Telling a Superhero Story the DC Way

Choosing myth over Marvel in James Gunn's Superman (2025)

This year’s Superman opens with the Man of Steel lying spent and bloody on the Arctic tundra. It’s a perfect metaphor for the state of the world’s founding superhero after the battering he took under DC’s chaotic Extended Universe project. An uppercut from the ponderous Man of Steel (Zack Snyder, 2013), a one-two from the joyless Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (Snyder, 2016), a body-slam from whatever the hell Justice League was supposed to be (Snyder and Joss Whedon, 2017), then a four-hour beating with a folding chair by Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021).

Thankfully, Kal-El is rescued by a couple of playful white-haired goofballs: Superman’s dog Krypto and writer/director James Gunn, Disney divorcee turned DC Studios CEO.

Supes gets his solar batteries recharged to the tune of John Williams’ still-goosebump-inducing score before the story brings us up to speed faster than a speeding bullet.

It turns out Superman has just had his butt handed to him by a foreign metahuman, payback for Superman taking it upon himself to prevent a landgrab by the hostile Slavic nation of Boravia.

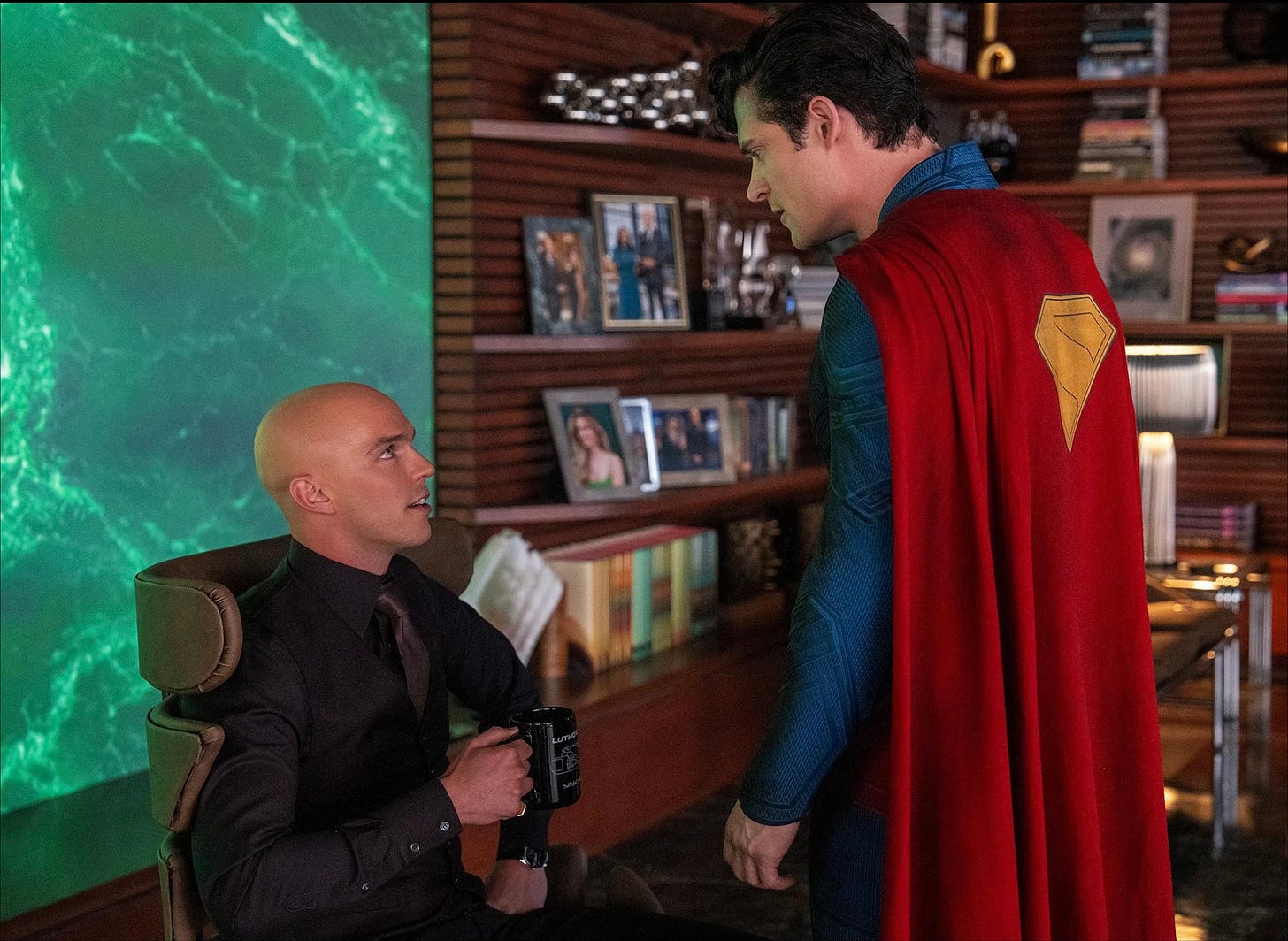

The adults in the room are Lois Lane (an astute Rachel Brosnahan) and Lex Luther (a twitchy, combustible Nicholas Hoult). One tries to convince Clark Kent that maybe inserting himself into the affairs of an aggressive but allied nation maybe wasn’t such a good idea; the other takes the opportunity to turn the tide of public opinion against Superman and get him cancelled from reality.

Gunn’s cinematic rescue mission is a spectacular success, one that restores Superman’s status as a cultural – not just a fanboy – icon. Those expecting another corporate superhero clusterf*** will be surprised by an IMAX-worthy event movie made with heart and no small amount of craft.

And it’s only a smudge over two hours long. Great Ceasar’s Ghost!

Perhaps the movie’s greatest feat is finally moving the character out from under the shadow of the first two Christopher Reeve movies, Superman (Richard Donner, 1978) and Superman II (Richard Lester, 1980). (I still have some love for Superman III [Lester, 1983], though that’s probably just 11-year-old me talking.1)

Reeve’s Superman was a graceful Olympian, the perfect dad, with laser-blue eyes, a neck like the Washington Monument and a chest the size of Pennsylvania. Much of the beauty of Reeve’s performance in those movies was his ability to morph from stuttering Clark Kent to Man of Steel with a single intake of breath.

Another relative unknown, David Corenswet is almost a decade older than Reeve was when he first took the role (Reeve was 24, Corenswet is 32), though Corenswet’s Superman feels a great deal younger.2

His Superman is the Big Blue Boy Scout, chunky, dimpled, and eager to take on the world. He doesn’t so much fly as tumble through the clouds like a labrador chasing a tennis ball. We learn he’s only revealed himself to the world three years ago and it feels like we’re seeing the messy-years version of Superman we never saw in the Donner original. That movie made a ten-year cut from angry teen Clark booting footballs into orbit to the adult Kryptonian taking his maiden flight from the Fortress of Solitude.

Gunn understands that Superman was always a dork. Batman is forever the epitome of badass cool, while Wonder Woman is too regal to ever get riled by internet trolls. The way Superman frets over the most humane way to despatch a monster has his fellow metahumans rolling their eyes. He always says ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ and has the same taste in music as your dweeby kid brother.

Lois and Clark’s relationship brings the heat, while Ma and Pa Kent’s blue-collar coziness brings even more heart. There’s a moment between Clark and his taciturn adoptive dad (Pruitt Taylor-Vince) that will put a golf-ball in the throat of any man. It’s moments like this that anchor the comic-book world you’re being asked to buy into; without the humanity, the superheroic sturm und drang is as meaningless as it was in the Snyder movies3.

If there’s a weak link in the cast it might actually be Lex Luther. Nicholas Hoult brings a tense, jittery energy to just about everything he does (Fury Road, Nosferatu, The Menu) and the concept behind his Lex is great. Clickbait is the movie’s Dune-spice; he who controls the algo, controls the universe. This Lex is a Muskian tech-guru surrounded by a cult of fawning, young lackies. He puppeteers his automaton soldiers by yelling key-stroke combos for every punch. He’s literally a keyboard warrior.

But Lex’s fragility is perhaps a little too evident. He’s more pathetic than scary, and less memorable than scene-stealing oddballs like Edi Gathegi’s stoic cyber-wiz Mr Terrific, Nathan Fillian’s gum-chewing, bird-flipping cowboy Guy Gardner and Sara Sampaio’s maybe-not-so-ditzy Miss Teschmacher (an interesting carryover from the first Donner movie).

The superhuman slugfests don’t lose you in VFX soup, while Henry Braham’s sunny cinematography and John Murphy and David Fleming’s radiant score combine to hit you like a beam of restorative solar goodness. We get one self-conscious ‘Gunnism’ – a goofy-cool bit of action set to jukebox bubble-gum – which might be annoying if the scene weren’t so damn funny.

While Snyder’s movies offered a chillier, edgelord version of ‘real-world’ superheroes, Gunn doesn’t follow Marvel’s lead. Instead, he embraces what made DC Comics so distinct from their rival and goes back almost a century to rediscover the primal appeal of the world’s premier superhero.

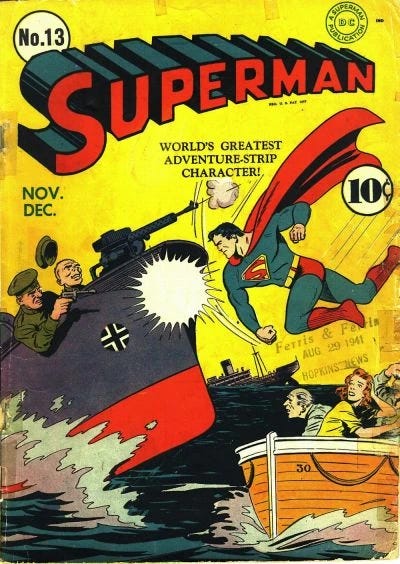

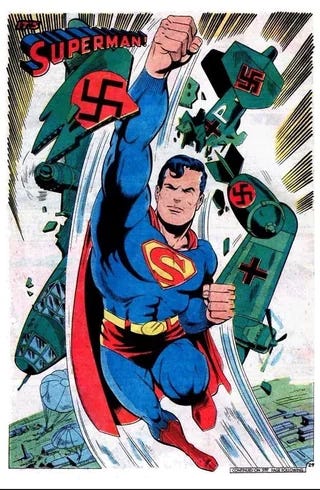

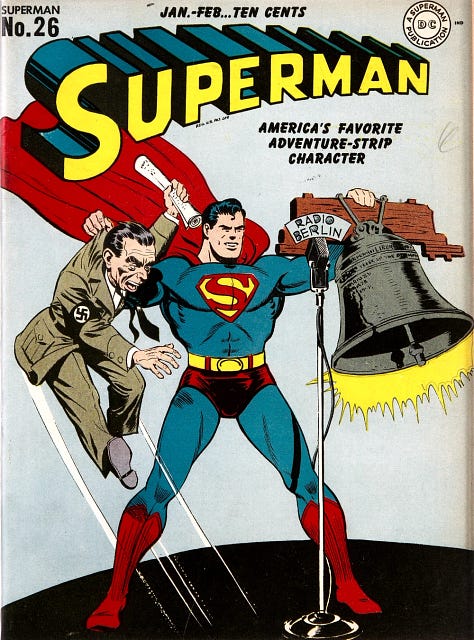

Superman first appeared in Action Comics #1 in April 1938 (he’ll enter the public domain within the next ten years). He was the creation of writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, a couple of blue-collar sci-fi nebbishes from Depression-era Cleveland, sons of Jewish immigrants forced to flee the advancing Reich.

The alien foundling who became an American folk hero, Superman is unquestionably the story of Jewish-American assimilation: the dual-identity, the golem born of pulp-clay to defend the defenceless, the dark-haired, anti-Aryan übermensch who inaugurated the proud American tradition of superheroes knocking dictators on their asses.

In mythological terms, Superman is up there with Moses and the sun gods, hewn from the same primordial bedrock as Ra, Surya and Helios. He’s as Jungian as they come.

He speaks deeply to lonely little boys who yearn to fit in, to self-improve and impress, to conquer their troubles and liberate their bodies.

“As he watched Joe stand, blazing, on the fire escape, Sammy felt an ache in his chest that turned out to be, as so often occurs when memory and desire conjoin with a transient effect of weather, the pang of creation. The desire he felt, watching Joe, was unquestionably physical, but in the sense that Sammy wanted to inhabit the body of his cousin, not possess it. It was, in part, a longing--common enough among the inventors of heroes--to be someone else; to be more than the result of two hundred regimens and scenarios and self-improvement campaigns that always ran afoul of his perennial inability to locate an actual self to be improved. Joe Kavalier had an air of competence, of faith in his own abilities, that Sammy, by means of constant effort over the whole of his life, had finally learned only to fake.”

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (

, 2000)It was Superman, Batman and Arnold who got us straining at our dumbbells so the arseholes at school might think twice before trying it on and the girls might give us a second glance.

But Superman was the one who gave us a moral compass, got us wanting be the good guy.

Even the story of Superman’s creators is the stuff of foundational legend, albeit legendary horror, a cautionary tale told to frighten young comic creators into guarding their ideas.

Siegel and Shuster sold the rights to Superman for the grand sum of $130 between them. Their creation went on to earn his publisher millions, established an American art form, and helped build the industry that would eat his creators alive.

It wasn’t until artists Jerry Robinson and Neal Adams took a stand during the run-up to the first Superman movie in 1978 (at the risk of their own freelance careers), protesting Time Warner’s neglect of Siegel and Shuster, that the company finally relented. They granted Superman’s creators (then broke and in their mid-60s) an annual pension, healthcare and their names attached to the iconic character in perpetuity.

There’s a reason legendary news anchor Walter Cronkite gets a namecheck in Gunn’s movie; it was Cronkite who broke the story of the Timer Warner agreement.

DC Comics has always trafficked in gods.

Superman became the bedrock upon which the publisher founded their superhero empire, forming a holy trinity alongside Batman and Wonder Woman. The only flaw in this pantheon was its flawlessness.

When Marvel Comics’ Fantastic Four #1 arrived in 1961, they offered a decidedly post-war take on superheroes, a flawed, dysfunctional family that bickered and pranked each other, fighting supervillains not in lofty fairytale Metropolis but among the garbage-cans and graffiti of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, right on many readers’ doorstep.

Next to scrawny neurotics like Spider-Man and the messy, diverse, found families of the Avengers and X-Men, DC’s aliens, billionaires and Amazonian royalty couldn’t help but feel aloof and unrelatable.

The Marvel cinematic universe got through its best years on the wisecracking believability of its comic-book sources. Movies like Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) and The Avengers: Infinity War (2018) work hard to rationalise their source-comics, come up with plausible reasons for the silly names, take a stab at explaining superpowers through the lens of real-world physics. The costumes look functional, the geopolitics (kinda) credible, the streets familiar, the cinematography realistically drab.

The best Marvel movies never stray too far from our own world, even when that world is being demolished by aliens or its citizens snapped out of existence.

James Gunn’s Superman instead does what DC Comics have always done best, leaning into something more absolute, closer to myth or fairy tale. Marvel Comics always presented its stories as, “the world outside your window”, but the world outside your window in Gunn’s Superman is more likely to contain a giant space-anemone fighting a Green Lantern like it’s really not much to worry about.

It’s a world so saturated in gods and monsters that even its strangest characters don’t need much of an intro. The movie doesn’t need to show how an axolotl-monster grows from fire-belching toddler to roof-crushing kaiju, because it knows how familiar we are with this sort of thing. When office blocks wade into each other like great, crumbling dominoes, we don’t need to ask how anyone could possibly have survived.

Thanks to seventeen years of Marvel superhero movies, there’s less justification required for the delirium to make sense.

By embracing the ridiculous rather than apologise for it, Gunn’s Superman captures the wonder of being absorbed in a vintage superhero book.

It treats us like children – in a good way.

“It’s adults who have the most trouble separating fact from fiction. A child knows that real crabs on the beach do not sing or talk like the cartoon crabs in ‘The Little Mermaid’. A child can accept all kinds of weird-looking creatures and bizarre occurrences in a story because the child understands that stories have different rules that allow for pretty much anything to happen.

“Adults, on the other hand, struggle desperately with fiction, demanding constantly that it conform to the rules of everyday life. Adults foolishly demand to know how Superman can possibly fly, or how Batman can possibly run a multibillion-dollar business empire during the day and fight crime at night, when the answer is obvious even to the smallest child: because it's not real.”

Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human (GrantMorrison, 2000)

The superhero narrative was originally conceived for the consumption of children and as such can withstand only a limited amount of adult scrutiny before the concept breaks. Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen is the classic chronicle of just such a breakdown.

The geopolitics in Superman are as terrifyingly naïve as Superman himself. The movie even glosses over one late-in-the-game detail that would have triggered World War Three here in the real world.

But we’re not in the real world and it’s okay to be a kid again for just a couple of hours.

We’re adults, after all, and know when to put aside childish things. We recognise a metaphor when we see one. We understand satire and would never get suckered by obvious fictions. We don’t need YouTube videos to explain how Gladiator II wasn’t a documentary. We all know where the line between fantasy and reality is drawn these days, right?

*Anakin stares.*

Right?!

Superman’s much-anticipated political coda turns out to be pretty brazen.

It speaks of a dangerous ideology conceived years ago by radical activists named Bill S. Preston Esq. and Ted Theodore Logan, who beseeched their followers, “Be excellent to each other.”

It should be impossible to hate on a movie that so wholeheartedly champions basic, human decency.

How did we reach a point where Superman felt so needed?

Recommended Reads (all standalone, easy-to-pick-up graphic novels)

The Man of Steel (John Byrne, Dick Giordano, 1986)

Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow (Alan Moore, Curt Swan, 1986)

Kingdom Come (Mark Waid, Alex Ross, 1996)

Superman for All Seasons (Jeph Loeb, Tim Sale, 1998)

Superman: Birthright (Mark Waid, Leinil Francis Yu, Gerry Alanguilan, 2003-04)

Superman: Red Son (Mark Millar, Dave Johnson, Andrew Robinson, Walden Wong, Killian Plunkett, 2003)

DC’s The New Frontier (Darwyn Cooke, 2004)

All-Star Superman (Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Jamie Grant, 2005-08).

Add your own recommendations in the comments.

And stay weird.

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

That stupid kid loved it when Superman got wasted on Jim Beam and turned the bar into a shooting range by flicking peanuts everywhere, then had a fight with himself in a junkyard. (I recall the MAD Magazine send-up had him hand-buzz the Pope as well.) Oh, and that bit when the bad lady got sucked into the computer and turned into a silver-eyed death machine. That was cooooool! I suspect this kid also had a thing for Lana Lang.

Fun fact: Corenswet is the grandson of Edward Packard, the writer/creator of the Choose Your Own Adventure gamebooks.

And before anyone goes off on one, I actually like Snyder, though find his earlier movies the most interesting. His Dawn of the Dead remake (2004, from a script by Gunn) is brilliant and 300 (2006) is a filthy pleasure of mine.

Wonderfully written review! I enjoyed reading it almost as much as watching the movie! I have little patience for the "but what if it was REAL?" take when it comes to superheroes, so this movie seemed to hit the perfect tone, for me. Grant Morrison was right about kids not caring where Batman got the tires for the Batmobile, and pulling that thread too hard on any superhero story inevitably causes the whole concept to unravel.

I liked Deborah Joy Levine's take on the character in the first season of Lois & Clark. She'd been told Superman wasn't interesting because he was too powerful, and she saw that was exactly what would be interesting -- because he wanted to connect with people and his powers got in the way. She also remembered that the character is super-intelligent as well as super-strong, something missing from all the over-angsty versions.