We Need To Stop Being Weird About Theme in Stories

What your story is really saying and why you need to stop saying it

Stories don’t mean shit without theme.

Theme is what your story is really about, beneath all the starfighter battles, lovelorn androids, and moody wanderers jabbing fools with a broadsword. It’s the writer’s emotional and/or intellectual connection to the material. It’s how they feel about the characters and what they’re up to. If the writer can’t connect to a story, the reader can’t connect either. If the writer is bored or just typing their way to an invoice, that apathy will stink up the page like a kipper under the floorboards.

Moby Dick is a novel about the tragedy of pride, but Melville doesn’t state that theme out loud.

“Avast!” growled Ahab. “A feeling burns in mine breast that this yarn be about the dangers of the unchecked male ego and the brute indifference of nature. Stow the subtext, Mister Starbuck! To perdition’s flame with reader involvement! We seek the white whale of the bleedin’ obvious!”

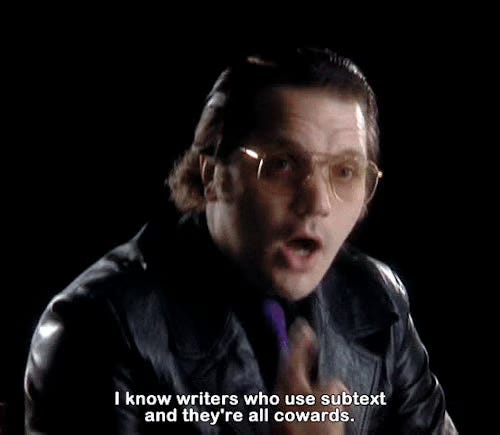

Theme is exposition and as such requires a decent burial.

Theme, along with details like where the butler was when Lord Swankington got shivved with a dessert spoon or the fact that your heroine is really, really, really good at kicking people in the head, all this stuff starts out as info awaiting a dump. It’s leaden story-data that must be spun by the process of your writerly imagination into the gold of characters that live and scenes that stir the soul.

Writers lacking skill in this kind of alchemy tend to bullhorn their themes like they’re on a protest march. Or – bless them – they’ll try and educate us like we’ve been dragged into the principal’s office.

This isn’t storytelling; it’s editorial.

Storytellers seeking to confront the reader with a direct message often forget that the reader most in need of hearing that message is usually the one who will clap their hands over their ears and go ‘LALALALALALALA!’

This is just part of our weird modern relationship with theme in stories, certainly as I’ve experienced it writing comics.

I’ve gotten into the habit of always writing to a unifying theme. Doing so provides a sort of compass that helps me navigate how best to put the story together. Would a wintery setting better convey my theme of isolation? What kind of end-boss monster would best embody the hero’s thematic struggle to emerge from his father’s shadow?

As Pixar writer-director Andrew Stanton says, “Theme dictates every decision.”1

Theme also revs my passion-engine. It keeps me excited about the project in hand and stops me flagging if I’m writing over the course of several months. I have to find something in the characters to which I can relate or which I find fascinating, even if that character is a sentient ameboid from the Garvlaxx Cluster or an amoral bastard who punches kittens for a living.

As another Pixar alumni put it, storyboard artist Emma Coats, “Why must you tell this story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.”

Or as I’d put it, “Theme: what’s in it for you?”

When I wrote The Last of Her Kind (2024) for 2000 AD, my first continuation of Hawk the Slayer, I wanted to write a story about the dangers of nostalgia. My Judge Anderson script Hell-Night at the Cine-Pit (2025) is a supernatural take on AI, how human creativity has been rendered into soulless, protean sludge. I’ve just finished the script on my next Durham Red adventure, a neo-noir called Hungry City, and it’s all about the cost of personal freedom and how it feels to be treated like a commodity.

All very grown-up stuff expressed through the kind of pulpy adolescent nonsense I adore: blokes with swords beating up monsters, women who can make your head explode just by thinking about it, and vampire antiheroes struggling to maintain a moral compass while getting a kick out of eating people.

But I don’t wield these themes like I’m attacking a mob of zombies with a baseball bat. The readers (fingers crossed, I have more than one) have paid a fiver to experience a rush of thrill-power, not a lecture on ethics. So I’ll cut any lines of dialogue I feel are too on-the-nose and dial down any too-obvious symbolism.

The more I tell the reader what to think, the more I bully them out of the picture.

Besides, readers can’t be told what to think or feel.

“[Readers] don’t so much read as respond. They do not automatically adopt your outlook and outrage. They formulate their own. You are not the author of what readers feel, just the provocateur of those feelings. You may curate your characters’ experiences and put them on display, but the exhibit’s meaning is different in thousands of ways for thousands of different museum visitors, your readers.”

Donald Maass, The Emotional Craft of Fiction (2016)

In other words, it’s not all about you, the writer.

Even authors at their most didactic – Dickens in Hard Times, Orwell in 1984, Miller in The Crucible, Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale – still express their allegorical stories through drama and character.

They explore their themes rather than simplify them. They open an imaginative space in which the reader can respond, inviting them to partake in a tango between author and reader that transcends mere words on a page.

Morals are the currency of fable, not great drama.

Morals are themes that have been condensed and simplified, which is why they’re often deployed for the benefit of children. They’re broad statements that brook no argument. Their tone is parental.

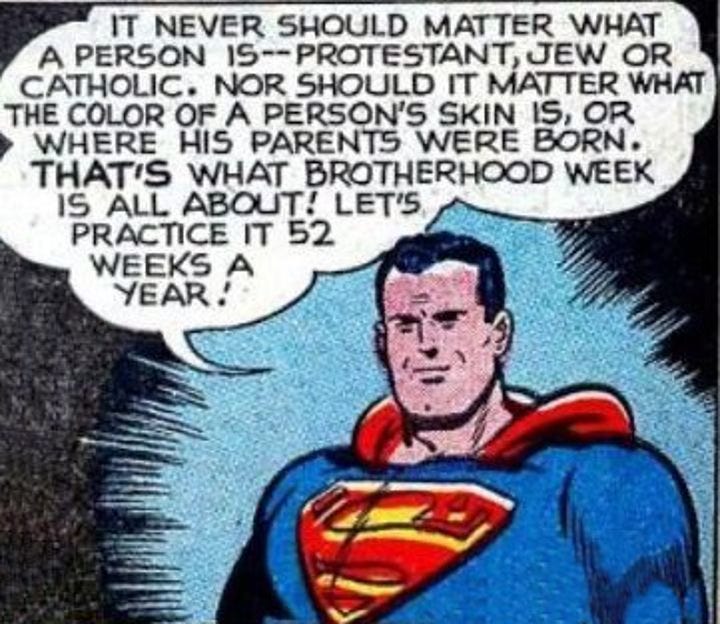

The tedious accusation that comics – that is, North American superhero comics – have become ‘too political’ is often just a case of a writer being too heavy-handed when it comes to theme.

Yes, superheroes have always been political. When Captain America first kapowed Hitler back in 1940 he was – and remains – an embodiment of social justice. That said, writing for the moral edification of children and servicemen 85 years ago is very different from writing for the media-savvy adult of today. A superhero can’t just mouthpiece a story’s theme without coming across like a primary school teacher or a drill sergeant.

Whenever I come across a soapbox monologue in a superhero book – that panel when the hero gets an earnest close-up or strikes a pose while delivering heaps of dialogue baldly stating how the writer feels about the world – I almost always agree with the sentiments expressed, as do the readership at which the monologue is clearly aimed.

Sooooo, what’s the point of the monologue?

Is the writer looking to inspire a thought or feeling other than complete and redundant agreement?

Monologues are fine, but they need to be filtered through the character’s perspective. A writer can’t just slam on the story-brakes and deliver an impassioned social media update using their main character as a textbox.

Comics like Judge Dredd: A Better World (by Rob Williams, Arthur Wyatt, Henry Flint, Boo Cook and Jake Lynch) or the Dredd prequel series Dreadnoughts (by Michael Carroll and John Higgins) do the hard work of dramatising, deepening and diversifying a conversation about the limits of policing. They don’t arrest the reader with a moral lesson demanding compliance, but rather offer a theme which the reader can explore and engage.

Given the current storm of social injustice, so much of it unprecedented in its shamelessness, readers really can’t be blamed for demanding stories not only say something about the world but scream it out loud.

Readers want to know they’re not alone in their outrage.

But as with the novels of Dickens and Atwood, that zeal must be tempered with craft if it’s going to do more than just add another echo to the chamber. After all, to engage thought and feeling and our common humanity is the real work of changing minds.

The problem we’ve got is that theme has become a commodity.

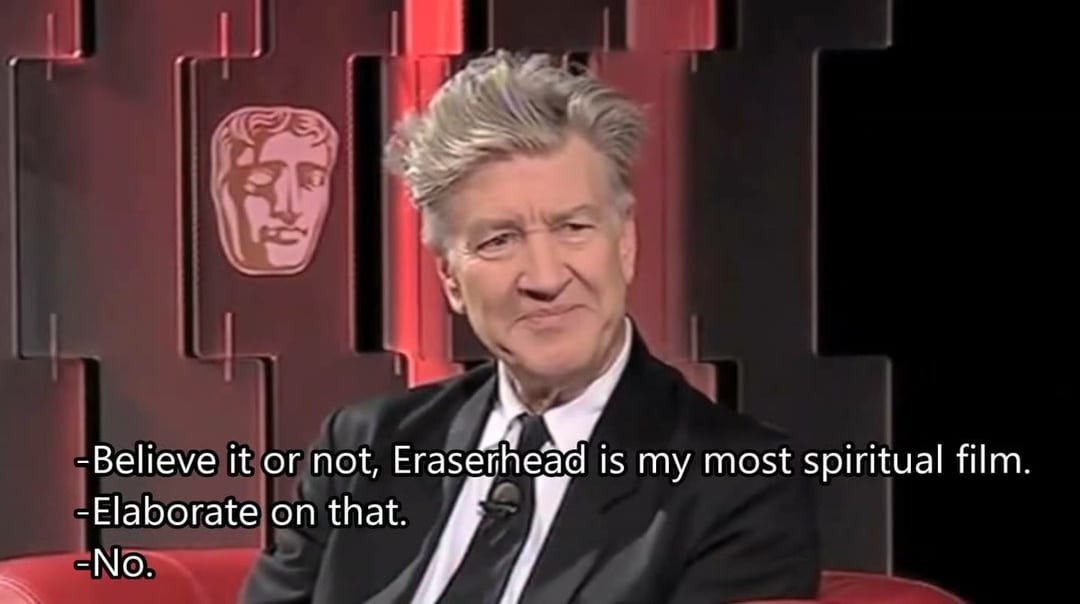

Take ‘elevated horror’.

Whoever came up with that term deserves a slap, though it seems to have arisen from a genuine need to articulate the impact made on the horror genre by arthouse studio A24. Launching in 2012 with a keen focus on digital marketing and social media, A24 has launched the career of at least one electrifying horror auteur, Robert Eggers (The Witch, 2015; The Lighthouse, 2019; Nosferatu, 2024).2

These movies, together with other ‘elevated horror’ movies from other studios, like David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014), Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook (2014) and Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) – all brilliant films – are distinguished by their overt social commentary or else a certain artiness that announces hidden meaning, promising something more than just gore and jump-scares.

These movies’ themes are a major part of what is supposed to ‘elevate’ them above mere entertainment like your average Conjuring sequel. In terms of branding, ‘elevated horror’ is eminently sellable. Discussion of these movies will make you look tasteful and clever. Championing their social commentary will rate you highly on the virtue index. It’ll score you likes and subscribes and fuel the contradictory outrage economy.

Thus, theme becomes currency.

I’m too close to my own stories to always make an accurate judgement as to whether I’m being too cryptic or too obvious when it comes to theme. I mainly write pulpy genre comics (I don’t have enough money in the bank right now to take time out and write much else), but I’m always confident my theme will be there to greet the reader should they ever pause to look for it.

Thing is, the reader never seems to pause to look for it.

My Ego emerges from his bower and snarls about readers failing to recognise my undoubted genius. He bellows like Withnail on the heath…

My Ego also gets very annoyed when it comes to reviews. On the rare occasion my work warrants commentary, the theme goes unnoticed 99% of the time.

Which is ffffffffffine (Alec writes through gritted teeth).

Despite the badgering of my Ego, I know my themes aren’t there to grab attention, but to guide the building of my story, to express how I feel about myself and the world and hopefully inspire reflection.

Readers and reviewers assuming my daft adventure comics have nothing to say is one thing, but the accompanying value judgements are another.

The word “silly” often comes up in comments about my stories, along with “shallow”, “disposable” and “simple enough”. The general feeling is that the stories are competent and fun, but certainly not ‘elevated’.

When I read commentary on other creators’ comics, I get the feeling readers and critics don’t tend to look for deeper meaning unless the theme or social commentary is somehow advertising itself.

This eat-your-greens approach can be hazardous to one’s storytelling, but it’s the approach that will usually get a writer noticed, get your work shared and promoted, talked about, whether it’s being castigated by comicsgate conmen or complimented by the critics.

Theme says you’re a serious, valuable writer. Theme gets you in the right drinking circles and scores you more work.

The writer must therefore be seen to be saying something or else risk irrelevance in the marketplace. Worse still, a seeming refusal to state your theme out loud might risk accusation of your harbouring malevolent intent. Amid such paranoia, it’s understandable that a writer may wish to take no chances and announce their theme in neon letters big enough to be read from inside a cupboard buried on the dark side of Neptune.

We don’t need an episode of Black Mirror to tell us that readers and audiences are less engaged these days. Last year Yanna Lina, a Booktokker with 2.7m+ followers, complained in a since-deleted post that Leigh Bardugo’s fantasy novel Six of Crows contained too much writing. (“Why are the pages so filled with so many words? Like, what the f***?”)

Writing for N+1 magazine, journalist Will Tavlin revealed that Netflix are encouraging their screenwriters to have characters announce what they’re doing while they’re doing it, so that viewers at home can still follow the story while scrolling on their phones.

As with theme-loud storytelling, virality has become more important than writing that actually, quietly engages.

Writers then find themselves caught between what is needed to write well and what is needed to get that writing under readers’ noses. The story needs you to bury (that is, dramatize) your theme, but the attention economy – and your long-term career – would prefer you announce it.

Publicists favour writers who are already self-promoting. Need time to refine your latest novel? Sorry, my guy. But we need you to dance like a monkey on TikTok, answer every comment notification instead of spending time with your kids, and come up with something witty to say on Bluesky at least twelve times a day.

Yeah, we know social media is cigarettes for the brain. But if you want this thing to sell…

So do we write for the story? Or do we write for the algo, which is your best chance of getting that story seen?

Perhaps I’m too old, too resigned to obscurity, too averse to the Necronomicon of social media, but the theme that has always guided my own writing journey is ‘Craft is Everything’.

Theme is the most precious thing in your story because it comes directly from you. It’s your truth, your outrage, your obsession, your lived experience. It’s the reason academics obsess over theme; because it’s the gateway into the writer’s soul. It’s your contribution to our collective understanding of the universe. It’s your take on the eternal question ‘why?’

Learning how best to communicate that unique answer is a chaotic, exhausting, embarrassing process, but it’s how your story gets told.

If you’ve lost someone, if you’ve loved someone, if you’re enraged at a world that wants to punish you for your very existence, craft is how you get that story out of you.

Catharsis cannot be outsourced. Writing is the point of writing.

But craft is also graft. It’s arse-on-the-chair, put-in-a-shift work, not the kind of arty-farty bollocks people like me spout on Substack in the hope of getting quoted.

“Writing and literature classes can be annoyingly preoccupied by (and pretentious about) theme, approaching it as the most sacred of sacred cows, but (don’t be shocked) it’s really no big deal. If you write a novel, spend weeks and then months catching it word by word, you owe it both to the book and to yourself to lean back (or take a long walk) when you’ve finished and ask yourself why you bothered – why you spent all that time, why it seemed so important. […] It seems to me that every book – at least every one worth reading – is about something. Your job during or just after the first draft is to decide what something or somethings yours is about. Your job in the second draft – one of them, anyway – is to make that something even more clear. This may necessitate some big changes and revisions. The benefits to you and your reader will be clearer focus and a more unified story. It hardly ever fails.”

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft (2000)

Here’s how I believe theme works within the ecosystem of any given story.

A story will land somewhere on a spectrum between ‘THEME’ at one end and ‘MOMENTUM’ at the other. A story that leans more towards ‘THEME’ will be slower, more meditative, but in doing so will gain greater depth and thematic richness.

A story that leans more towards ‘MOMENTUM’ will move faster, be more exciting but will sacrifice a degree of complexity. It’s the difference between the novel and melodrama, between On Chesil Beach and Mad Max: Fury Road.

Some stories lean so far into ‘MOMENTUM’ overdrive that their themes atomise into broad, pervasive values, the stuff the story cares about most of all.

And that’s okay. It’s how melodrama works.

Most stories occupy a middle-ground between the two poles, but knowing the expectations of your readership is crucial. Readers expecting a complex graphic memoir about gender apartheid and the treachery of memory might be disappointed if you deliver 100 pages about a barbarian in a bikini trying to punch a hydra. On the other hand, don’t go Barton Fink and get so fascinated with your theme that you forget why your audience turned up.

“The more fascinated Alien films grew with the richness of their own thematic texture, the more they neglected their humble duty to terrify, and by the time of Alien Resurrection, the series had unspooled into mere marginalia, of archival interest to those who wished to know what happens when you give an Alien movie to a Frenchman to direct.”

Tom Shone, Blockbuster: How the Jaws and Jedi Generation Turned Hollywood Into a Boom-Town (2004)

Theme can speak loud or quiet. It can be complex allegory or just underlying values. But it’s always there, down to your choice of characters and the words you make them speak.

So speak your mind, whether you’re writing One Hundred Years of Solitude or Too Fast, Too Furious but with werewolves. Just remember the cardinal rule of theme laid down by legendary Batman writer Denny O’Neil3: “You can say anything you want, but first you must tell a story.”

Stay weird

YOUR NEXT READ

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

The Clues to a Great Story, TED Talk, Andrew Stanton

Two electrifying auteurs if you count Avi Aster (Hereditary, 2018; Midsommar, 2019). Four if you count Danny and Michael Philippou (Talk to Me, 2022; Bring Her Back, 2025).

Passed down to veteran comic writer John Ostrander who wrote a profound article on theme in issue 12 of the (sadly no longer published) comic-writing magazine Write Now!.

Wise words! What I knew (mainly) but very well put.

I'm trying to rein in the obvious theme in the book I'm writing but I know during the draft stage it's going to end up being bloody obvious and not worry too much about it at this stage. That's for revision.

I've always applied the show don't tell rule to theme: Don't talk about how the invading aliens represent colonialism, just have the aliens take over the world. The rest will speak for itself. Great article!