & Mythology Comics & Graphic Novels for Young Adults on Amazon ever since the book came out. Does that mean anything? God knows.

I feel I’ve done right by Black Beth. I’ve honoured her past, put her back on her horse and sent her galloping towards the audience who would best appreciate her. I’ve given her all my love and yet she’ll never be mine. She’s company property. And that’s the eternal tragedy of the work-for-hire writer. You have to care. It’s really the only way to do the work properly. You have to lavish love and attention onto a character until that awful sense of ownership starts creeping in. I know I’m doing a good job when I start feeling like I could murder anyone who comes between me and ‘my’ characters, when I’m doing my best to ignore the hideous truth that I could be off this project tomorrow – for any number of random reasons – and might never be with this character again. I’ll bet Gallego felt the same when he was drawing her for what would be the first and last time.

It must be so much easier to be a hack, to not give a shit and just rattle this stuff out. At least you don’t risk emotional ruin – and you’ll still get paid. Tempting. But a character cannot truly live until you’ve given them a piece of your heart.

Stay weird.

Black Beth: Vengeance Be Thy Name collects five Black Beth tales, including the original 1970s strip by Blas Gallego, three shorts - Magos of Malice, The Witch Tree and Fairy Tales - and the 48-page one-shot The Devils of Al-Kadesh by Alec Worley and DaNi, available from Amazon, the Rebellion webstore and all good comic shops.

Familiar if you’re British and of a certain age.

Certainly to low-level grunts like me.

A conversation I’ve been following on the excellent Rogues in the House podcast and The Silver Key, a blog by Brian Murphy author of Flame and Crimson: A History of Sword and Sorcery.

By my definition (which you can read about in my book Empires of the Imagination: A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema from Georges Méliès To The Lord of the Rings), sword and sorcery or ‘heroic fantasy’ differs from the broader scope of ‘epic fantasy’ as popularised by Tolkien. Sword and sorcery isn’t interested in rites of passage or restoring a wounded land. Its heroes are rude, blue-collar roughnecks like Red Sonja, Sinbad, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. The archetypal epic hero is Arthur or Frodo, committed by duty to rescue civilisation; the archetypal sword and sorcery hero just wants to get paid and laid. These guys are killers, shaggers, pirates, explorers, crude and uncouth, Herculean culture heroes battling on the frontiers of the known world. As such, the genre lends itself wonderfully to comics and short stories, so long as they’re fast, bloody, and sharper than Cimmerian steel. The founding fathers of 20th century secondary world fantasy were Tolkien and Conan creator Robert E. Howard - one English, one Texan; one an upper middle-class academic steeped in the classics, the other a dirt-poor pulpster battling the typewriter to win his next paycheck; one fascinated by the eternal symphonies of faith and myth, the other just wanting to express his wildest passions and get paid for it. And therein lies the founding difference between these two subgenres of fantasy.

I remember my first VHS viewing of Conan the Barbarian getting sternly curtailed by my mother when Arnold had that carnal altercation with the wolf-witch. “Zaaaaa-moooooooorrr-aaaaaaaaaahhhhhh!”

Planning an essay entitled, What Hawk the Slayer Got Right! Stay tuned…

The British fantasy imagery upon which I cut my teeth was by the sacred trinity of John Blanche, Ian Miller and Russ Nicholson. Their worlds were the stuff of Bosch, Kafka and Sid Vicious. By contrast, the American art you saw on the D&D books – epic though it was – always looked too clean, more like a National Trust site than a grotty medieval shithole. Plus, everyone had amazing hair.

She popped up once more as a 1989 reprint in Fleetway/Quality’s Slaine the King #21-22.

You can see in some panels of the original strip that Beth’s curves have been blacked out, suggesting that Gallego’s original artwork was spicier than IPC would have preferred.

Like the bulk of his audience would have remembered those movies anyway!

Very insightful article Alec and well-done in making Beth a success. Hopefully, we'll get more from her in the future. I like what you have done with the character and her world.

Wow!