Plotting, Planning, World-Building and Head-Hopping: Reader Q&A

The Agent of Weird welcomes reader questions! If you want to ask what works for me when writing stuff about vampires, aliens and wizards, then feel free to drop a query in the comments below.

“I'd be interested in reading your thoughts on emotional arcs versus plot-driven stories. Horror seems like a good place to go heavier on the plot and lighter on the emotionality, e.g. John Carpenter's The Thing.”

It took me a while to really understand that plot and character are essentially the same thing. I’m pretty sure it was when I was watching the first season of Game of Thrones that the penny finally dropped. I saw how an action taken by a certain character – like Jamie shoving Bran out of a window at the end of episode one – triggers the next beat of the story. In this case, the next beat is that Bran didn’t die as Jamie planned. This causes the next beat of the story in which everyone else must now decide how to react. Their actions will cause another character to react, setting up the next beat, and the next, and so on, cause and effect. And if the characters are drawn well enough, they’ll often come up with those beats for you.

When you talk about character arcs, you’re talking about how the main character evolves (or perhaps devolves) over the course of a story. When you talk about plot, you’re talking about how each scene builds on the one that came before it, building towards a climax. That central progression is the same thing in both cases; one can’t exist without the other. Character studies can’t be sustained without some sort of plotted progression and a plot - no matter how spectacular - can’t survive without fleshed-out characters. For me, grasping that concept unlocked a far greater understanding of how storytelling works.

Let’s say you’ve got this idea about a guy trying to stop a company from developing an AI that he’s sure will destroy the world. You’re thinking spy scenes, car chases. Maybe the AI knows the guy is coming for him and starts controlling his own technology against him. Maybe his smartphone grows pincers and attacks him! Maybe anything with a microchip turns against him and he has to retreat to the wilds and turn Rambo. You’ve got some semblance of plot there, but your main character’s kinda foggy. Who is this guy? What background is he from? How did he find out about this AI? Was he an engineer? A janitor? A hacktivist? What meaning would this journey have for this kind of person? In this way, your plot has given you your character.

But maybe you’re not so interested in car chases and punch-ups and instead have a great idea about a bunch of characters working on this potentially world-changing tech. Maybe each character embodies a different viewpoint surrounding the whole AI debate. Developing each of those characters in a way that’ll create sparks when they bounce off each other, giving you the potential for the kind of dramatic interplay that will generate your story. One character backstabs another, which prompts the victim to fight back, which causes another to perhaps play the two off against each other, or else side with the machine. Whatever you decide those reactions to be, that’s your plot!

It's true some stories are driven more by plot and others more by their characters. Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels is all plot and no character; Before Sunrise is all character and not much plot – both work great! Take John Carpenter’s The Thing. We spend just enough time with MacReady to want him to survive (watching him get annoyed with his computer, taking charge when things get gooey, leaving his voice recordings and feeling very sorry about the situation, “nobody trusts anybody now”). Too many such scenes, too much introspection and the movie would lose momentum, and tension would sag. On the other hand, if we’d cut all those scenes with MacReady in favour of more monster-mashing, we wouldn’t have any characters to make us care about any of it.

It’s all about sensing the balance that’s right for your story.

“I would like to ask about the process of forced ideas generation, as opposed to waiting for inspiration to strike. I have a few methods but would like to know more about what others do.”

Agent of Weird: “forced ideas’? You mean writing to a prescribed topic? Like, “we need a werewolf story. Go!”…?

“Yeah, exactly. And you have no idea what to do!”

Benjamin Dickson (comics writer, artist and lecturer)

It depends. If an editor asks me to pitch a story set in a pre-established universe or around a specific theme or subject, I might have an idea knocking around that I’ve been wanting to write for ages. Or else, I’ll start doing some research into the topic or the world they’ve given me, during the course of which something will spark my interest. Either way, I find it’s about asking those questions most likely to yield an idea that I’m interested in exploring.

“Ask what [a genre is] afraid of, what it’s trying to hide – then write that.”

M. John Harrison

A great example of Harrison’s thinking here would be the 1974 Mel Brooks movie Blazing Saddles. The first draft of the screenplay was written by Richard Pryor, who recognised the unspoken racism of the Western genre and made that the story. Like Pryor, think about how the kind of story you’ve been asked to write usually plays out and explore a different direction, a different angle. What assumptions does this genre or type of story usually make? What kind of character do you rarely see? How have you always felt about this kind of story? Uncomfortable? Intrigued? Nostalgic? What would you bring to a story like this based on your unique background and life experience?

This is the reason why diversity – not just diversity of race and gender – but diversity of experience, of class, personality and thought are so intrinsic to storytelling. Because it’s those new ideas that are gonna make the story feel fresh and unique. We’re familiar with the story of Superman, but when you tell that story with Luke Cage, the notion of a man able to bounce bullets off his chest suddenly takes on a whole new cultural meaning, which takes the story off in a fresh direction.

That said, don’t be one of those writers who takes their readership for granted.

If you’ve been asked to contribute a story idea for a pre-existing universe, it’s more than likely the editors will have a very specific readership in mind. Don’t be shy about asking them if you’re not sure. If you’re reaching for that personal angle, you’ll need to marry it to the readers’ interests. Don’t become so self-interested that you forget about the people paying a tenner to be entertained. Can you make them interested in what you have to say? Are you clever and subtle enough to make them care? No one likes eat-your-greens storytelling.

“If you want to tell people the truth, you’d better make them laugh or they’ll kill you.”

George Bernard Shaw

Again, if you’re writing within a specific universe, whether it’s Star Wars or whatever, bear in mind that most of those readers are more interested in Star Wars than they are in you, the writer. Bring something new to the table, by all means, but don’t make it all about you. Again, it’s all about balance.

So, whether I’m working on an idea I already have, or have been handed a world or topic to play with, I’ll start by asking basic logical questions. Who would be the most interesting character to put in this situation? How would a setting like this work? I’ll spend a little time doing focused research and looking for answers that could potentially take me to the end of a story.

“How much do you plan in advance? Do you plot everything out, or do you feel that makes the work too stilted? Do characters/plots ever surprise you?

Also, what do you do when you feel like it’s starting to go wrong….

I think method stuff is pretty interesting. Just when and where you write, how long. Do you try and lay everything out and then edit it, or revise it as you go. That sort of thing.”

Denny Flowers (author)

I plan as much as I can in advance and like working from a very detailed synopsis. I know writers who don’t plan at all because it feels like they’re ironing all the spontaneity out of their stories before they’ve even started. I see their point, but – for me – I still don’t know what’s going to happen until I’ve started writing the scene, no matter how thoroughly (I think) I’ve planned it. I don’t know what those characters are going to do until I’ve put them in that scene.

There were several instance during the writing of my Warhammer Crime novel The Wraithbone Phoenix when the characters just started doing their own thing. I was in the middle of a tense stand-off scene when the ogryn Clodde started relieving himself in a filing cabinet, which he later used to beat someone to death. That was all him! Similarly, I knew that the malevolent yard-keeper Scratchwick would be taken hostage by the Eastwoodian bounty hunter, Ocastus Forl. What I didn’t know was just how much Forl would develop paternal feelings for the youth and end up caring so much about setting him straight. Again, that was the characters, not me.

WHY WON’T CHARACTERS DO AS THEY’RE TOLD?

Do characters really have a life of their own? Or is it all just marketing bunk and cultural mythmaking? Do writers really commune with the unseen?

A full synopsis gives me at least a shot at a proof-of-concept framework from which to work, so it’s one less thing to worry about once I start writing. George R.R. Martin is often cited as someone who doesn’t know where a story will take him and will happily let his muse lead him over hill and dale. However, George R.R. Martin has rather a lot of money in the bank and doesn’t have to worry so much about invoices and deadlines. So, I’m a plotter, for sure. I want both me and the commissioning editor to know where I’m heading, while leaving plenty of room for the characters to live and breathe.

If I can feel it starting to go wrong, I’ll usually just leave a note for myself and crack on, happy to deal with it during the edit. But if it’s something that threatens to derail the plot and stop me moving forward, then everything comes to a halt until I can get it fixed. I’ve found, however, that a major cause of writing breakdowns is not thinking through a particular concept or background. Another reason why I’ll plot in advance.

If I’m writing in the weird and wonderful genres of sci-fi, fantasy and horror, I want to at least have an idea of the tone I’m after, the boundaries of magic, the supernatural or the super-scientific. But it’s the same if I’m writing something more down-to-earth. When I wrote the graphic novel The Coffin Road for John Carpenter’s Night Terrors, the main character drove a breakdown truck, but I didn’t do enough research into how breakdown drivers operate. At one point in the story, I couldn’t quite rationalise why he would bother towing a wrecked vehicle (which I needed him to do) when it might have been safer to come back for it in the morning. The story suffered its own minor breakdown, while I had to go speak to a friend of a friend who worked for the AA!

If I’m setting sail on a writing mission, I want to make sure the boards of my story-ship are as watertight as I can make them, and to have a half-decent map and compass to hand.

“How do you decide the “right” level of description when world-building?”

Dan Marshall

Less is more, generally. I think it works to have a very clear idea of the world that you’re building (or exploring if it’s a world that’s pre-existing). I’ve learned not to over-describe when writing prose. You really need to meet the reader halfway and let them imagine this world for themselves. If you’re too prescriptive and insist on describing every last nuance of your magic system or how you’ve decided trade embargoes work in post-apocalyptic world, then it starts reading more like a rulebook. More like a Dungeon Master’s Guide or a world bible than a living, breathing story.

World-building in comics and movies don’t work in the same way as fiction, of course. These are visual media, so the world is built for you to a much greater degree, and you don’t have to do as much imagining. But bear in mind how movies like Blade Runner and comics like Hellboy feel lived in. They concentrate on the effect that world has on the characters, rather than stopping to exhaustively catalogue the world itself. This is basic ‘show don’t tell’, I guess. Which is just another way of saying ‘dramatize don’t explain’.

A lot of the bad habit I had of over-describing make-believe worlds in fiction came from years of writing comic scripts, I think, where all that cold, exhaustive description is necessary to direct the poor artist, who has to do the majority of the hard work of putting that world on the page.

“What are your thoughts on head hopping? Is it something you would always aim to avoid, or are there times when skipping between POV characters (within a chapter) can be effective?”

Michael Dodd, Track of Words (SFF Book Reviews, Interviews and Articles)

I almost always stick to a single PoV within a single scene, but that’s just me. The stuff I write is pretty user-friendly (for now). If I’m shifting perspective to look through the eyes of another character, then I’ll add a paragraph break to let the reader know we’ve changed view. (Although that doesn’t always translate when the book goes to audio…) Otherwise, it’s easy to end up disorientating people, which is how I felt reading Dune for the first time. Whether that was a deliberate attempt to evoke a particular sense of communal thought or else a flaw in Herbert’s technique is up for debate.

When I wrote my Judge Anderson novellas, I was literally hopping into different people’s heads, but that effect was couched in Anderson’s ability to read people’s minds. So the reader (hopefully) knew where they were at all times. As with any technique, it depends, I think, on the effect you’re going for,

I’m pretty sure I read someone arguing somewhere that Hemingway head-hops in The Old Man and The Sea. I’ve still got a post-it note in my copy of the book...

“It made the boy sad to see the old man come in each day with his skiff empty and he always went down to help him carry either the coiled lines or the gaff and harpoon and the sail that was furled around the mast…

The old man had taught the boy to fish and the boy loved him…

They sat on the Terrace and many of the fishermen made fun of the old man and he was not angry. Others, of the older fishermen, looked at him and were sad. But they did not show it and they spoke politely about the current and the depths they had drifted their lines at and the steady good weather and of what they had seen.”

But really this is the omniscient narrator merely observing in general rather than sitting in the cockpit of a given character.

So, yeah, head-hopping is a fairly hard ‘no’ for me, unless the writer has some specific effect in mind and knows how to keep me on point.

Acrobatic Flea: How does one go about adapting someone else’s “vintage” creation to a modern audience, without losing the “magic” that made the original stand out?

Tim Knight (HeroPress)

For me, it starts with going back to the original and figuring out what makes it work, both for me and for long-term fans. I do this pretty much every single time I’m working within a pre-existing story-world.

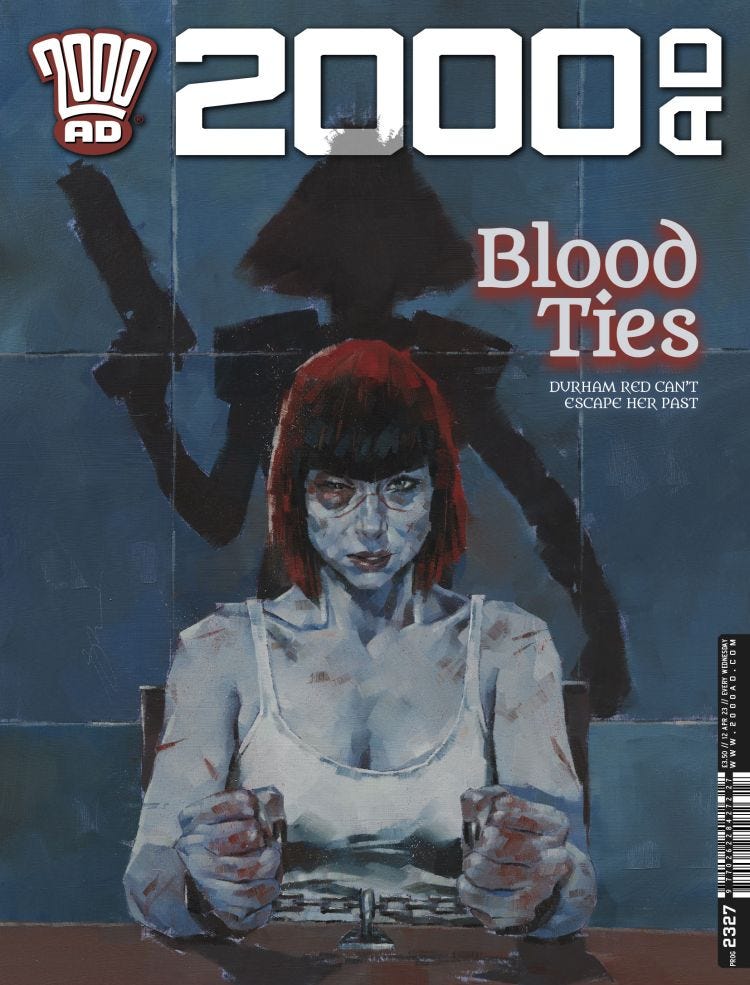

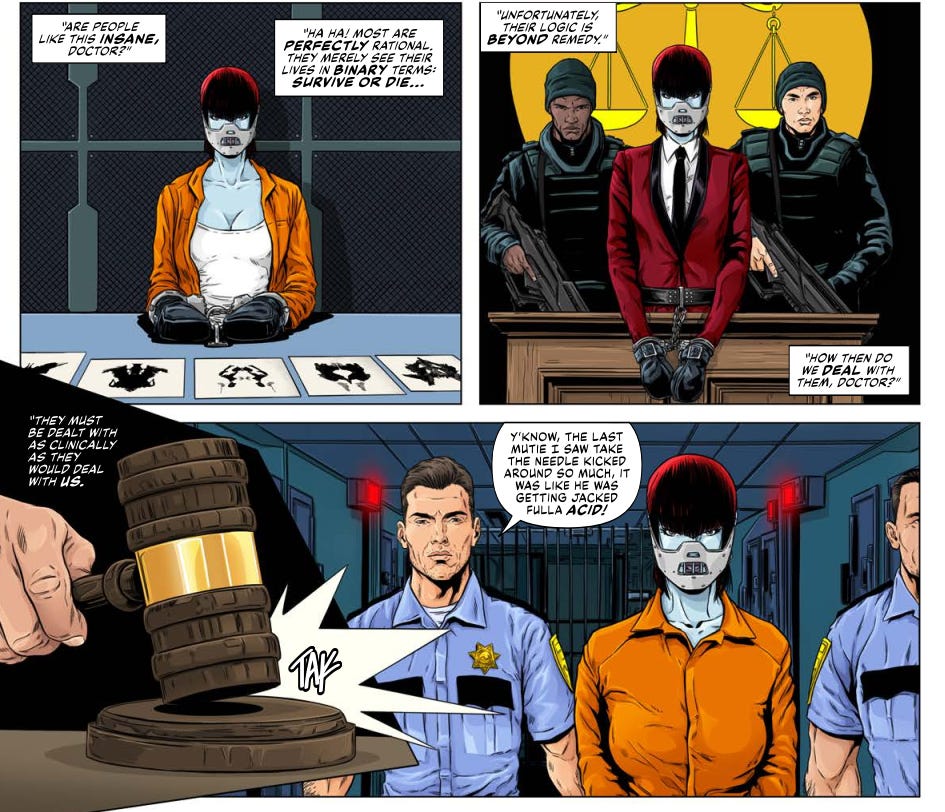

In the case of Black Beth, there was no fanbase whatsoever. I didn’t know anyone who had read and loved Black Beth when she first appeared in that Scream! Special back in the day. So I was trying to figure out what made that character appeal to me personally, and how I could broaden it out and build a bigger fanbase. If it’s a pre-existing character with a much wider following, like Judge Anderson or Durham Red, I’ll try and pinpoint the overall appeal. Why do people like these characters? What makes them work? What’s your interpretation of all this?

There’s usually a very good reason why certain characters endure. It’s usually something quite deep-seated and archetypal1. If you can find a good dramatic tension at the heart of a character, then you’ve really struck gold. I found that with both Judge Anderson and Durham Red.

With Anderson, she’s the most empathetic person in all of Mega-City One, yet she’s also part of the terrible fascist machinery that’s crushing everyone’s souls. She wants to help, but she’s part of the problem. Similarly, Durham Red is a murderous vampire. That’s exactly why everyone in the galaxy is so terrified of her in that first series by Grant and Ezquerra. But how does she cope with that as a person? I don’t think she’s a psychopath, which must only make it worse for her. She kills to survive. Her addiction to blood won’t let her go cold turkey. And on the deepest, most primal level, she would relish killing and consuming the lives of others. She’s Lestat and Louis all in one. But once she’s sated her vampiric appetite, how does she deal with the comedown? How would she maintain a moral compass? Stuff like that is your story-engine. What stories can you tell that would bring out that conflict and raise those dramatic questions?

So in terms of going back and revising vintage creations, it’s a case of reviewing (and revering) the original2, and figuring out what makes them tick. I’ll usually read plenty of interviews with the original creators, as well as fan responses. Fans sometimes get taken for granted on that score, I think, when they’re the people who’ve probably lived with those characters the longest.

Thanks to Sweet Nightmares, Benjamin, Denny, Dan, Michael and Tim for their questions

Stay weird.

For example, I’ve often felt there’s something weirdly paternal about Judge Dredd. For me, he embodies exactly how little boys in the seventies might have felt about their dads – this authoritarian monster who, nonetheless, would have died to protect those under his care.

Why anyone would write a character they hate is beyond me.

Thanks Alec. Regarding your comments on Red, I agree that is the interesting aspect of the character. Those elements you highlighted, but also how she deals with being rejected by everyone. She's rejected by society because she's a mutant, but she's rejected by fellow mutants (including her lovers, like Alpha) because she's a vampire. She's the ultimate outsider.

I totally agree on the character vs plot arc argument. Some of my favorite scenes and lines that I’ve ever written were totally organic, just putting the characters in a spot and seeing what they do and say.