READ: My Future Shock Hell! (Chapter 1 of 4) How I broke into comics and why there's no such thing

READ: My Future Shock Hell! (Chapter 2 of 4) How surviving submissions means rejection-proofing your soul

READ: My Future Shock Hell! (Chapter 3 of 4) Why on Earth would you want to write comic books?

Everything I’ve gone over in these previous three chapters about surviving the submissions process - regardless of whether you’re submitting a short story or pitching a series - can be distilled into a single dictum…

GET IN BY GETTING GOOD!

This came from an interview I read with former 2000 AD editor - and outstanding comic-book writer - Andy Diggle, from Comic Heroes magazine. He said, "Everyone always asks how to break into the industry, but they never ask how to become a better writer. That's the answer - you break in by getting good at it."

I got good enough at writing Future Shocks by reading the two compilations that Rebellion had published at the time: The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks and The Best Of Tharg’s Future Shocks.

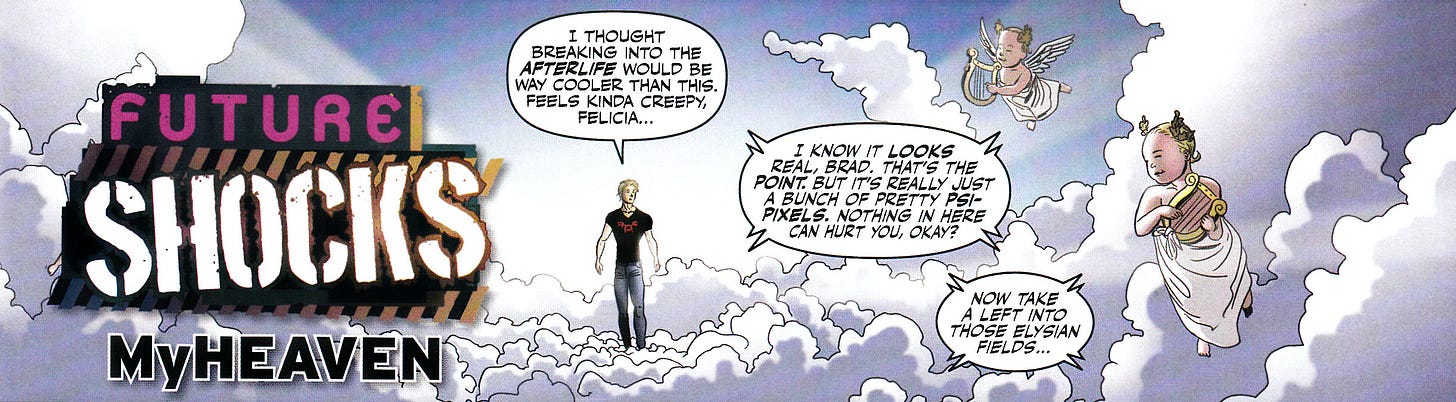

I also examined the foundations upon which the series is built. Future Shocks are short twist stories, which – never mind those found in Will Eisner’s The Spirit or classic anthology comics like Tales From The Crypt – is a form probably as old as the short story itself. While submitting my Future Shock scripts, I read plenty of twist stories by those whom I had decided were the masters of the form, particularly Saki and O Henry. I watched shows like vintage Twilight Zone and Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

I was not only reading and watching these to examine how they worked, but also to familiarise myself with the types of stories that have since become cliché. I was becoming literate in the form.

The classic advice about writing, which you’ve no doubt heard a zillion times, is to read as much as possible and write as much as possible. I’d argue these two disciplines alone are actually of limited benefit to a writer. You need to read a lot? Definitely. Write a lot? Certainly. But you also need to take time out and…

STUDY!

Let’s say you want to become a great comic writer, you’ll dutifully work your way through the classics: Eisner, Watchmen, Dark Knight Returns and everything else that’s on every ‘100 best graphic novels list’ ever written. But unless you know why you’re reading those books all you’re really doing is ticking titles off a list…

DON’T JUST READ IT, STUDY IT!

What’s so special about Watchmen anyway? I don’t know about you, but I’m so sick of hearing about that book that I could spew a kidney. Why does everyone say I have to read it? Because it’s the most Earth-shatteringly important graphic novel ever published!, they’ll chant. But you can’t just read the headline and rely on the opinions of others, no matter how unimpeachably expert they may be. Challenge everything you’ve heard about a book. Explore the context in which it was first published and approach it like you’ve never heard of it. Make up your own mind. Have the courage to disagree.

With a clear head, unclouded by the poison of hype or reverence or nostalgia, ask simple questions. What techniques is this story using? What effect does this create? What are the story’s antecedents? What’s the historical context, the circumstances in which this story was produced? What do you know about the mindset of the person who wrote it?

Take nothing for granted. Develop an aggressive, even arrogant sense of what you think works or doesn’t work. Cultivate a sense of taste. Compile your own canon. Fuck ‘the classics’.

The same goes for writing. You can write a dozen comic scripts, but if you’re not learning more about what the medium can do, experimenting with new techniques, and being brave enough to fail, then you will never improve and every script you write will suck just as much as the last one.

I believe, there’s three pillars of learning when it comes to writing anything (comics, novels, plays, anything)…

1.) UNDERSTAND LANGUAGE

2.) UNDERSTAND THE MEDIUM

3.) UNDERSTAND DRAMA.

The first is a given. If you want to write professionally, but can’t be bothered to learn how to string a sentence together, or how grammar and syntax work, then you’re the equivalent of a plumber who doesn’t know which way up to hold a monkey-wrench.

No editor worth writing for is going to accept poorly written English. If your Future Shock synopsis contains more than one typo or grammatical error, then I’m pretty sure that’s all the excuse Tharg needs to reach for another rejection slip. He’s got a filing cabinet full of these submissions, which he needs to get through before lunch.

Having worked for several years as a subeditor, I know how lazy writers can be when they think they can get away with it. Don’t be that guy!1

Challenges such as dyslexia or dysgraphia need not be a barrier to writing professionally. It didn’t stop F. Scott Fitzgerald, Agatha Christie or Quentin Tarantino. Seek information and support from organisations like The British Dyslexia Association.

As for the rest of you, there are plenty of books on grammar and style out there. I’d recommend Constance Hale’s firecracker of a style-guide Sin And Syntax for starters, as well as several of the Chambers and Oxford guides on style and plain English.

There’s no excuse, people.

The same goes for strand number two, understand how your medium works. If we’re talking comics, the bible has to be Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics (a must!) and his third book, Making Comics. I’d also recommend Eisner’s venerable but still relevant books Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative and Comics and Sequential Art. Sorted.

Now, strand three, understand drama. This is particularly relevant when it comes to writing comics because you don’t have a lot of room in which to spout reams of exposition. A Future Shock, for example, has to be this tight little six-pack of a story.

Here’s how drama works: your main character is trying to achieve something, but something or someone is standing in their way, and something awful will happen to that main character unless they achieve their goal.

That right there is the nucleus of storytelling and it goes back to the days of togas and inventing democracy. The key to understanding how it applies is to see how it exists within stories on both a macro level and a micro level, that is, to the overall story and within the smallest component of the story: the scene.

What does Indiana Jones want to achieve in Raiders Of The Lost Ark? The recovery of the Ark of the Covenant. What’s standing in his way? The Nazis. What will happen if Indy doesn’t achieve what he’s set out to do? The Nazis will take over the world.

Now let’s zoom in on that scene when Indy visits Marion at the bar in Nepal. What does Indy want to achieve at the start of this scene? He wants to convince Marion to tell him where to find the headpiece to the Staff of Ra. What’s standing in his way? Marion doesn’t want to tell him because she’s still mad at him about the way he treated her in the past. What will happen if Indy doesn’t find the headpiece? The Nazis will get it, discover the Ark’s resting place and eventually use the artefact to take over the world.

What you’re developing here is the writer’s x-ray vision, which will enable you to see through an overall premise or a single scene and identify what’s driving it. It’s the equivalent of an artist spending countless hours studying anatomy until they know instinctively how to structure a pose.

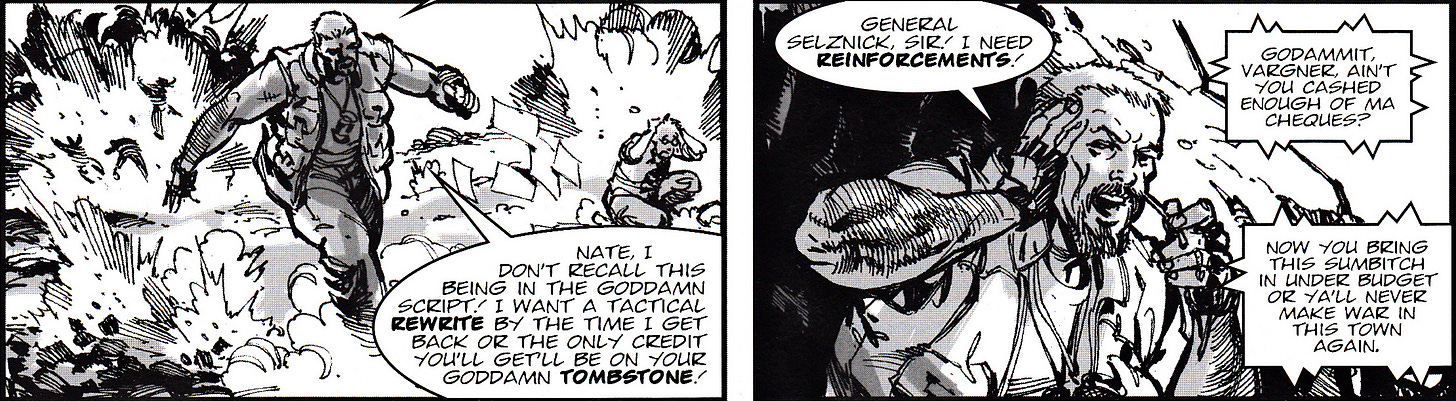

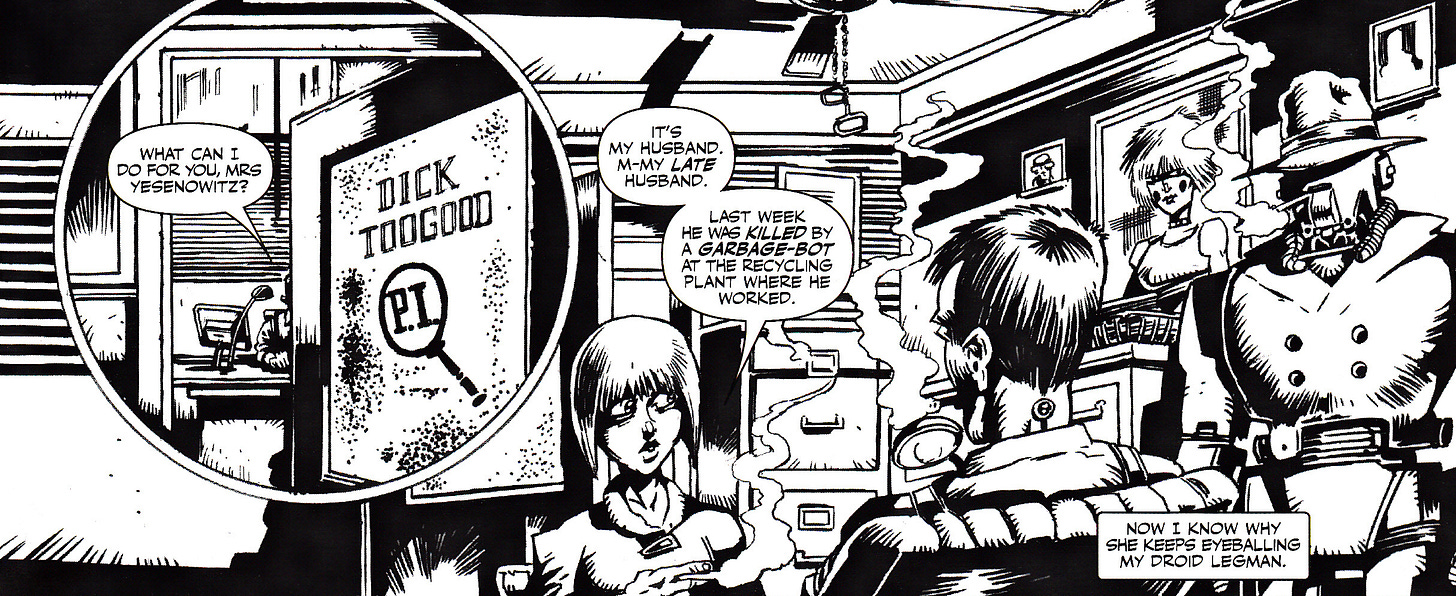

Let’s come up with a premise for a generic four-page sci-fi comic right now. Let’s say there’s a guy in space-prison. What does he want to do? Escape. What’s stopping him? Bars, security guards, perimeter guns. What will happen to this guy if he doesn’t escape? We could settle for saying he’ll spend the rest of his life behind bars, but let’s ramp it up a bit. Your stakes need to be as dramatic as possible. So let’s say he’s offended fellow inmate Big Xertlik, Anvil-Headed Nutter of Worlds, who will Scotch-kiss our hero into oblivion unless he escapes within the next hour. Ooh, a time limit. Now we’re cooking.

Now let’s zero-in on a scene. Let’s say our hero is on work detail, breaking rocks with a laser-hammer or whatever, and an alien guard is about to discover the tunnel he’s been digging and through which he was about to escape. Oh crap. The guard is striding towards him right now! What does our hero need to do? Prevent the guard from discovering the tunnel and alerting the other guards. What’s preventing the hero from doing this? This bruiser’s heavily armed and so are his buddies. What’s at stake? Horrible tortures await those who try and escape, so our hero’s going to wish he was staring up at Big Xertlik, Anvil-Headed Nutter of Worlds, if that tunnel gets discovered.

LINE OF ACTION. COUNTER-ACTION. STAKES. THE ONLY FORMULA YOU’LL EVER NEED.

Obviously, you’d need to put a fresh spin on that space-prison premise and ask a whole bunch of other questions, like what’s going to make my space-prison story different from everyone else’s? How can I make the reader care what happens to this guy? What’s the twist at the end? Notice how working up a story is about asking the right questions.

Learning about drama will help you understand which questions to ask and how you can give the best answers for the story that you have in mind.

Writers, being writers, like to romanticise, especially when it comes to writing. But don’t be fooled. The hard work involved in writing a story isn’t magic; it’s mechanics. It’s craft. It’s learnable. Yes, there’s instinct involved, but instinct is built upon knowledge and experience. As the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix once said, “First learn to be a craftsman; it won’t keep you from being a genius.”2

And it’s the same with ideas. You shouldn’t worry about being unable to generate enough ideas to keep writing scripts. Learning about drama can help you build a Future Shock idea out of anything. Check out New Scientist, Wired or Fortean Times. Find an article that tickles your interest and ask how can I turn this into a story? Who might be the main character? What might they want? Have fun…

MAKE A GAME OF IT!

Remember that freedom you felt as a kid when you were writing or drawing? Back before it all came to mean something? That lack of self-consciousness is what you’re trying to get back to.

Because that’s how you’ll stand the best chance of doing your best work.

“Among swordmasters, on the basis of their own and their pupils’ experience, it is taken as proved that the beginner, however strong and pugnacious he is, and however courageous and fearless he may be at the outset, loses not only his lack of self-consciousness, but his self-confidence, as soon as he starts taking lessons. He gets to know all the technical possibilities by which his life may be endangered in combat, and although he soon becomes capable of straining his attention to the utmost, of keeping a sharp watch on his opponent, of parrying his thrusts correctly and making effective lunges, he is really worse off than before, when, half in jest and half in earnest, he struck about him at random under the inspiration of the moment and as the joy of battle suggested. He is now forced to admit that he is at the mercy of everyone who is stronger, more nimble and more practised than he. He sees no other way open to him except ceaseless practice, and his instructor too has no other advice to give him for the present.”

Zen in the Art of Archery, Eugen Herrigel, 1948

Stay weird.

It was always the blokes. Never the women.

I found that quote in John Yorke’s Into The Woods, a comprehensive breakdown of the mysteries and function of drama, and another must-read.

Hey, Alec! Thanks for your more than valuable tips and insights. But I was wondering, I wanted to ask you, I remember reading once, I assume it was af 2014 text on these same matters, but you outlined in there a two Future Shocks tales that illustrate your points from a metaphysical point of view, that I couldn't find in these 4-parts walls of text. Or either my eyes are giving up on me.

I would give similar advice to anyone else wanting to start writing, but I'd never tell them to "fuck the classics". The classics are the best ones to learn from!