M.R. James and the Craft of Fear

Learn the subtleties of writing terror from a master of the scary ghost story

The ghost stories of Etonian scholar Montague Rhodes James (1862-1936) are about as perfect in terms of structure and technique as it’s possible to get. With the thirty-three terror tales James penned for his own amusement, including classics such as Casting the Runes and Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad, he revolutionised the form. Building on innovations made by Irish writer J. Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873), James brought horror fiction out of the gothic dungeon and let it loose in the Edwardian drawing room.1

In my estimation, the ghost story occupies a specific place on the spectrum of horror storytelling.2 Unlike the gorgeous gorefests of a Clive Barker or a Poppy Z. Brite, writers of grand guignol spectacle whose gothic ideas are wrought in a Jackson Pollock of flesh and blood, the ghost story gets you when you’re not looking.

Occupying the opposite end of the horror-o-meter where gore and monsters are rarely on show, the ghost story is an altogether subtler mode and demands a certain mastery. The writer must know how to creep up on readers using whispers and tact, techniques of which M.R. James is one of the greatest teachers there is.

A horror connoisseur (i.e. nerd), James read and studied widely. He was particularly admiring of Dickens’ The Signalman (1866), Le Fanu’s The Watcher (1847, revised as The Familiar in 1872) and Margaret Oliphant’s The Open Door (1881).3

As exacting of his own techniques as he was of the genre itself, James outlined his approach to writing in a 1929 essay Some Remarks on Ghost Stories, first published in the Christmas edition of The Bookman.

In the early days of my own self-education in writing, I was as hungry to decipher ‘the rules’ as any other rookie4. So I pounced on James’s essay the moment I found it and several passages have certainly stuck with me over the years when writing my own horror stories…

“The setting and the personages are those of the writer’s own day; they have nothing antique about them…”

“Reticence may be an elderly doctrine to preach, yet from the artistic point of view I am sure it is a sound one. Reticence conduces to effect, blatancy ruins it…”

“The greatest successes have been scored by the authors who can make us envisage a definite time and place, and give us plenty of clear-cut and matter-of-fact detail, but who, when the climax is reached, allow us to be just a little in the dark as to the working of their machinery.”

James’s emphasis on a realistic contemporary setting was echoed in the kitchen-sink realism of horror bestsellers for the rest of the twentieth century, from Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959) to William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist (1971) and just about everything by Stephen King. Once again, this is post-gothic horror, which does away with the notion that terrors only befall those who inhabit bygone fairy tales. These stories reveal that monsters walk among us. They also take the subway and go shopping at Walmart.

As we’re reminded by the shrewd inhabitants of

, the real world is gothic enough if you know where – and how – to look.But James’s insistence on realism isn’t so much philosophical as practical. Readers of horror must be taken by surprise. They expect to see spooky things in a crumbling castle, a neglected graveyard, an abandoned factory. But in a coffee shop? A council estate carpark? Their sock drawer?

“In the infancy of the art we needed the haunted castle on a beetling rock to put us in the right frame: the tendency is not yet extinct, for I have but just read a story with a mysterious mansion on a desolate height in Cornwall and a gentleman practising the worst sort of magic. How often, too, have ruinous old houses been described or shown to me as fit scenes for stories. ‘Can’t you imagine some old monk or friar wandering about this long gallery?’ No, I can’t.”

Ghosts, Treat Them Gently! an essay by M.R. James published in the Evening News, 17th April 1931

If the shock is to land with impact, readers must be prevented from seeing it coming. They must first be put at ease, with a setting full of comfortable and recognisable details. Then, slowly, perhaps without them even realising, the reader’s reality becomes uncertain as they cross a threshold into… somewhere else.

To further demonstrate James’s techniques, here are some examples from his stories…

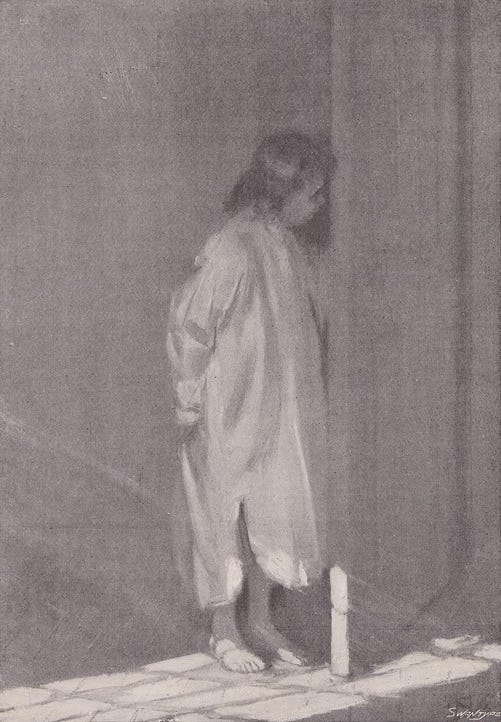

The first is a scene from Lost Hearts, first published in 1895 in The Pall Mall Magazine. It wasn’t one James’s favourites, apparently, but remains a masterclass in economical storytelling at (roughly) 4,000-words.

The story is set in 1811 when an orphan lad by the name of Stephen Elliot is sent to live with a distant, older cousin, Mr Abney, in his remote Lincolnshire home of Aswarby Hall, “a tall, square, red-brick house, built in the reign of Anne; a stone-pillared porch had been added in the purer classical style of 1790; the windows of the house were many, tall and narrow, with small panes and thick white woodwork.”

Before we get into the sample scene, it’s important to note when in the story it lands. Ghost stories tend towards formalism and follow an often recognisable structure.

They’ll begin by introducing a main character who is generally unaware they may be under threat from some Terrible Undefined Something. The secondary characters are established as the motives of the Terrible Something become gradually more defined by way of certain ominous clues.

Then – before the climax – we’ll usually have some kind of first contact, whereby the main character has their first encounter with the Terrible Something, perhaps without them even realising how close they came to harm or what it was they saw.

It bears remembering that James, though a toffee-nosed Etonian, wasn’t a ‘literary’ writer. He wrote his ghost stories to entertain and used to read his tales aloud to friends and students on Christmas Eve. The compelling narrative structure of his stories is as obvious as that of any Hollywood screenplay. He didn’t create mood for mood’s sake. It’s there to drive the story.

So far in Lost Hearts, we’ve met young Stephen, the eccentric Mr Abney and his chatty housekeeper Mrs Bunch. We’ve had our ominous clues regarding Mr Abney’s potentially unhealthy obsession with esoterica. Then there’s Mrs Bunch’s story of a couple of children – both orphans, like Stephen – whom the master took in off the street with “as kind as heart could wish.” Only for each child to have mysteriously disappeared.

Now we’re ready for that first contact…

That night he had a curious dream. At the end of the passage at the top of the house, in which his bedroom was situated, there was an old disused bathroom. It was kept locked, but the upper half of the door was glazed, and, since the muslin curtains which used to hang there had long been gone, you could look in and see the lead-lined bath affixed to the wall on the right hand, with its head towards the window.

On the night of which I am speaking, Stephen Elliott found himself, as he thought, looking through the glazed door. The moon was shining through the window, and he was gazing at a figure which lay in the bath.

His description of what he saw reminds me of what I once beheld myself in the famous vaults of St Michan’s Church in Dublin, which possess the horrid property of preserving corpses from decay for centuries. A figure inexpressibly thin and pathetic, of a dusty leaden colour, enveloped in a shroud-like garment, the thin lips crooked into a faint and dreadful smile, the hands pressed tightly over the region of the heart.

As he looked upon it, a distant, almost inaudible moan seemed to issue from its lips, and the arms began to stir. The terror of the sight forced Stephen backwards, and he awoke to the fact that he was indeed standing on the cold boarded floor of the passage in the full light of the moon. With a courage which I do not think can be common among boys of his age, he went to the door of the bathroom to ascertain if the figure of his dream were really there. It was not, and he went back to bed.

Let’s go over that again…

That night he had a curious dream. At the end of the passage at the top of the house, in which his bedroom was situated, there was an old disused bathroom. It was kept locked, but the upper half of the door was glazed, and, since the muslin curtains which used to hang there had long been gone, you could look in and see the lead-lined bath affixed to the wall on the right hand, with its head towards the window.

That first sentence states that we’re witnessing a dream, though the concrete details that follow (the position of the bath and the windows), rather puts that in doubt. James has the reader on an uncertain footing as he ushers us deeper into the scene.

Among the seemingly prosaic details offered here are three crucial bits of foreshadowing: 1.) the room is locked, 2.) it’s empty, and 3.) it’s disused (those muslin curtains having long been taken down). Before the spectre makes its ex nihilo appearance, James must first establish the emptiness of that space. Like a stage magician, the author is showing you there’s nothing up his sleeve. How then might one explain what happens next?

On the night of which I am speaking, Stephen Elliott found himself, as he thought, looking through the glazed door. The moon was shining through the window, and he was gazing at a figure which lay in the bath.

I love the vagueness of ‘found himself’. Stephen hasn’t walked here or arrived for any specific reason, it’s like he’s suddenly materialised, just like the figure in the bath. There’s also no obvious motive for him being here. We assume he’s either dreaming or sleepwalking, or else drawn here by the malevolent presence that lies in the tub. The reader is kept adrift, subtly off-balance in terms of where they are and what they’re doing here.

And let’s not forget the voyeuristic compulsion at work here. We have a boy peering at someone in the bath and us readers (dirty dogs that we are) are just as unlikely to look away.

His description of what he saw reminds me of what I once beheld myself in the famous vaults of St Michan’s Church in Dublin, which possess the horrid property of preserving corpses from decay for centuries.

James makes a classic sidestep here. Instead of immediately giving us a full description of the awful thing lying the bath, he instead offers an analogy: an innocuous day trip to St Michan’s in Dublin. There’s nothing threatening in that. Or is there? Why else would it be mentioned? The reader’s fight-or-flight response is caught in suspense.

And that “horrid property of preserving corpses from decay for centuries” doesn’t blatantly describe the thing in the bath, but rather encourages you to start imagining what such a corpse might look like.

Oh, the joys of inference. How much the pleasure of fiction is a trusting partnership between reader and author, weaving magic in an artful dance. How tough would it be to depict this reticent scene in a patently visual medium like comics or film?

A figure inexpressibly thin and pathetic, of a dusty leaden colour, enveloped in a shroud-like garment, the thin lips crooked into a faint and dreadful smile, the hands pressed tightly over the region of the heart.

Now we’re getting into it. Sort of.

James’s choice of words keeps the inference-dance going. He doesn’t give us a declarative noun like “boy” or “girl”, “child” or “man”. Instead, we get an ambiguous “figure”. Instead of “grey”, we get the more evocative “dusty leaden colour”. What it’s wearing isn’t the traditional shroud, but rather “shroud-like”.

Troubling questions mount. Why is it smiling? What’s it thinking of doing? Why are its hands pressed tightly over the region of the heart? What’s it hiding? And, oh my God… This bathroom hasn’t been used in ages. How long has that thing been lying there, waiting for someone to see it? Did it draw Stephen here from sleep so the boy could witness its awful self? And shit! I almost forgot! The door’s locked! How the hell did it even get in there!?!

An undeniable threat is creeping into view, but nothing’s going for Stephen’s throat just yet. We’re still in suspense. James said reticence “may be an elderly doctrine to preach” but it’s the essence of suspense from Hitchcock to Tarantino.

As he looked upon it, a distant, almost inaudible moan seemed to issue from its lips, and the arms began to stir. The terror of the sight forced Stephen backwards, and he awoke to the fact that he was indeed standing on the cold boarded floor of the passage in the full light of the moon. With a courage which I do not think can be common among boys of his age, he went to the door of the bathroom to ascertain if the figure of his dream were really there. It was not, and he went back to bed.

After all that careful build-up, James arrives at the final, decisive twitch of potential violence, which may be about to come flying in our direction. But he doesn’t want the climax of this scene to overshadow the greater climax to come at the end of the whole story. So the threat here isn’t too explicit, restricted instead to that ambiguous moan and a mere stirring of the arms.

But the uncanny effect of a thing dead abruptly coming to life is enough to goose anyone’s neurons into fighting or flighting. Our suspense is over and that second sentence returns to young Stephen with the bang of an unequivocal “terror”. That noun feels bright and sudden and visceral after all that ghostly vagueness.

The shock of it dispels the horror and we’re back to the (very British) matter-of-factness with which we opened, comforted by the presence of our paternal narrator commending the boy’s uncommon courage.

Stephen himself has written off this mid-story encounter as a dream, but – crucially – we know better. So much in James’s stories thrives on this kind of dramatic irony, which not only helps maintain suspense, but also keeps the characters from breaking the story. If the ghost story protagonist is made aware too early of the reality of their peril, they risk ending the story prematurely by doing what any sensible reader would do and getting the f*** out of there.

Here's another mid-story scene from James’s Rats (first published in 1929 in the March edition of At Random magazine). Another exemplar of economy that’s even shorter than Lost Hearts at roughly 2,500 words.

A Cambridge student known only as Mr Thompson is guesting at a seaside inn, established with typically Jamesian matter-of-factness and precision. “It is a tall red-brick house, narrow for its height; perhaps it was built about 1770.” Thompson learns of the presence of a white stone embedded on a heath overlooking the sea, the sort of stone that might once have supported a gallows… His curiosity peaked, Mr Thompson sets about exploring the inn itself one sunny afternoon.

Nobody at all, it seemed, was indoors; probably, as it was market day, they were all gone to the town, except perhaps a maid in the bar. Very still the house was, and the sun shone really hot; early flies buzzed in the window-panes. So he explored.

The room facing his own was undistinguished except for an old print of Bury St. Edmunds; the two next him on his side of the passage were gay and clean, with one window apiece, whereas his had two. Remained the south-west room, opposite to the last which he had entered. This was locked; but Thomson was in a mood of quite indefensible curiosity, and feeling confident that there could be no damaging secrets in a place so easily got at, he proceeded to fetch the key of his own room, and when that did not answer, to collect the keys of the other three. One of them fitted, and he opened the door.

The room had two windows looking south and west, so it was as bright and the sun as hot upon it as could be. Here there was no carpet, but bare boards; no pictures, no washing-stand, only a bed, in the farther corner: an iron bed, with mattress and bolster, covered with a bluish check counterpane. As featureless a room as you can well imagine, and yet there was something that made Thomson close the door very quickly and yet quietly behind him and lean against the window-sill in the passage, actually quivering all over.

It was this, that under the counterpane someone lay, and not only lay, but stirred. That it was some one and not some thing was certain, because the shape of a head was unmistakable on the bolster; and yet it was all covered, and no one lies with covered head but a dead person; and this was not dead, not truly dead, for it heaved and shivered.

If he had seen these things in dusk or by the light of a flickering candle, Thomson could have comforted himself and talked of fancy. On this bright day that was impossible. What was to be done?

First, lock the door at all costs. Very gingerly he approached it and bending down listened, holding his breath; perhaps there might be a sound of heavy breathing, and a prosaic explanation. There was absolute silence. But as, with a rather tremulous hand, he put the key into its hole and turned it, it rattled, and on the instant a stumbling padding tread was heard coming towards the door.

Taking a closer look…

Nobody at all, it seemed, was indoors; probably, as it was market day, they were all gone to the town, except perhaps a maid in the bar. Very still the house was, and the sun shone really hot; early flies buzzed in the window-panes. So he explored.

Once again, emptiness. Nothing up my sleeve. But unlike the empty bathroom in Lost Hearts, the emptiness here is less enclosed, more expansive, more inviting of exploration. This gives Mr Thomson a clear line of action that will carry him through this scene: to explore and find clues pertaining to that mysterious stone. The image of the buzzing flies adds a subtle bit of deathly foreboding.

The room facing his own was undistinguished except for an old print of Bury St. Edmunds; the two next him on his side of the passage were gay and clean, with one window apiece, whereas his had two. Remained the south-west room, opposite to the last which he had entered. This was locked; but Thomson was in a mood of quite indefensible curiosity, and feeling confident that there could be no damaging secrets in a place so easily got at, he proceeded to fetch the key of his own room, and when that did not answer, to collect the keys of the other three. One of them fitted, and he opened the door.

Again with the matter-of-fact details. Thompson is literally counting the number of windows and noting the direction of each room, his pedantic inventory enlivened by that vivid detail of the old print of Bury St. Edmonds.

The geography of the scene is mapped out precisely. Unlike the young somnambulist of Lost Hearts, Mr Thompson is on rock-solid ground here. Yet the emptiness of the first paragraph has opened onto yet more enticing emptiness, like the subterranean mall in Kane Pixels’ astonishing horror short The Rolling Giant.

He hasn’t yet met his objective, so the scene must continue.

Then – in a hall full of open doors – he finds one that’s been purposefully locked. See how James shows rather than tells us how feverish Thompson’s curiosity has become now, giving us the action of him fetching all those keys and trying each one.

The room had two windows looking south and west, so it was as bright and the sun as hot upon it as could be. Here there was no carpet, but bare boards; no pictures, no washing-stand, only a bed, in the farther corner: an iron bed, with mattress and bolster, covered with a bluish check counterpane. As featureless a room as you can well imagine, and yet there was something that made Thomson close the door very quickly and yet quietly behind him and lean against the window-sill in the passage, actually quivering all over.

Upon opening the door, Thompson’s survey continues, and it’s exhaustive but for one crucial detail, which James doesn’t yet describe at all. Instead, he leaves us with an uncanny space that’s empty yet somehow occupied. I love how Thompson closes the door “quickly and yet quietly”, suggesting a fearful sense of not wishing to disturb whatever it is he’s just seen. And nowhere does James’s description tell us Thompson is scared, but instead shows him “quivering all over.”

It was this, that under the counterpane someone lay, and not only lay, but stirred. That it was some one and not some thing was certain, because the shape of a head was unmistakable on the bolster; and yet it was all covered, and no one lies with covered head but a dead person; and this was not dead, not truly dead, for it heaved and shivered.

James rides the ambiguity line throughout here, withholding anything definite. It’s a person, but why is it covered. It’s dead, but then why is it moving? From the concrete descriptions of the rest of the inn, we’re suddenly thrown into a terrifying liminal space. Had James described the rest of the inn in gothic, consciously ‘spooky’ terms, there would be no shocking contrast once the door was opened.

If he had seen these things in dusk or by the light of a flickering candle, Thomson could have comforted himself and talked of fancy. On this bright day that was impossible. What was to be done?

What indeed? Unlike the moonlit apparition of Lost Hearts, this spectre has materialised in broad daylight. This isn’t when ghosts are supposed to appear! What in God’s name is the world – or for that matter, reality – coming to? Thompson’s shock feels existential.

First, lock the door at all costs. Very gingerly he approached it and bending down listened, holding his breath; perhaps there might be a sound of heavy breathing, and a prosaic explanation. There was absolute silence. But as, with a rather tremulous hand, he put the key into its hole and turned it, it rattled, and on the instant a stumbling padding tread was heard coming towards the door.

And we’re back to reality with that short, decisive opening sentence. Thompson remains shook, clinging to his sanity. He knows something’s moving in there, yet that thing isn’t breathing.

This whole scene isn’t teaching us how to maintain suspense, but rather how to maintain those contrasts necessary to create ambiguity, that uncanny space between the real and the explicitly unreal. In a monster movie, say, Godzilla is accepted as real, as real as doorknobs and aeroplanes. But James can’t afford to employ anything so solid and unequivocal when conjuring his ghosts.

Another shocking contrast, from silence to something rushing at the door. Should James have cut those adjectives “stumbling, padding”? Absolutely not. Because they’re not only colouring the otherwise plain noun “tread”, but also inferring that whatever horror lurks behind that door has trouble walking on bare, still-fleshy feet.

Do we find out what were the apparitions of Lost Hearts and Rats? Yes, but James makes his readers work for it. Rather than explain his horrors as plainly as if he were reading off Wikipedia, he gives you only hints (“thin lips crooked into a faint and dreadful smile”, “a stumbling, padding tread”), prompting you to come up with something all the more vivid and eerie because you thought of it for yourself.

But do we know how such things are allowed to roam the Earth in James’s stories? Are we given an overall sense of how the physics of the uncanny work in this realm? Can some enterprising movie executive have enough to one day conceive an M.R. ‘Universe’? Thankfully not, because, as James quite rightly said, “We do not want to see the bones of [the author’s] theory about the supernatural.”

Like all great horror authors, James knew where to stop.

Stay weird.

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

Landmark movies Night of the Living Dead and Rosemary’s Baby (both 1968) did the same for horror cinema. Now the monsters no longer dwelled in faraway Castle Dracula. They wandered blue-collar Pittsburgh or else conspired behind the walls of a comfortable New York brownstone. The monsters were no longer out there, waiting to come in - they were already here. Worse still, those monsters were us!

I went into this further in my piece How to Write a Truly Scary Horror Comic.

In a private letter to Nicholas Llewelyn Davies (one of the five Llewelyn brothers who were the troubled inspiration for Peter Pan by their foster-father J.M. Barrie), James revealed he was most definitely not a fan of H.P. Lovecraft (“whose style is of the most offensive. He uses the word cosmic about 24 times”), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (“which fails to impress me as it should”), or Matthew Lewis’s Georgian shocker The Monk (“really not fit to be read”).

Pro tip: Don’t obsess over rules. There are no rules, only fluid principles. Concern yourself instead with the brute mechanics of technique. Keep practising until technique becomes instinct, then apply both instinct and judgement to communicate your vision as best you can. To quote Po from Kung Fu Panda, “There is no secret ingredient. It’s just you.”

The most perfect ghost stories ever written!

In this sub-genre of horror, James is the author all the others want to be like...