Who Goes There? (1938) vs The Thing (1982)

John W. Campbell's classic novella of Golden Age science fiction and John Carpenter's modern horror masterpiece - both absorb new meanings in the age of Covid, identity politics and generative AI

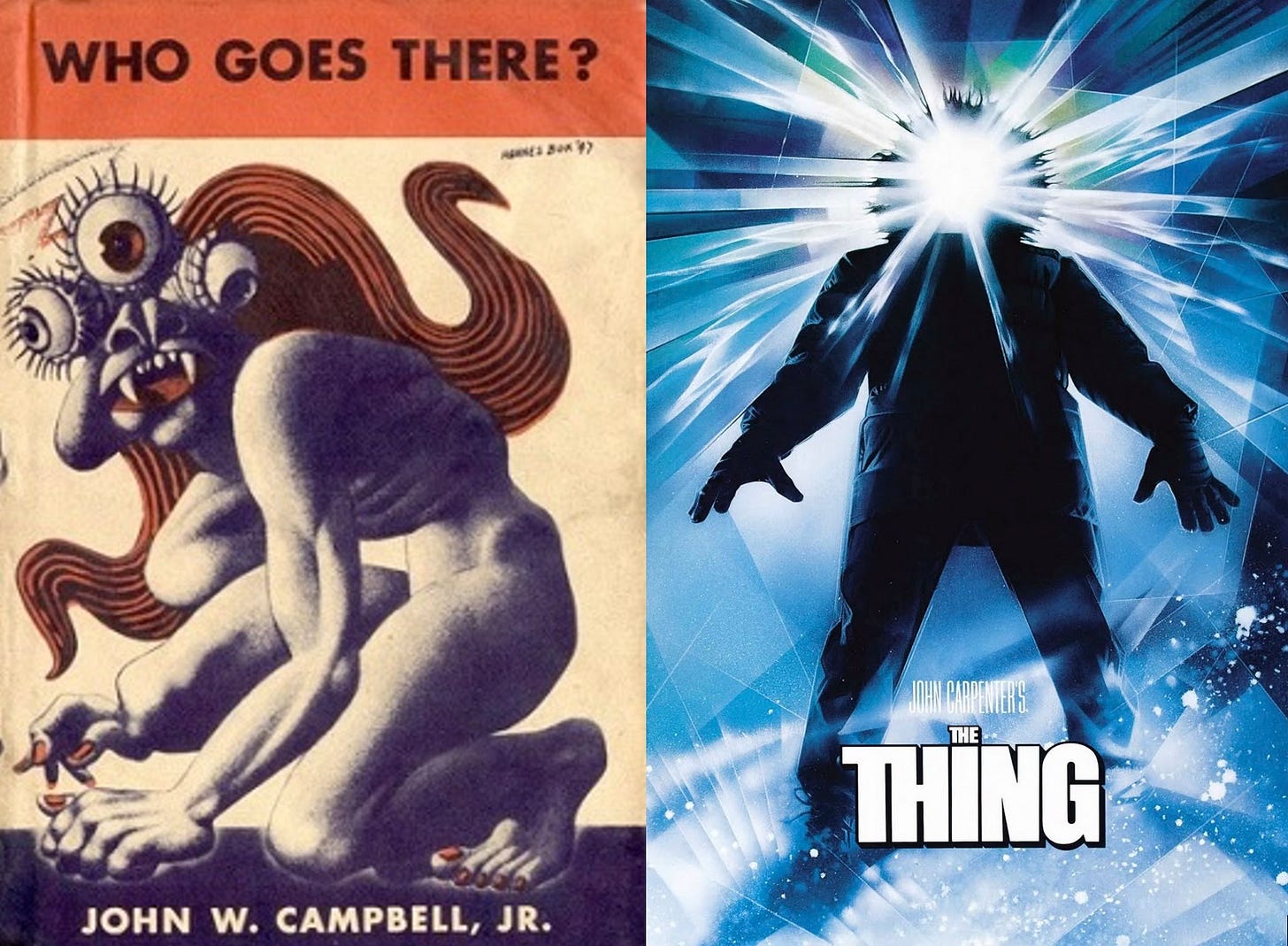

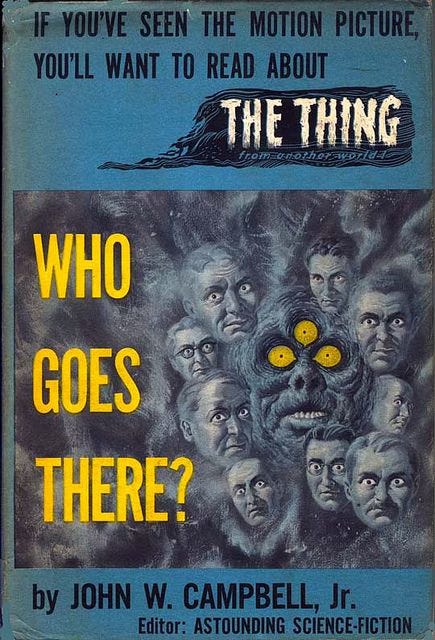

The classic sci-fi novella Who Goes There? by ‘controversial’ editor John W. Campbell has become something of a footnote next to the popularity of John Carpenter’s The Thing. Carpenter’s masterful 1982 movie has not only consumed Campbell’s 1938 story but replaced it in the public consciousness with an eerily perfect adaptation. It’s a cultural eclipse made all the more startling when you consider John W. Campbell is one of the most influential figures in 20th century American science fiction.

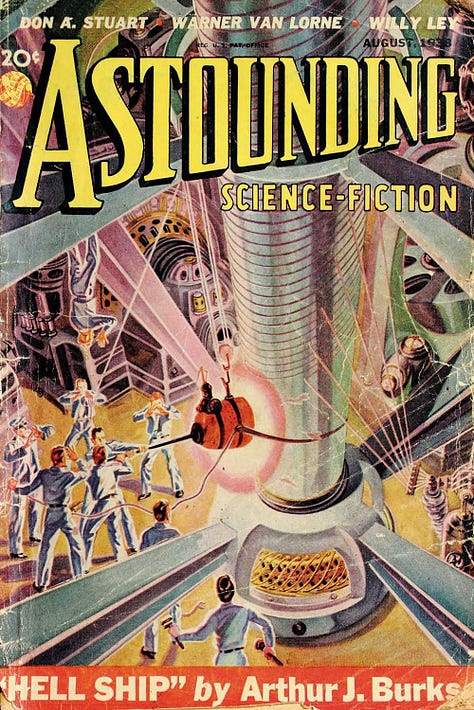

Campbell was in his late twenties with a respectable career as a sci-fi author by the time he took over editing Astounding Stories in December 1937. It was the dawn of the so-called Golden Age of Science Fiction, a period that lasted until roughly the end of the Second World War. He quickly re-titled the magazine Astounding Science-Fiction and set about moving the genre away from the gee-whiz Flash Gordonisms of previous years.

Campbell liked his sci-fi hard.

With war looming in Europe, he wanted the genre to ask how might science, technology and rational thinking save us from annihilation.

Under his stewardship, science fiction took a quantum leap in terms of ambition and quality, as Astounding launched the careers of Isaac Asimov1, Robert A. Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, A.E. van Vogt2, Lester del Rey3, and, yes, Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard.

In the age before paperbacks, Astounding fed the sci-fi fandom that had amassed within the letters pages of earlier pulps, a readership that was now maturing to find even greater meaning – even transcendence – in the genre they loved as kids.

Campbell retitled the magazine Analog in 1960, serialised Frank Herbert’s first Dune books from 1963, and managed to hold his own against classy competitors Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. He continued editing the magazine until his death in 19714.

John W. Campbell won more Hugos than I can be bothered to count and helped shape modern science fiction as we know it today: inventive, rigorous, thematic, humane, clairvoyant. He challenged intellectual dogma, was generous with his own fertile ideas, propelled by the righteous belief that science fiction could change the world.

However, Alec Nevala-Lee’s superb four-way biography, Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, reveals Campbell as a man exhaustingly provocative, certain of his own brilliance, overbearing in his opinions, an alpha nerd, an edgelord teetering on the precipice of his insecurities.

In a typically show-off move, Campbell published the apocalyptic short story Deadline in February 1944. Having studied atomic physics at MIT, Campbell fed author Cleve Cartmill technical details on the supposed composition of an atom bomb. Campbell’s guess was sufficiently educated to warrant both him and Cartmill a visit from Counterintelligence agents who suspected a leak on the Manhattan Project. It was a stunt that almost got Astounding shut down.

Campbell’s hankering for science-fictional ideas with real-world applications drove him increasingly onto the lunatic fringe. He went all in on L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics (the earliest form of Scientology), which Campbell was instrumental in developing. He championed several crackpot inventions, including a potentially fuel-free space drive and a machine he claimed could tune into psychic vibrations.

The so-called ‘New Wave’ broke upon the shores of Science Fiction in the 1960s, exploring softer, more humanist sciences, spearheaded by Michael Moorcock, J.G. Ballard, Harlan Ellison and Judith Merril. These experimental bohemians drew ideas from outside the sci-fi ghetto, a world that Campbell had built and from which he now refused to budge.

The pulps were no longer the final frontier. Gene Roddenberry’s original Star Trek (1966-69) was exploring strange new worlds of science fiction on television, seeking out new civilisations of mainstream fandom. The genre Campbell had formalised was rapidly outgrowing him. Instead of adapting, accepting that science fiction was bigger than just one man, he doubled-down.

His messianic fervour scared off both his wife and many regular writers, including Heinlein and Asimov, while his contrarian nature became ever more embittered and outspoken.

“By the early fifties Astounding had turned by almost anyone's standard into a crypto-fascist deeply philistine magazine pretending to intellectualism and offering idealistic kids an 'alternative' that was, of course, no alternative at all.”

Michael Moorcock, Starship Stormtroopers, 1977 essay

Campbell remained obsessed with the notion of the “competent [white] man”, the hands-on intellectual who might evolve into the Nietzschean Übermensch – the Chosen One who shall save us from the queers, negros, commies and feminists.

His editorials trolled the women’s movement, declared homosexuality a herald of cultural apocalypse, and suggested African-Americans might be better off under slavery.5

And, no, his prejudices were not “of their time”. They stemmed not from passive ignorance but conscious ideology, theories made all the more detestable for their purported rationality.

Campbell thought Samuel R. Delany was a brilliant writer but rejected his 1968 novel Nova on the grounds that Analog’s readership wouldn’t be able to identify with a Black protagonist. How much more profound and far-reaching might Campbell’s impact have been on his beloved genre had he broken the limits of his own biases.

We find the same paranoia in the algorithm-maddened fandoms of today, in online communities all over. We see those who allow an ideology to absorb them so completely that it becomes everything that they are. Anything that queries or objects to that ideology now becomes an existential threat, since the ideology in question is so inextricably tied to the person’s identity. Any challenge becomes potentially infectious, threatening to obliterate all they believe themselves to be. Everything outside the echo chamber becomes a chaos of probing, flailing, threatening ideas, a kaleidoscopic monster from which isolation provides the only protection. Considering any perspective outside your own must be resisted at all costs, in case it absorbs you, turns you into a thing that isn’t you.

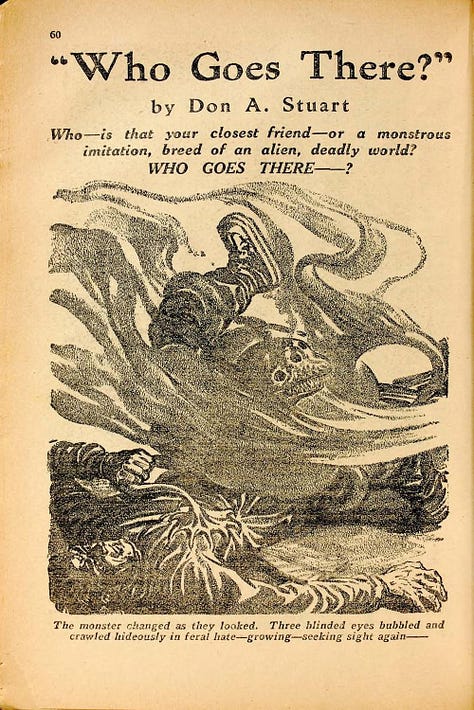

Campbell wrote Who Goes There? under his favoured pseudonym ‘Don A Stuart’6, published in the August 1938 edition of Astounding, shortly after Campbell took over as editor. It remains the story for which he’s best known, scoring a retro-Hugo award in 2014 for Best Novella7, as well as inspiring a record-breaking Kickstarter anthology of spin-off tales, Short Things, edited by the manager of Campbell’s literary estate, John Gregory Betancourt8.

Originally titled Frozen Hell, the novella likely borrowed its striking Antarctic setting from Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, which had been serialised in Astounding (née Astounding Stories) just two years ago in 1936. Campbell gives his polar research station plenty of authentic squalor and technical details, thoroughly researched from coverage of polar explorer Richard E. Byrd.

“The place stank. A queer, mingled stench that only the ice-buried cabins of an Antarctic camp know, compounded of reeking human sweat, and the heavy, fish-oil stench of melted seal blubber. An overtone of liniment combated the musty smell of sweat-and-snow drenched furs. The acrid odour of burnt cooking fat, and the animal, not unpleasant smell of dogs, diluted by time, hung in the air.”

The story is instantly familiar to anyone who’s seen the Carpenter movie, opening with a group of men standing around the reeking autopsy of an alien thing hacked out of the ice after a million-year power-nap. The men thaw it out (somewhat ill-advisedly) and the shapeshifting intruder makes an aborted attempt to absorb a kennel full of sled dogs. The resident pathologist has a violent freak-out and has to be locked inside his cabin. When it becomes clear the entire planet could become infected should the Thing reach civilisation, the men become paranoid and devise a clinical test that will determine who among them might be hiding tentacles under his cable-knit sweater.

“McReady heated the platinum wire in the alcohol lamp flame, then dipped it into the tube. It hissed softly. […] ‘Human, I’d say,’ McReady sighed.”

The names are familiar too: McReady, Blair, Norris, Dr Copper, Commander Garry, dog-handler Clark. Though Campbell’s characters are uniform he-men of science, action nerds prone to reams of ‘as you know’ exposition, competent men to a man.

McReady is essentially Doc Savage in an orange parka, more Jack Reacher than Kurt Russell. Campbell adores him.

“Moving from the smoke-blued background, McReady was a figure from some forgotten myth, a looming, bronze statue that held life, and walked. Six feet four inches he stood as he halted beside the table, and with a characteristic glance upwards to assure himself of room under the low ceiling beams, straightened. His rough, clashingly orange windproof jacket he still had on, yet on his huge frame it did not seem misplaced. Even here, four feet beneath the drift-wind that droned across the Antarctic waste above the ceiling, the cold of the frozen continent leaked in, and gave meaning to the harshness of the man. And he was bronze – his great red-bronze beard, the heavy hair that matched it. The gnarled, corded hands gripping, relaxing, gripping and relaxing on the table planks were bronze. Even the deep-sunken eyes beneath heavy brows were bronzed.”

Unlike the flailing, crawling appendage-salad concocted in latex and KY by the mad genius of special effects legend Rob Bottin, Campbell’s thing assumes a signature form. It’s a hateful Medusa with three blood-red eyes, electric-blue worms forming a writhing hairdo.

Campbell based the monster on his mother.

Dorothy Campbell was a domineering parent prone to violent, mercurial moods, who threatened to extinguish the self-assured, competent man Campbell yearned to become. She also had an identical twin. As a child, Campbell would rush home from school to embrace his mother, only to find himself pushed away by an icy doppelganger.

Campbell strives to make his story feel science-forward and authentic, as far away from the ray guns and romance of Buck Rogers as he could get. But the result often feels over-detailed, over-rationalised and pedantic. His prose is stilted, his characters little more than an indistinguishable debate club, with dialogue that can sound like it should be headlining a trailer for Invasion of the Saucer Men.

“’Nothing Earth ever spawned had the unutterable sublimation of devastating wrath that thing let loose in its face when it looked around its frozen desolation twenty million years ago. Mad? It was mad clear through – searing, blistering mad!’”

But the concept of Who Goes There? remains brilliant. As a vehicle for suspense, it’s perfect, as stark and merciless as its snowbound setting. Ironically, the novella feels at its best when it plays to its pulpy core instead of fussing over the latest passivating processes that go into making acid-resistant magnesium alloy.

Campbell’s writing really kicks into gear when he focuses on action and atmosphere.

“A drift wind was sweeping by overhead. Right now the snow picked up by the mumbling wind fled in level, blinding lines across the face of the buried camp. If a man stepped out of the tunnels that connected each of the camp buildings beneath the surface, he’d be lost in ten paces. Out there, the slim, black finger of the radio mast lifted 300 feet into the air, and at its peak was the clear night sky. A sky of thin, whining wind rushing steadily from beyond to another beyond under the licking, curling mantle of the aurora.”

Unlike the home-ground advantage afforded by the hidey-holes and peek-a-boo spots that riddle the Nostromo, Crystal Lake or the Overlook Hotel, Campbell’s Antarctica is a setting lethal to man and monster alike.

“At the surface – it was white death. Death of a needle-fingered cold driven before the wind, sucking heat from any warm thing. Cold – and white mist of endless, everlasting drift, the fine, fine particles of licking snow that obscured all things. […] It was easy for any man – or thing – to get lost in ten paces.”

Skip the next few paragraphs if you’re troubled by spoilers for the book…

Campbell’s ending is as optimistic as Carpenter’s is famously downbeat.

Having narrowly managed to torch the Thing, the survivors discover an anti-gravity backpack and atomic generator, which the alien had cobbled together in its shack to reach America and from there take over the world. The monster is dead. The supremacy of the competent man is confirmed, his galactic backyard successfully defended.

Yet the story ends on a mingled note of awe and terror as the survivors realise how the Thing was smart enough to build a means of escape using nothing but “coffee-tins and radio parts, and glass and the machine shop at night. And a week – a whole week – all to itself.” In the end, it was the creature’s advanced intelligence that posed the most decisive threat.

It’s Campbell’s worldview in a nutshell: IQ prized above all, brainpower as superpower. If intellect is a force strong enough to threaten civilisation, it might just as easily save it.

Campbell may have been dismayed to find his optimism wasn’t shared by the movies that adapted his work.

Sci-fi historian Bill Warren speculates9 that it may have been author and screenwriter Leigh Brackett who brought Who Goes There? to the attention of Howard Hawks. She was certainly grateful to Campbell for the early break he’d given her as a pulp writer before they parted ways and she went on to co-write Hawks’ The Big Sleep (1946)10.

The Thing From Another World (1951) is crisply directed by Christian Nyby, Hawks’ editor on The Big Sleep (1946) and Red River (1948)11. With a decent budget of $1.5 million, it was a major film that dared take its sci-fi seriously. Along with The Day the Earth Stood Still (released later that year) and George Pal’s double-whammy of Destination Moon (1950, co-written by Robert A. Heinlein) and When Worlds Collide (1951), The Thing was a landmark picture that helped bring science fiction into the mainstream. Heavily publicised, it kept its monster under wraps, much like the marketing for Predator (1987) and Nosferatu (2024) decades later.

The result is classy but conventional, the monster reduced to a standard Karloffian brute (played by James Arness of TV’s Gunsmoke) wisely kept to the shadows (aside from a still-great jump-scare). Campbell’s concept of the alien shapeshifter is dropped, replaced with the idea of a bloodsucking humanoid vegetable. (“An intellectual carrot! The mind boggles!”) Perhaps a distant cousin of Audrey II from Little Shop of Horrors, this Thing spawns a tray of pulsating saplings that wail like hungry newborns through a doctor’s stethoscope.

The paranoia angle went too, the movie focusing instead on the tension between the Air Force jocks (led by a horny Kenneth Tobey) and the pipe-puffing boffins (led by Robert Cornthwaite in blazer and turtleneck), while the visiting newshound (Douglas Spencer) hustles for the scoop. The misguided eggheads try and reason with the beast and get a backhand for their troubles, while the flyboys – who know all too well the horrors science wrought upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki – are happy to risk a court martial by frying the Thing into oblivion.

PROFESSOR CARRINGTON: “You’re robbing science of the greatest secret that’s ever come to us! Knowledge is more important than life, Captain. We’ve only one excuse for existing, to think, to find out, to learn… We’ve thought our way into nature. We’ve split the atom!”

CYNICAL FLYBOY: “Yeah, and that sure made the world happy, didn’t it?”

The Hawksian banter is cool, but there’s little tension. Everyone’s too full of wisecracks, the men too damn competent for the invading Thing to feel much more than an inconvenient guest.

The Hawks movie had been held in high critical regard for thirty years, fuelling antipathy towards any ‘remake’, though Carpenter was really making a closer adaptation of the original novella.

Released in 1982 to underwhelming box-office12, the movie faced the flamethrowers of critics and sci-fi authors alike. Pauline Kael called it, “a film of limited imagination with unlimited horror effects… Carpenter seems indifferent to whether we can tell the characters apart; he apparently just wants us to watch the apocalyptic devastation.” Harlan Ellison raged in his column for LA Weekly, “The Thing did not need to be remade, if the best this fearfully limited director could bring forth was a rip-off of Alien in the frozen tundra, this pointless, dehumanised freeway smash-up of grisly special effects dreck, flensed of all characterisation, philosophy, subtext or rationality.”13

Carpenter’s Thing scurried into cultural purgatory where it remained frozen and forgotten. Ten years later, movie-hound Quentin Tarantino cited it as a major influence on his groundbreaking Reservoir Dogs (1992). The British Film Institute canonised Carpenter’s movie as a BFI Classic in 1997 with an excellent monograph by Anne Bilson. The generation of monster fans – Tarantino among them – who had already discovered The Thing on VHS were now finding each other on the internet, building the famous fansite Outpost #31. These days, John Carpenter’s The Thing is a staple of alt-movie posters and YouTube reaction videos.

Carpenter returns to the suspense and paranoia that made Campbell’s novella so effective. Texas Chain Saw Massacre director Tobe Hooper wrote an early draft of the script and Bill Lancaster (son of Burt) wrote the last. The finished screenplay shares 80% of its DNA with Campbell’s source novella, the remaining 20% nothing but improvement.

The cast is reduced from 32 to a more manageable 12 angry, paranoid men. No longer uniformly competent, the boys are diversified as irritable, gruff, introverted, Black, podgy, funny, and – in one case – very, very high. Everyone gets just enough personality for you to wince when they dissolve into screeching protein-taffy.

Among the all-male cast – as Anne Bilson points out – the Thing itself is the monstrous feminine, as in Campbell’s original.

Our focal hero MacReady (Kurt Russell on fine laconic form) is no longer a hulking meteorologist, but a growling chopper pilot with a mean hangover. (“First goddamn week of winter.”)

Carpenter had already established Russell’s action credentials as the one-eyed Eastwoodian stud of Escape From New York (1981). Again, we find Russell lantern-jawed and scowling from under that shimmering chestnut mane, though an early scene of MacReady playing computer chess establishes him as a thinking man, a strategist, albeit one who’d rather blow everything up than lose a single game.

Filmed on location in glacial British Columbia14, the movie tops and tails Campbell’s story quite brilliantly. The opening scene nails you from the get-go, prickling you with questions. Why is that helicopter chasing a Huskey across the ice? Why are these Norwegian jerks trying to shoot the poor doggie? Why are these guys so scared? What the hell got us here? Why is their chopper loaded with kerosene? What are they planning to do? We soon find out, establishing what’s at stake for the men of Outpost #31 as they battle to avoid the same horrific fate.

Then there’s the ending. It’s one of the most perfect in all cinema, up there with Charles Foster Kane’s ‘Rosebud’ and Charlton Heston howling at the Statue of Liberty.

In creating his monster, Carpenter wanted to avoid the guy-in-the-suit solution he’d seen in Alien (1979) and all those flying saucer movies he’d seen as a kid.

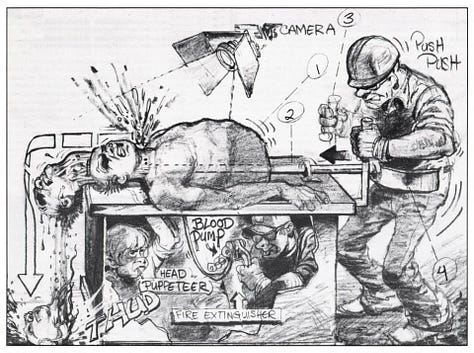

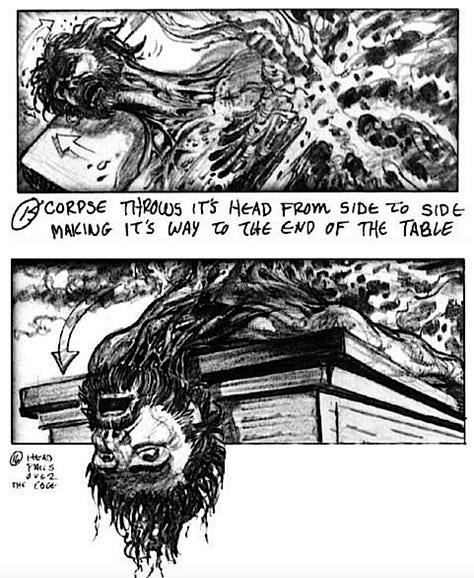

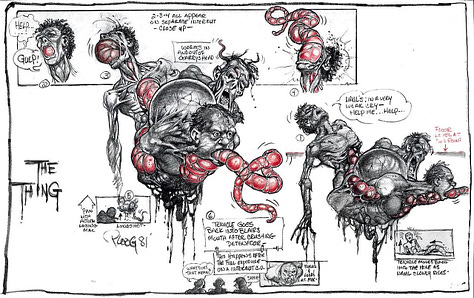

Special effects god Rob Bottin was 22 at the time, a rabid fan of Carpenter’s Halloween, and who had previously wrangled himself a makeup job on The Fog (1980)15. Bottin had some wild ideas about returning to Campbell’s original concept of an alien comprised of every lifeform it had ingested on its tour of the galaxy. He took his concepts to Marvel-artist-turned-storyboarder Mike Ploog16.

Heading a crew of over thirty creative technicians, Bottin ended up living on the interior set at Universal Studios for an entire year, working seven days a week, at one point causing a fireball to engulf the stage from a brew of toxic chemicals used during the defibrillator scene, and finally became hospitalised with exhaustion.

Bottin’s flesh-twisting showstoppers (“You gotta be fuckin’ kidding!”) get all the attention and remain unforgettable – marvellous feats of craft and imagination, mesmerising, alarming, tangible, inspiring – but it’s the smaller, half-glimpsed weirdness that works just as well: the arterial rivulets frozen to icicles on a dead man’s wrist; the anguished face parted like strings of melted mozzarella on the coroner’s table; the victim dragged away by his own liquefied face; the blank-eyed scientist raising dripping, misshapen claws, caught in the intimacy of his own transformation, howls in outrage at his executioners. Half-seen, these passing horrors all build the movie’s monster-ridden premise without you even realising.

The big scenes would feel adrift and gimmicky without them.

“The thing we found was part Charnauk [the dog], queerly only half-dead, part Charnauk half-digested by the jelly-like protoplasm of that creature, and part the remains of the thing we originally found, sort of melted down to the basic protoplasm.” […] “It digested Charnauk, and as it digested, studied every cell of his tissues, and shaped its own cells to imitate them exactly. Part of it – parts that had time to finish changing – are dog-cells. But they don’t have dog-cell nuclei.” Blair lifted a fraction of the tarpaulin. A torn dog’s leg, with stiff grey fur protruded. “That, for instance, isn’t dog at all; it’s imitation.”

Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell, 1938

Like many Lovecraft stories, Campbell’s source novella wins on concept rather than craft; Carpenter’s movie has both.

By 1982 the director was famed for his taut brilliance and works his widescreen frame with typically Hawksian precision, keeping you off-kilter, watching every conspicuously unoccupied space, fearing the shadows. There are fans out there who say they’ve figured out who infected who and when, but the movie puts the squeeze on us so efficiently that most of us are happy to take it on trust.

Carpenter knows that breaking things down like Agatha Christie would only diminish the mood.

Like all Carpenter’s movies, The Thing is unpretentious. Carpenter doesn’t work to a complex intellectual thesis like genre contemporaries David Cronenberg or Wes Craven. His movies are primarily exercises in storytelling. He’s not blind to his themes17; he just works them from the gut. Paradoxically, it’s Carpenter’s refusal to give The Thing any definite intellectual shape that opens the movie up to all manner of readings.

Watching the men ponder global infection rates while locked away in their cabins feels unnervingly familiar post-Covid.

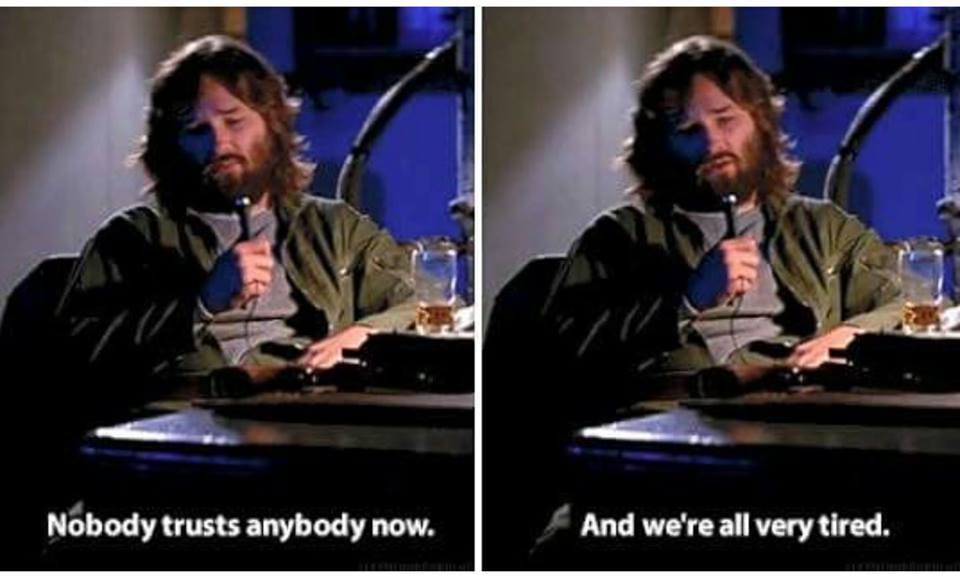

“Trust is a tough thing to come by these days,” says MacReady. Indeed it is. Who today can look at their neighbour and not wonder whether they might cast the vote or harbour the opinion that will blow up your world. MacReady’s lament, “Nobody trusts anybody now – We’re all very tired” has become so depressingly relatable it’s now a meme.

Unscrupulous tech bros direct AI programs like Things digitised, ravenous databases working in the shadows, snaring and absorbing the soul of humanity, replacing authentic creativity with uncanny imitation, art - a pinnacle of human endeavour - reduced to mathematical currency.

Eleven of my own books currently count among the estimated 7.5 million stolen by pirated-book database LibGen, pilfered in turn by Zuckerberg’s Meta and other companies to train their AI systems. My fellow writers and I are left feeling like MacReady, itching to fling a stick of dynamite in the face of overwhelming greed.

“McReady’s great, bronze beard ruffled in a grim smile. ‘This is satisfying, in a way. I’m pretty sure we humans still outnumber you – others. Others standing here. And we have what you, your other-world race, evidently doesn’t. Not an imitated, but a bred-in-the-bone instinct, a driving, unquenchable fire that’s genuine. We’ll fight, fight with a ferocity you may attempt to imitate, but you’ll never equal! We’re human. We’re real. You’re imitations, false to the core of your every cell.’”

Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell, 1938

Campbell and Carpenter share not only the same vision of the apocalypse, one in which humanity can be rendered into protean slurry, but also the same sense of defiance, of hope in the face of horror.

Campbell’s competent men endured their frozen hell, but in doing so realised the vast potential of the human intellect. Carpenter’s MacReady may be morose, petulant, self-destructive, but his flaws become survival traits, signifiers of humanity, value in a perfectly inauthentic world.

Stay weird.

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

As well as publishing Asimov’s groundbreaking short Nightfall (1941), Campbell also helped build the lore behind the Foundation stories, as well as define Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics.

Campbell published van Vogt’s proto-Alien tale Black Destroyer in 1939 and serialised his first novel Slan (1946). Fanboys identified so strongly with this latter story about a race of persecuted supermen that they coined the phrase, “Fans are Slans”.

Del Rey would go on to become an editor himself at Ballantine where he changed the course of mass-market fantasy in the late 1970s.

He was replaced as editor by Ben Bova.

His private letters were even worse.

In honour of his wife Doña, who was also his typist, copy editor, beta reader and sounding board.

It’s doubtful the novella would have received that accolade after 2019, when the memorial John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer was hastily renamed the Astounding Award after winner Jeanette Ng denounced Campbell as a fascist in her acceptance speech.

The Short Things project began with the unearthing of several unfinished Campbell manuscripts by biographer Alec Nevala-Lee, among them drafts of the story that would become Who Goes There?

In his book Keep Watching the Skies! (McFarland, 2010)

Her final screenplay was an early draft of The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Debate persists over who really directed the picture. Nyby was after his directors’ union accreditation and producer Hawks was happy to throw him a project. According to interviews with the cast, Hawks maintained a strong advisory presence on set and the movie certainly bears many of his directorial hallmarks. According to Nevala-Lee’s Astounding, Hawks pocketed the lion’s share of the director’s fee.

It was undoubtedly steamrollered by the success of E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, which had opened in the US two weeks before.

People felt much the same way about the 2011 prequel starring Mary Elizabeth Winstead. Ellison’s LA Weekly columns are collected in An Edge in My Voice (1985).

They built the sets in summer then waited for it to get buried in the winter snow. The interiors were shot on temperature-controlled sets on the Universal lot during a particularly scorching LA summer. The flu germs had a field day, apparently. (Terror Takes Shape, a 1998 Thing documentary by Michael Matessino.

Standing around 6’5, Bottin also donned glowing red eyes and seaweed as the ghostly sea-dog who draws his cutlass at the end of the picture.

Having worked on spooky titles like Ghost Rider and Werewolf By Night throughout the ‘70s, Ploog had recently left Marvel after a disagreement with Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter. He storyboarded/designed for Wizards (1977), The Lord of the Rings (1978), The Dark Crystal (1982), Ghostbusters (1984) and more.

Check out his even-more paranoid sci-fi They Live, 1988.

Blimey, this is mammoth!

Incredible article! Well done.