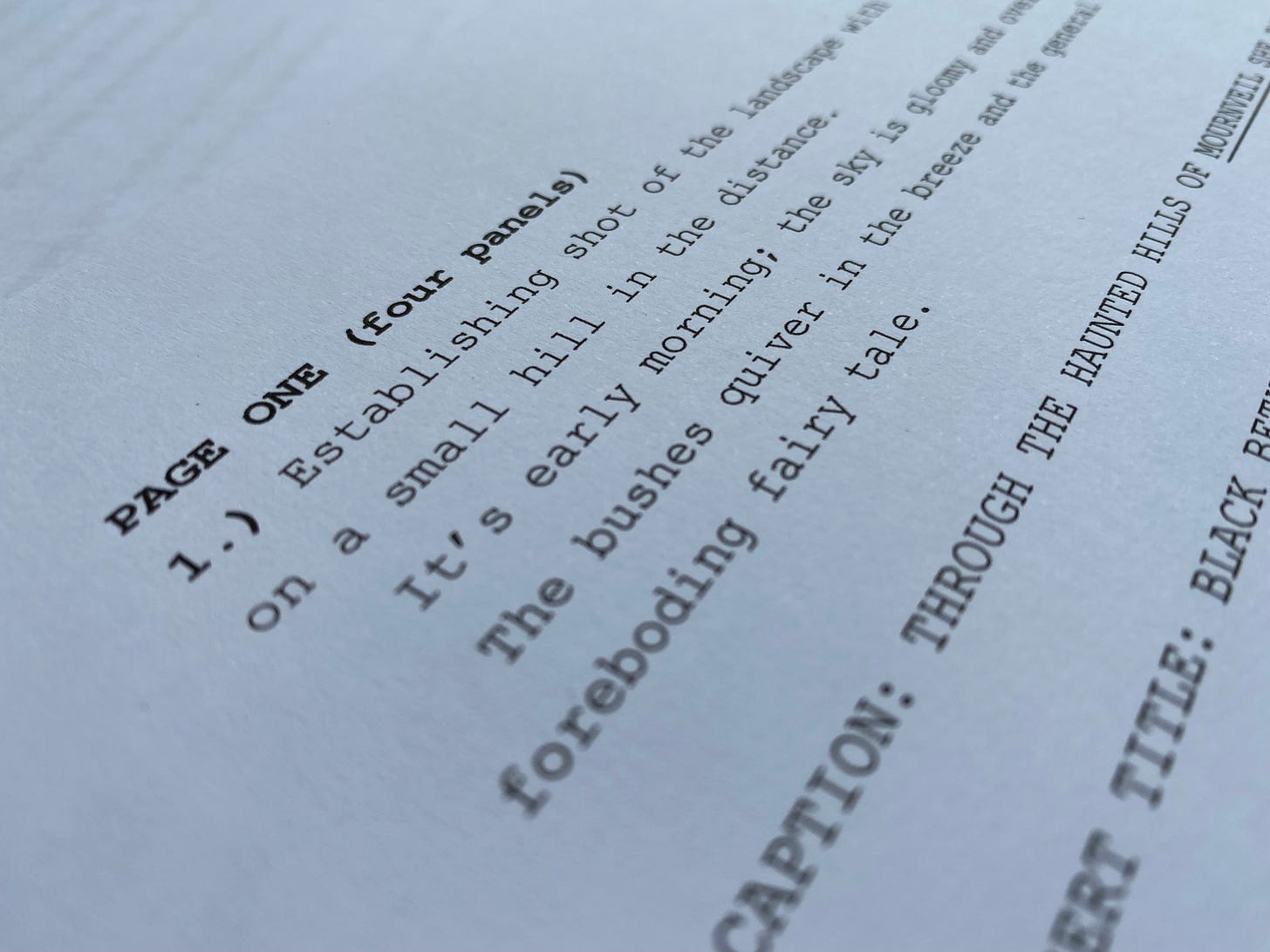

How I Format a Comic-Book Script

The 'correct' way to lay out a script for your comic book depends on what you're writing and who you're writing for. Find out what you need to bear in mind for the sake of you and your creative team.

This piece on how I format a comic script (and – most importantly – why I format it the way I do) was one of the most popular posts on my old blog (over on my portfolio alecworley.com). But since writing it back in 2013, my comics scripting has evolved quite a bit. So it seemed only right that I update it.

For referen…