Science Fiction Double Feature: The Crow (comic book vs. movie)

The 1989 comic by James O'Barr and the 1994 movie starring Brandon Lee share the same melancholy heart, though it beats in very different ways

Fantasy, according to Ursula K. Le Guin, “is a different approach to reality, an alternative technique for apprehending and coping with existence.”1 The genre speaks the timeless language of symbols and metaphor, of strange transformations and grail quests and Big Bad Wolves. Such allegory lends form to the ineffable, speaks the unspeakable, wrings meaning out of meaningless chaos. No wonder the genre has proved so adept at processing trauma.

Reeling from a cancer diagnosis in the early 1980s, fantasy author David Gemmel threw himself into writing the book that would eventually be published as Legend (1984), the saga of an ageing but dutiful man facing his last stand within a body of stone besieged by a malignant invader. In Maus (1980-91) graphic novelist Art Spiegelman comprehended his parents’ survival of the holocaust through the symbolic hierarchy of animal fable, casting Jews as skittering mice and the Nazis as rapacious cats. “The mouse metaphor allowed me to universalise,” Spiegelman says. “To depict something that was too profane to depict in a more realistic way.”2

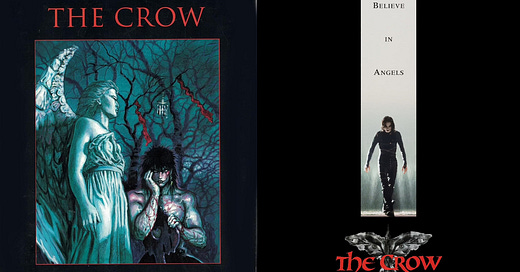

Another comic-book roman à clef, James O’Barr’s The Crow (1989) was among several key texts in the goth subculture of the early 1990s, including DC Comics’ The Sandman (1989-96) and the White Wolf role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade (1991). Readers more familiar with The Crow from its later, trashier movie adaptations might be forgiven for thinking the source-comic is merely the stuff of violent adolescent fantasy, fit only for potential school-shooters and teenage poets with too much eyeliner. But the comic needs to be read with at least some knowledge of what drove writer-artist James O’Barr to create it. Like Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, The Crow is best read as symbolic biography.

According to O’Barr himself3, his birth-mother was too blitzed to remember exactly when he was born, so the Detroit care-system had to date his birthday as 1 January 1960. He spent much of his childhood in the care system, loaned out on weekends to potential foster parents, some of whom “shouldn’t have been allowed to have pets, let alone children.” He learned to stay quiet, struggled to communicate and taught himself how to draw from studying classical paintings and Michealangelo sculptures. At age seven he and his brother were adopted by a stern, hard-working couple who forbade James from drawing in the house as it would never help him get a job.

He fell in love at age 16. She was charming and funny and brought him out of his moods, and he loved her with the kind of fervour only a young man deprived of love for so long can feel. They hoped to marry after graduation, but she was killed one night by a drunk driver.

O’Barr tried hard not to self-destruct. At 18, he joined the seminary, then the marines, then picked up a pen and began drawing The Crow, the story of a man who returns from the dead as a homicidal Pierrot with a vendetta against the scumbags who murdered him and his fiancée.

Discharged from the corps, O’Barr returned to Detroit and worked in the body shop of a car dealership, sweating 8-10 hours a day before coming home and drawing until the early hours, fuelled by rage, cigarettes and Joy Division LPs. Initially, he planned to do nothing more than abandon The Crow once it was finished, a project whose sole purpose was its very creation. “It was basically something I just did for myself,” he says. “I had no intentions of publishing it anywhere. I never showed it to anyone. It was just this vehicle for me to, y’know, this cathartic-type thing that was supposed to be helping me.”

It took him nine years to complete the book, by which time he had shopped it around a few publishers. None of them got it. They told him no one wanted to see their hero crying or else wanted to turn it into a Punisher knock-off.4

By 1988, Gary Reed, founder of Caliber Comics - and then-manager of O’Barr’s local comic-book store - was looking to set up a publishing company that could showcase all the burgeoning talent that frequented his shop (Guy Davis and Vince Locke among them). The Crow eventually launched under Caliber as a five-part limited series in 1989 and quickly burned through its initial 10,000-copy print-run. Issue one eventually sold around 30,000 copies according to Comic Scene5, spectacular figures for a low-rent indie book. Trade collections found their way into record stores, attracting readers from the music scene, and gaining The Crow a fierce cult following.6 O’Barr has joked that the ‘Goth Starter Pack’ back then came with a Cure album, a pair of Doc Martins and a copy of The Crow.

Published when North American comic books were on a cultural upswing in the wake of The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen (both 1986), The Crow has little in common with its more respectable peers. It’s not a construct of visionary intelligence like the writings of Alan Moore. It has none of the puckish literary allusions of The Sandman. It’s a resounding primal scream and no less powerful for its incoherence.

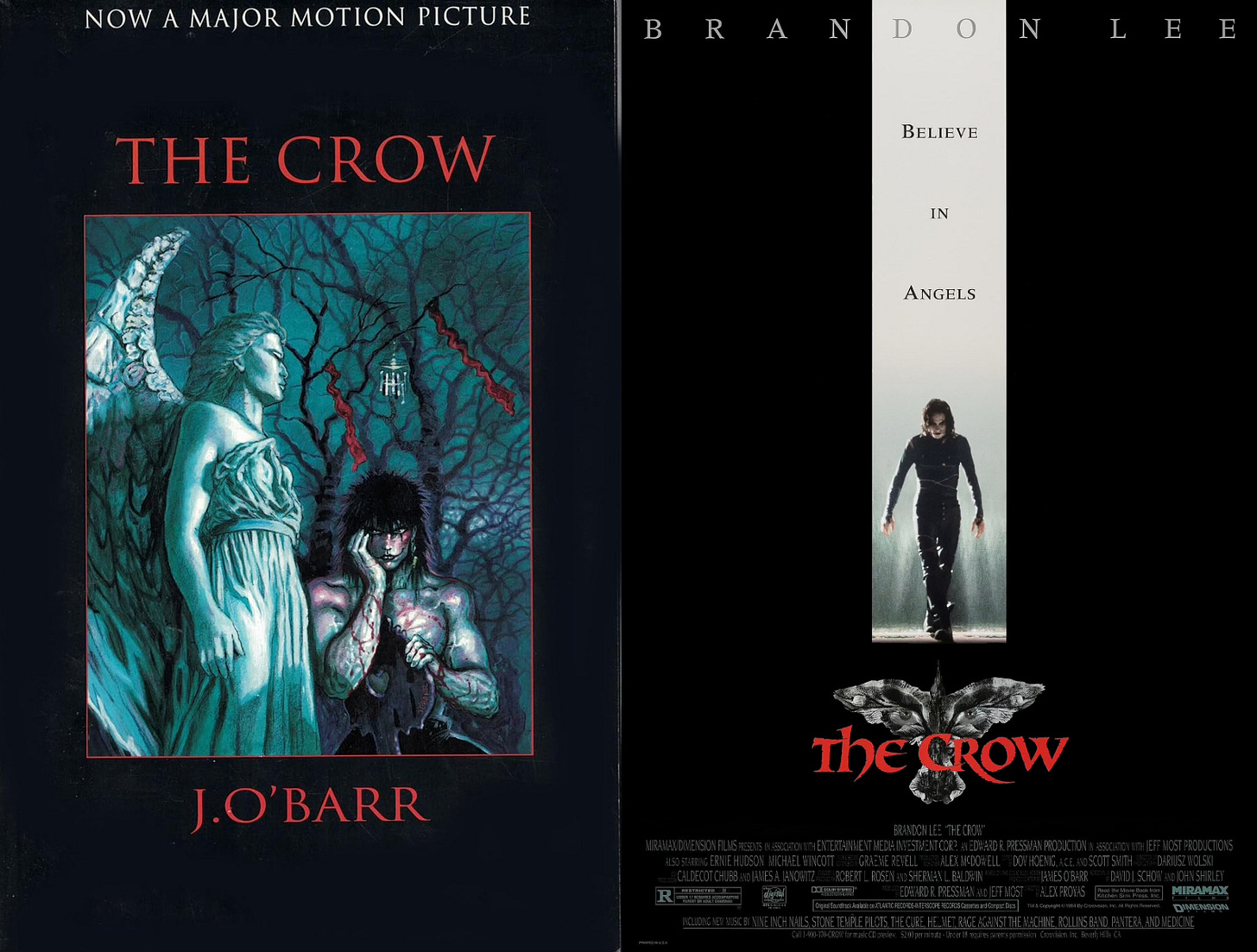

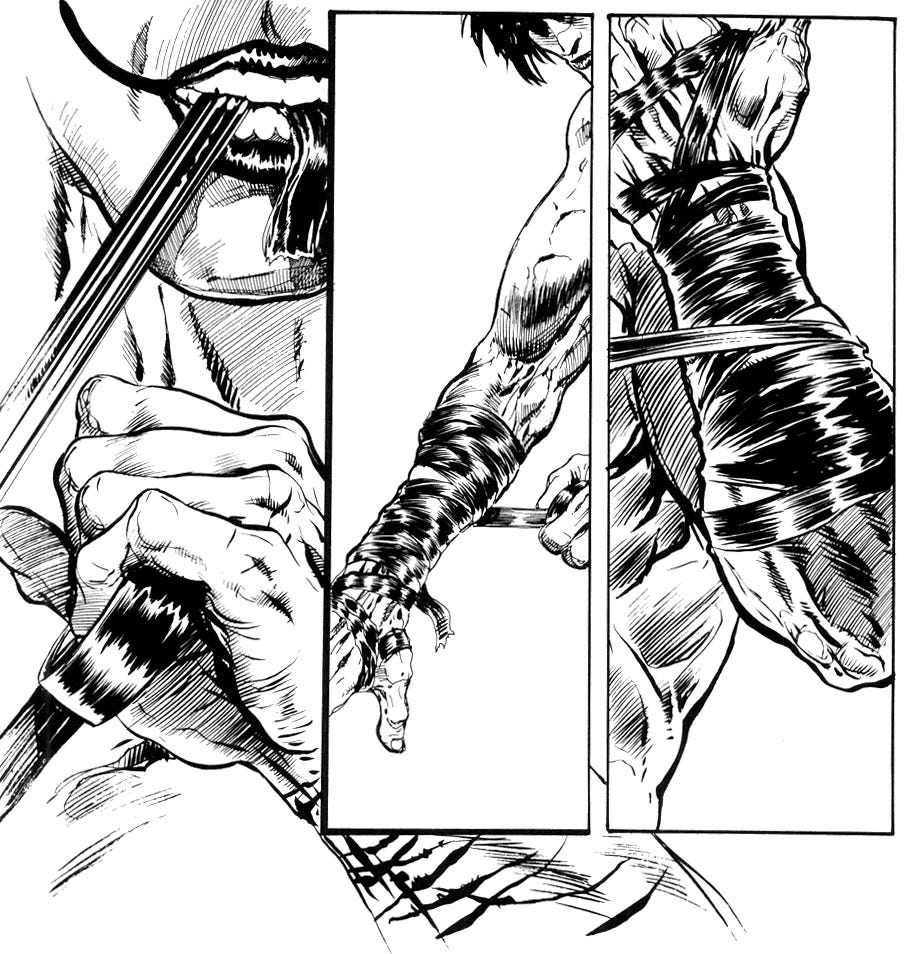

O’Barr’s monochrome artwork is obsessively detailed, his noirish cityscapes clearly influenced by The Spirit (Eisner gets a storefront name-check) but rendered in scratchy, grungy lines, abyssal blacks and heavenly white spaces. Billed as a love story, The Crow is really more like a dirge: melodic, funereal, broken, an outpouring of grief that’s by turns irrational, lucid, brutish, beautiful, poetic, inarticulate, a chaos of feelings struggling to find order on the page.

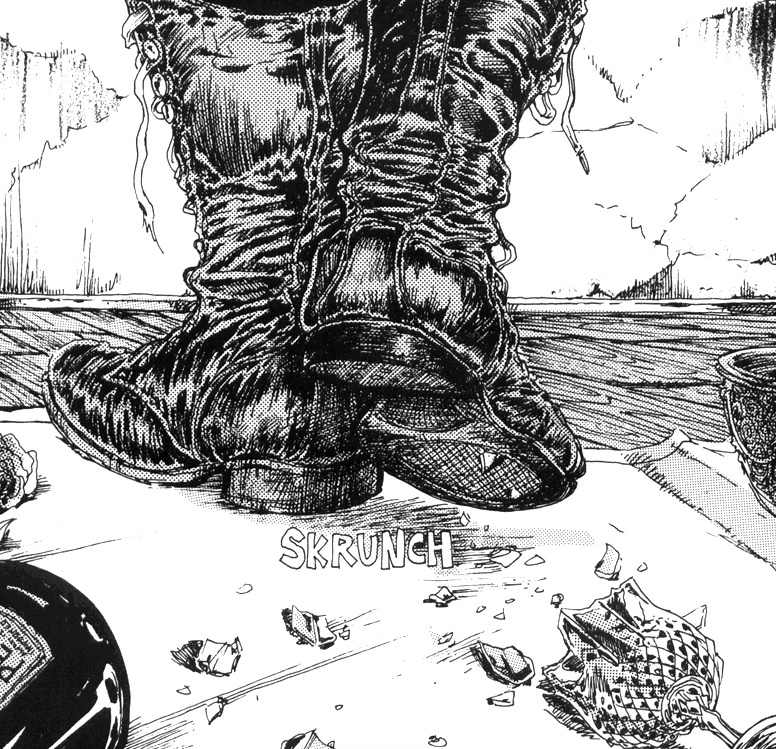

The author’s avatar is Eric, a slim, prickle-haired angel of goth conceived as combining the gaunt androgyny of Bauhaus vocalist Peter Murphy with the rippling physicality of Iggy Pop. Murdered by roving gangbangers along with his fiancé, Eric is guided back from the grave by a mysterious crow. In the watercolour flashbacks to his former life, he’s a rather sweet young man, until death grants him the tactical nous of a Navy Seal, as well as the undead’s traditional disregard for bullets. This Dante with a Remington 12-gauge hunts his killers through a hellscape Detroit, an alabaster harlequin with a rictus of black lipstick. He takes lives with maniacal flamboyance, announcing his presence with unnerving non-sequiturs (“I am the boiling man come to break the bones of your sins, meat puppet.”). He dances through the book like a crazed actor performing for whatever audience is applauding in his head.

He’s so compelling a creation none of the other characters manage to register. There’s Shelly (the murdered girlfriend), the indistinguishable mob of bastards who killed her, a little girl from the ghetto, and an overworked police captain trying to keep up. But they’re all phantoms next to Eric, whom O’Barr keeps centre-stage throughout, often isolating him, framing him like a performance artist. The artwork is fascinated by Eric’s tortured musculature, so contorted you can almost hear the sinews creak. In these moments, The Crow isn’t interested in advancing story beats or revealing character, as it is in abstract expressions of grief and rage. These pages weren’t drawn to entertain you; they were drawn for the author to scream into.

In this “temple to sadness” male pain is converted into violence. The real-life tragedy of a death by drunk-driving is reimagined as a premeditated ordeal of gang-rape, murder and worse. It’s upon this altar that the non-character of Shelly is sacrificed to motivate Eric’s vendetta. It’s the book’s ugliest conceit. Yet O’Barr is operating in such a raw and private vacuum that moral judgement feels intrusive. The Crow is so clearly a therapy piece, a dark yet safe space in which even the author’s meanest feelings may be expressed without censure.

However, The Crow is no longer a private work, along with all the movies and merch based upon it. Does this render it ‘problematic’?7 Well, that depends on your tolerance for graphic scenes of self-harm, sexual assault and gun violence, and whether you feel they count as valid expression or else a degrading force in the world. Whatever your view, The Crow is a work that demands to be processed on its own terms or not all.

A possibly redeeming factor is that the comic takes no pleasure in its own bloodshed. Though he shares Batman’s talent for terrorising evildoers, Eric is never venerated as a hero. The carnage he unleashes feels listless and squalid, often depicted off-panel or in claustrophobic asides. Action pages are staged more like the climax of Taxi Driver than a John Woo bullet-ballet. Headshots don’t take up entire splash pages. Exit wounds aren’t detonated in your face for shock value with every squirt of plasma artfully arranged. There’s no attempt to beautify. O’Barr dwells instead on morbid forensic details, like the way a man’s hair might catch fire if you shoot him in the back of the head at point-blank range. (O’Barr studied medicine in addition to his service in the marines.) The violence here is too real, too ugly, too rooted in human pain to be any fun.

There’s no mounting suspense as Eric hunts his prey, no agonising setbacks followed by glorious release. Of all Eric’s paranormal gifts – his speed, his ferocity, his grace – the one we feel most keenly is his ability to soak up bullets and tolerate agony. This is the Grim Reaper as janitor, revenge as a chore. “I’m eager to be done with this,” Eric says.

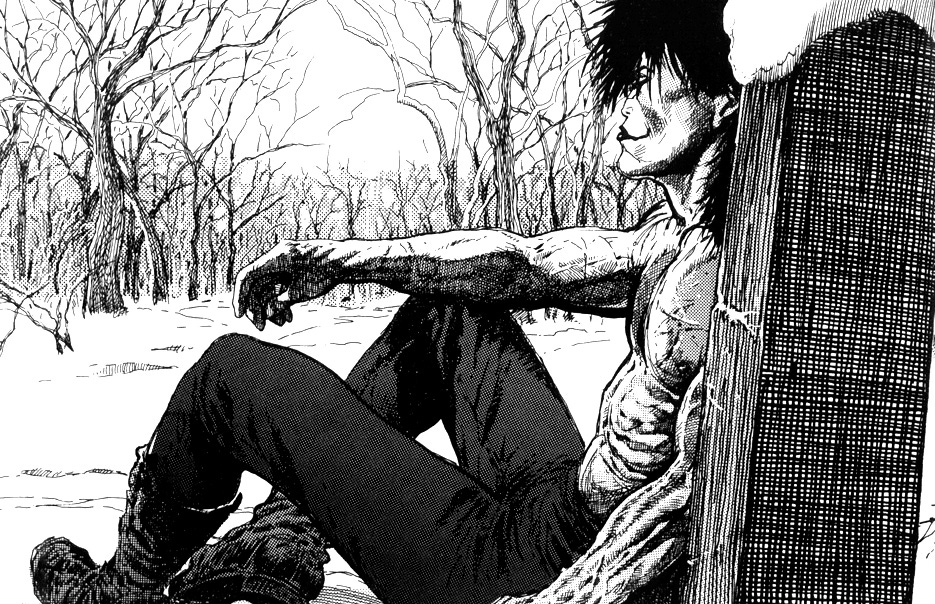

Sure, he throws down a few sick combat moves in the final show-down, taunting his adversaries by licking blood off the tip of his own nose. (“If anyone would like me to dial 911, please raise your hand.”) But by the time he’s done cleaning house, the sense of emotional desolation is palpable. The Final Boss dies unrepentant, and Eric has nothing left to do but curl up in the snow and die.

We don’t cut back to the other characters – to the little girl or the cop – and see how Eric’s rampage has made life any less excruciating for them. The city hasn’t been granted any measure of healing and Eric himself feels nothing but weariness. “It’s over,” he says. “I’m coming home.”

The Crow is not so much about revenge than it is about simply not wanting to be here, in this place, in this feeling. It’s not a story about coping with grief. It doesn’t articulate the experience of actually losing someone. It’s eye-of-the-hurricane stuff, raw and furious, yet surprisingly meditative.

Scattered with lyrics from British post-punk bands like Joy Division and The Cure, the comic reads like a concept album. It’s perhaps unsurprising that when the movie rights were picked up shortly after the comic’s publication, one producer wanted to turn it into a Michael Jackson music video.

Fortunately, Aussie director Alex Proyas came on board, along with star Brandon Lee (son of Bruce), a formidable martial artist and charismatic leading man in his own right, hoping for a breakout role.

The first adaptation of O’Barr’s book, The Crow (1994) was among the wave of comic-book movies that followed the success of Tim Burton’s Batman (89) and Batman Returns (92). Adapting lesser known (more affordable) properties, The Crow’s contemporaries include Steve Barron’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy (both 1990), Joe Johnston’s The Rocketeer (1991), Chuck Russell’s The Mask and Russell Mulcahy’s The Shadow (both 1994), Danny Cannon’s Judge Dredd and Rachel Talalay’s Tank Girl (both 1995).

Splatterpunk author David J. Schow was brought in to rewrite The Crow’s initial screenplay by cyberpunk author John Shirley, hot-rodding O’Barr’s brooding source-material with a rip-roaring exploitation plot and a substantial supporting cast. Loveable Ernie Hudson plays the sympathetic cop busted down from homicide for caring too much, alongside thirteen-year-old Rochelle Davis as the gravel-voiced skater girl who has befriended Eric and Shelly.

While the character of Shelly (Sofia Shinas) remains the same sacrificial angel she was in the comic, the bad guys become a more manageable, more memorable crew of street soldiers, mobsters and weirdos, among them leering scuzzbag David Patrick Kelly (creepy but making less of an impression here than he did in The Warriors), inquisitive, sharp-suited henchman Tony Todd, and Bai Ling as an incestuous witch with a thing for eyeballs.

At the top of this twisted criminal tree is a marvellously growly Michael Wincott (surely up there with James Earl Jones as one of the greatest, gravelliest voices in movies). He plays ‘Top Dollar’, a silken-haired kingpin with the fashion sense and drug habit of a regency duellist; though we’re never quite sure how he manages to retain criminal control over the city by burning it to the ground every year on ‘Devil’s Night’.

Eric becomes a rock guitarist and gets a surname – the suitability Poe-ish ‘Draven’. He also receives the postmortem gift of psychomancy, which lets him glean painful shreds of backstory by touching items and people connected to his former life – a handy exposition-tool neatly wielded as an impromptu weapon during the movie’s church-tower showdown.

Set in a gothic Detroit closer to the realistic Gotham of Matt Reeves’ The Batman (2022) than the art deco fairy-tale of the Burton movies, The Crow cleaves to the melancholy spirit of the source-comic, but has way less time for introspection. While the comic doesn’t welcome visitors, the movie rolls out the bloody-red carpet. This is a full-throttle revenge-o-rama that cordially invites the audience to relish the thrill of the hunt.

Proyas, then best known for his music videos, has a visceral feel for vibe and imagery, timing the action to a soundtrack full of prowling, pounding numbers like Burn by The Cure and Dead Souls by Nine Inch Nails. It’s when we share Eric’s righteous outrage that The Crow truly soars.

In a resoundingly gothic scene, Eric – having crawled out of his grave – returns to the ruins of the loft apartment in which he was murdered trying to protect his fiancée. Everything he touches electrifies him with flashbacks, memories jolting his dead body like Doctor Frankenstein turning up the juice on his creation. Fully charged with emotional voltage, Eric punches the mirror in fury.

It’s alive! It’s alive! And, boy, is it pissed!

Eric proceeds to build himself a monster out of greasepaint and stage leathers as lightning supercharges the sky. He poses by the window, his face revealed. Death is coming and we can’t wait to see the look on his victims’ faces.

Momentum builds as Eric swoops among the rainswept tenements, pinning his prey with their own throwing knives (“Somebody stuck his blades in all his major organs in alphabetical order.”), sticking them full of morphine or launching them off a pier in their car marinated in gasoline and dynamite. The movie understands the eternal pleasure of watching the bully get what’s coming to ‘em. It relishes their looks of helplessness, their hysterical denials. (“You can’t be you! There ‘ain’t no coming back!”) With his vampire pallor, Joker’s grin and Terminator relentlessness, Eric is an embodiment of gothic terror, only this time the monster’s on our side and we get to share his sadistic power. It’s an experience as morally questionable as it is exhilarating.

Brandon Lee…

He lost 20 pounds for the role, trained relentlessly, learned to play guitar, helped choreograph the fight scenes, did most of his own stunts, got a say in the script (successfully petitioning to remove a stereotypical Asian bad guy), and everybody loved him. Having demonstrated his chops in vigorous low-rent actioners Showdown in Little Tokyo (1991) and Rapid Fire (1992), The Crow would almost certainly have made Lee a mainstream star. But thanks to an improperly prepared firearm, Lee was accidentally shot and killed on set, while filming his own murder scene and two weeks away from marrying his own fiancée, Eliza Hutton. He was 28 years old.

Production stalled, though Proyas and most of the crew wanted to shut down permanently. Michael Massee – the actor who unwittingly fired the gun – was left traumatised, and James O’Barr wished he’d never written the damn comic in the first place - he later donated most of his movie royalties to charity. Lee’s fiancée and mother insisted the movie be finished, but Paramount were refusing to pay for reshoots. Miramax eventually stepped in to cover the rewrites, body doubles8 and VFX required to finish the movie without its star.

What footage remains of Brandon Lee in The Crow just about qualifies as a complete performance and - mercifully - it’s terrific. His Eric Draven is a magnetic presence, lithe and gleeful, full of gloomy swagger, wholly deserving of his status as a goth icon, though a macabre and sorrowful epitaph to Lee’s life and career.

From a comic book inspired by tragedy to a movie that ended in tragedy, the real-life poignancy of The Crow has been ill-served by the sequels9 and Funkos and Call of Duty skins that followed. Michael Wincott’s Top Dollar offers a prescient monologue in the movie…

“A man has an idea. The idea attracts others, like-minded. The idea expands. The idea becomes an institution…

“I started the first fires in this goddamn city. Before I knew it, every charlatan and shit-heel was imitating me. Do you know what they got now? Devil’s Night greeting cards. Isn’t that precious? Yeah.

“The idea has become the institution, boys.

“Time to move on.”

One wonders how James O’Barr must feel about all this, to have created a work so personal, so desperately authentic, and to watch that work run away from him and become a commercial entity, from therapy piece to meal ticket? And how much does this development shackle the creator to their trauma, to forever identify them with a work that represents the most painful years of their life?

The Crow’s original comic, its first movie adaptation, along with the tragedies that haunt them both, encourage moving on from trauma, not to fetishise it. Judging by the fan outcry over the 2024 Crow movie for even daring to be being made – let alone the mess it turned out to be – it seems audiences may feel the same way.

As any goth will tell you, a grave left undisturbed is all the more beautiful.

Stay weird.

“An essential critical guide.” Dreamwatch. “Recommended.” Choice. “Comprehensive… meticulously researched… richly illustrated.” Prehistoric Times

Available from Amazon, World of Books and publishers McFarland.

To find out more about me, my books, comics and other projects, click on my LinkTree

From Elfland to Poughkeepsie (essay, 1973)

In a YouTube video taken from A Profile of James O’Barr (2001), produced by Jennifer Peterson for The Crow DVD

For an extensive profile of O’Barr’s career, check out this three-part series of articles by indie comics historian ‘Sewer Mutant’ over on Medium

Issue 25, 1992. With thanks to Ben Willsher

Caliber never published issue five of the original run, so The Crow flew on to Tundra Comics, who reprinted the entire story as a prestige three-volume edition in 1992. The property pinballed around several publishers for the rest of the decade, including Kitchen Sink Press, London Night Studios and Image. It went out of print for a few years before Pocket Books re-released it in 2002, then IDW got hold of it and produced several spin-offs (including an X-Files crossover!). Crow stories are currently being published by Sumarian Comics

It’s notable that the 2024 movie starring Bill Skarsgård dispensed with the motivating sexual assault and at least attempted to portray Shelly as a character in her own right

One of them future John Wick director Chad Stahelski, a close friend of Lee’s

Three feature-film sequels: The Crow: City of Angels (Tim Pope, 1996, starring Vincent Perez and written by David S. Goyer), The Crow: Salvation (Bharat Nalluri, 2000, starring Eric Mabius, and Kirsten Dunst for some reason), The Crow: Wicked Prayer (Lance Mungia, 2005, in which someone thought it was a good idea to cast Edward Furlong in the role. Tara Reid, David Boreanaz and Dennis Hopper also appear in this stinker). A TV show: The Crow: Stairway to Heaven (1998-99), which ran for one season and starred Mark Dacascos. The property languished in development hell for years with threatened projects including Rob Zombie’s The Crow: 2037 (which would have been the third movie) and The Crow: Lazarus starring DMX (which would have been the fourth). Then there was the 2024 remake starring Bill Skarsgård, which The Guardian condemned as, “a total, head-in-hands disaster, incoherently plotted and sloppily made, destined to join the annals of the very worst and most pointless remakes ever made.”

What a fantastic essay! I read the original comics when I lived in NY - a friend of mine was a huge fan. The movie and the tragedy of Lee's death was very affecting at the time. The original movie had that 'lightning in a bottle' feeling, like the comic, and they rarely translate well into sequels or reboots unless the people in charge of the project stare deep into the bones of the work and reimagine it for this moment in time (but that requires them to not cynically think of it as another pull on the 'franchise/brand' slot machine).

Had no idea about the Crow comic. This was very informative and well written!