"I Want You To Stop Me!" The Dreadful Allure of the Helpless Monster

How the tragic movie maniacs of The Black Phone and The Menu are all the more terrifying for having a hopeless method to their madness. (This piece contains mild spoilers.)

How much more frightening is the monster for whom you feel a measure of pity? This painting by the Spanish master Francisco Goya (1746-1828) will be familiar to anyone who has so much as flicked through a book on horror history in the last forty years. It was part of a series of private murals daubed on the walls of Goya’s hermitage outside Madrid, towards the end of a life that had rendered the painter deaf, embittered and traumatised by the ravenous horrors of Napoleon’s invasion. It depicts the ancient Greek Titan Cronos (known as ‘Saturn’ in Roman mythology) gnawing on the remains of his own child, driven to cannibalism by a prophecy that said his offspring would one day usurp him. Originally untitled, the painting was later canonised by art historians as Saturn Devouring His Children. Goya painted it on the wall of his dining room.

Now, look into those eyes…

There’s no triumph in that stare, no demonic glee, no ‘Bwa-ha-ha-ha!’ Those eyes are helpless. This immortal Titan is little more than an animal caught in Destiny’s trap.

Mexican maestro Guillermo Del Toro has cited this painting as a direct influence on the Pale Man he created for Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and I’m wondering if it had a similar influence on Scott Derrickson’s quietly brilliant horror movie The Black Phone (2021), scripted by Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill from a short story by Joe Hill of

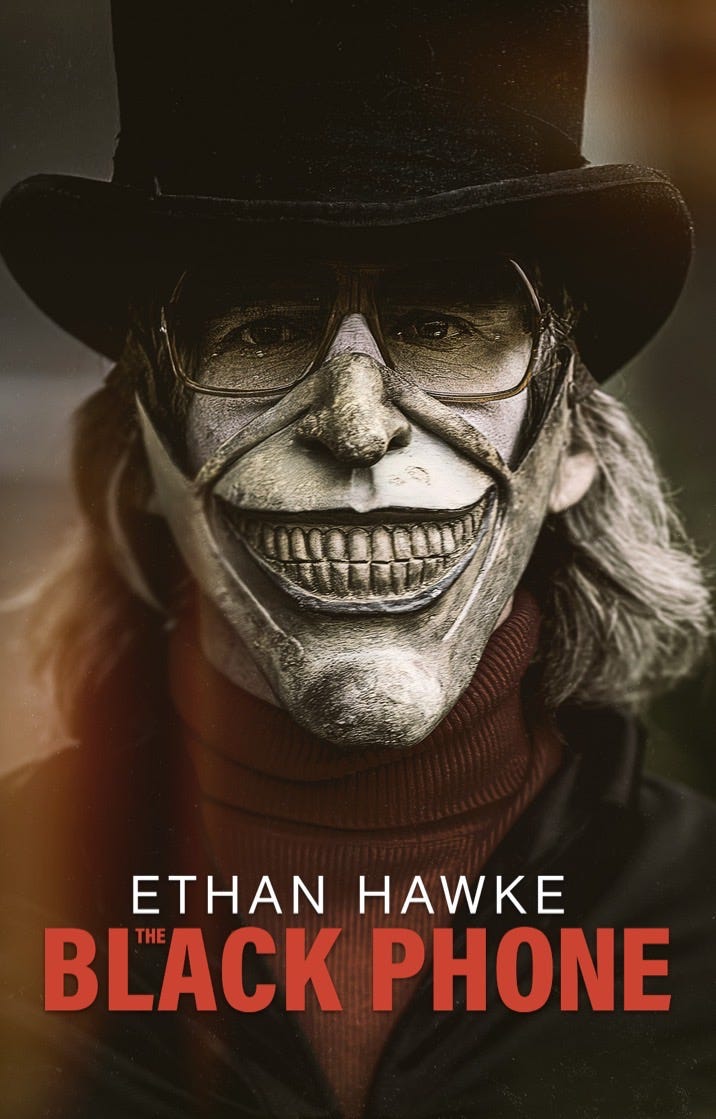

.An impressively taut supernatural thriller set in the polyester drab of ‘70s Denver, The Black Phone follows a young boy named Finney (Mason Thames) kidnapped by a neighbourhood bogeyman known as ‘the Grabber’. Played by Ethan Hawke, the Grabber lures children by posing as a top-hatted magician, a magician with a disappearing trick that involves a bunch of balloons and a grubby black minivan. He keeps his victims locked in his basement until the broken clockwork in his head ticks down to the point when his urges finally get the better of him.

The movie is at its most brutal in its depiction of childhood, here a Grimms-ian game of survival regardless of whether the kids are at school, at home, or trapped in a madman’s dungeon. What little blood gets spilled in this picture is mainly spilled between the kids themselves. Finney’s abusive father (Jeremy Davies) is another ogre, a broken alcoholic traumatised by the loss of his wife, a monster as powerless as his own child.

The Black Phone’s high-concept premise involves an old rotatory phone on the wall of the Grabber’s basement, long disconnected but through which the ghosts of previous victims relate clues that could lead to Finney’s escape. But as ingeniously as this builds in terms of plot, it’s Ethan Hawke’s protean Grabber that remains the movie’s most compelling feature. Peering out from behind a custom Kabuki-mask, whose interchangeable features range from playful smirk to ominous grimace, Hawke still manages to convey a swamp of emotions bubbling behind that graven grin. He oozes from skittery clown in one scene to silent brute the next, wringing some truly squirm-inducing moments out of lines like, “nothing bad is gonna happen here…”

The Grabber is a monster that invites the kind of frontier justice that once did for Freddy Kruger. As the movie’s stakes rise and the extent of the Grabber’s atrocities towards children become ever more apparent, the audience is stoked and fired into wanting nothing less than to see that mask split by a well-aimed round from a Police service revolver. And yet, on the rare occasions we’re allowed a close-up of the Grabber’s eyes behind the mask, those eyes are the glistening blue of a terrified child.

As The Black Phone plays its clever game of captive vs. captor, the movie skilfully infers (because Derrickson and Cargill are smart enough to know that spelling everything out for their audience will only diminish the horror) that the Grabber is acting out a cycle of abuse that he himself suffered as a child. At one point, the Grabber deliberately leaves the vault door open, testing Finney’s obedience as his captor waits upstairs, beefy and shirtless in a chair, ready to deal out a merciless punishment with a well-used belt. In casting himself as the parent and Finney as the wayward child, the Grabber is enacting his own tragedy, bound by an awful routine he’s unable to resolve.

The Black Phone is a movie about how male violence pollutes and degrades, creating a monstrous cycle. The movie’s ending is not a victory.

The Grabber comes from a long line of tragic monsters, from Doctor Frankenstein’s lumbering pile of stitches and self-pity, to Lon Chaney Jr’s hapless Wolf-Man and reluctant killer Louis de Pointe du Lac in Interview with the Vampire. (Very much looking forward to the new series with Jacob Anderson in the role.). There’s a memorably creepy line in Robert Harmon’s grindhouse classic The Hitcher (1986) where C. Thomas Howell makes an ill-advised roadside pickup in the form of sweating, goggle-eyed maniac Rutger Hauer. Forced to drive with a knife pressed up under his eyeball, Howell sobs, “What do you want?”

Rutger breathes back…

Mark Mylod’s deliciously Grand Guignol The Menu (2022), written by Seth Reiss and Will Tracy, features yet another monster who would rather not be doing the awful things he’s doing. Ralph Feinnes plays imperious chef Julian Slowik, who invites connoisseurs to a private island to savour a menu that might possibly earn him some robust feedback on Tripadviser – should any of his guests actually survive. The evening spirals into a wonderfully satirical absurdity that’s like an evil Ratatouille - Saw with a Michelin Star.

Chef Slowick is a villain of ego, his pathology too complex and rarified to provoke the primal terror of a Fairy Tale child-catcher like the one in The Black Phone. But both these monsters are trying to fix what’s broken inside them, a curative that will unfortunately cost the lives of several others.

Much of why The Black Phone and The Menu work so well is because they provide method to the madness of their monsters. There’s a pathology at work that informs the villains’ decisions and drives the action of the story. Theirs is not evil for evil’s sake, the kind of randomness that murders drama as surely as a ball-peen hammer to the cranium. Even Heath Ledger’s Joker, for all his seemingly arbitrary crimes, is at least aware of what he is. He has the certainty that he’s totally out of control. “I’m like a dog chasing cars,” he jabbers. “I wouldn’t know what to do if I caught one.”

But the writer of a deliciously murky horror thriller doesn’t want the audience to sympathise with the beast entirely. It’s an uncomfortable truth that veteran movie critic and thriller writer Stephen Hunter points out in his review of Michael Mann’s serial killer classic Manhunter (1986). “Frankly, [to over-sympathise with the killer] somewhat violates the ritual of the hunt. Do we want to understand these people? Isn’t the satisfaction of the moral tidiness of movies, as opposed to the messiness of real life, the pleasure we take in blowing those people away?”

Yet allowing that glimmer of understanding, that inference that there’s an irreparable psychosis at work here, that’s when a monster can really get under our skin.

We’re scared of the animal predators in Jaws and Alien, The Descent and A Quiet Place for very different reasons. Those movies effectively place us in the same situation as our Neolithic ancestors, who had little but a sharpened stick to protect them from whatever might be glaring down at them from the next rung up the food chain.

These are tales of man vs. nature, blood-and-grit survival yarns in which the monsters are driven by instinct and hunger, not to satisfy a twisted ego. We’re glad when Jaws gets blown up at the end of the movie, but we never blame him for eating all those people. Nature’s monsters are too unknowable for us to hate them, whereas the helpless human monsters of The Black Phone and The Menu play within the same moral ballpark as the rest of us. We may revel in their extermination, but there’s that spark of sympathy that might just stay our hand.

We’re afraid of helpless monsters like the Grabber because their tragedy is so unnervingly close to our own. How many times have you found yourself trapped in the ‘Skinner Box’1 of social media, thumbing through nonsense only to realise you’ve just wasted an hour? Sure, you’ll hate yourself for doing it, but you’ll do it again anyway. Lockdown exacerbated addictive behaviours related to drugs, alcohol and gambling. According to a poll published by UK charity the Forward Trust, 37% of people in recovery reported relapses into addictive behaviours during lockdown. And in what inescapably tragic roles might we be tempted to cast ourselves in an age when even social disadvantage can be commodified?

In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the villainous archaeologist Belloq gloats over the maudlin hero, “It would take only a nudge to make you like me.” It would take a lot less to make helpless monsters of us all.

Stay weird.

To read more about me, my books, comics and other projects, click right here on my LINKTREE.

Also known as an ‘Operant Conditioning Chamber’ developed in the 1930s by Harvard grad student B.F. Skinner. Designed to study the behaviour of rats and pigeons, the Skinner Box showed that if a rat were presented with a pedal that dispensed a food pellet every time that pedal was touched, then the subject would only hit the pedal when it was hungry. However, if the pedal were to dispense food at random – the way scrolling through Twitter or Instagram will randomly dispense a funny meme or juicy bit of scandal – then the rat would hit that pedal constantly.

Thank you!

Excellent article!