“What’s up, guys! Wyatt here.”

The horror begins with the cheerful banality of countless YouTube videos, as our teenage host treks through secluded woodland, chuckling as he passes an ‘Area Closed’ sign, until he finds the really cool thing he’s hoping will finally get his subscribers into the high hundreds.

Hidden in the shade of an old tree, we find what looks like some kind of burrow. Curious, we peer inside and see a flight of concrete stairs, eerily symmetrical, perfectly lit, leading down, down, down into seeming infinity.

Thus opens The Rolling Giant, easily one of the most effective horror movies of 2023 and – somehow – the least talked about.

It’s a stunning 50-minute YouTube short and the latest in a so-far three-part series subtitled The Oldest View (comprising not-strictly-necessary prologue shorts Renewal and Beneath the Earth), written and directed by 18-year old wunderkind Kane Pixels (real name Kane Parsons). He’s a VFX artist, musician and filmmaker who has been creating seminal horror shorts for the last few years in between homework assignments and thinking about college applications.

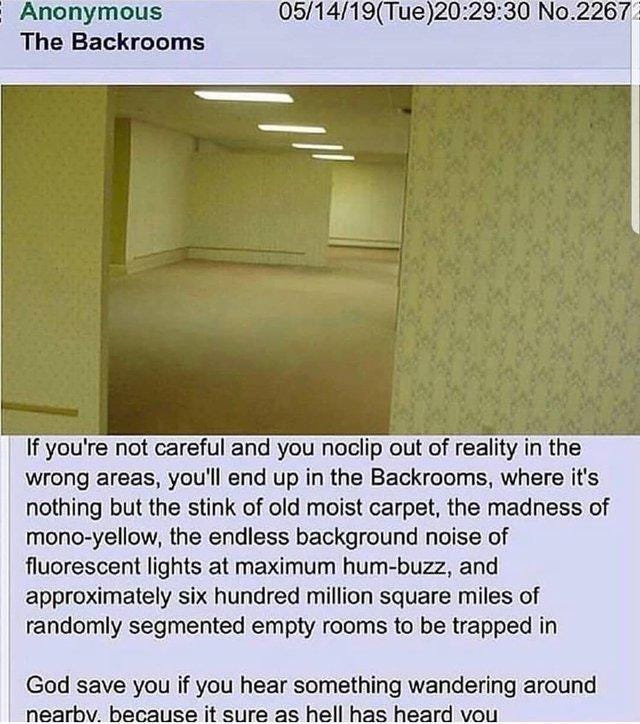

His previous nine-minute short, The Backrooms (2022), was inspired by an anonymous 4chan thread about unsettling environments. This deeply uncanny found-footage horror piece features a hapless high-school filmmaker who ‘no-clips’1 out of reality only to find himself trapped in a formaldehyde-yellow maze of office spaces, stalked by a screeching, lumbering… something.

According to a 2023 interview with fellow YouTuber Desolar, The Backrooms took Kane’s YouTube subs from barely 200,000 to over one million in a little over six weeks and quickly expanded into a web-series that both teased and accommodated the inevitable viewer theories that followed - all of them straining to defuse the very inexplicability that makes the horror of The Backrooms so effective.

The Backrooms also inspired a host of chased-through-a-maze creations by indie and DIY game designers (there remains some debate over whether or not The Backrooms is essentially an open-source concept), as well as boosted wider artistic interest in ‘liminal spaces’. In February 2023, Deadline announced that Kane was working with A24 to direct a (copyrightable) Backrooms feature film from a script by Robert Patino.

The Rolling Giant continues the technical assurance and minimalist brilliance of The Backrooms and is arguably Kane’s most accomplished movie yet, assuring us that his previous hit was not just a viral fluke.

Now settle down, turn off the lights and watch.

And don’t read on if you don’t want spoilers!

Beyond Kane’s seemingly instinctive grasp of suspense techniques, his mature patience for building atmosphere, his rare understanding that sustaining the uncanny demands a tightrope walk between logic and mystery, the most startling thing about this movie is that none of it is real.

Like The Backrooms, The Rolling Giant is an analogue horror movie made almost entirely with CGI. That mall ‘set’ is based on what used to be a real building: a beige anonymity called the Valley View Mall, which once stood on Interstate 635 and Preston Road in Dallas, Texas.2

The 3D artist, sound designer and Rolling Giant collaborator known online as Corrupt painstakingly mapped and recreated the Valley View Mall using open-source graphics software Blender. Working from an exhaustive archive of maps and photos, Corrupt recreated every food court and storefront, resurrecting every inch of that lost environment down to the last floor tile.

To the casual viewer, the mall of The Rolling Giant is terrifyingly indistinguishable from the real thing, so much so one might be forgiven for suspecting some kind of PR shenanigans on the part of the filmmakers. Are you sure you guys didn’t just sneak into a deserted mall with a camera?

“Corrupt would build out the geometry of a specific section of the mall, starting with the food court and the fountains, and I would go in and texture everything. A lot of the textures are custom, modified from different texture libraries out there somewhere, just photos taken. But I’d go in, do that, do all the textures and then do a pass of props, plants, detailing. Like the fountain plants, for example. [I’d] go in, fill all the pots with dirt, then plants, then texture all that. And so really, by the time I was done with that, Corrupt had done [another] little modular section of the mall I could glue in.”

Kane Pixels, 2023 interview with Desolar

Even our protagonist doesn’t exist!

Wyatt’s held-held camera is yet another virtual conceit, rendered to mimic the jostle of human movement with Wyatt’s squeaking footsteps added in post.

“It’s a combination of hand keyframes and tracked camera motion recorded by a brilliant VFX artist Ian Hubert… And this one plug-in I’ve used for couple of years now… [but] the plug-in isn’t just carrying all the weight there, you really need to do a lot to make it look right, especially when you’re walking, doing all sorts of dynamic movements. But without that it would look very stilted, robotic. It’s sort of like a pass to put over the whole thing, like adding imperfections to it all.”

Kane Pixels, 2023 interview with Desolar

That ghastly bearded Giant was yet another virtual recreation. Like the 4chan image that inspired The Backrooms, Kane chanced upon a reference pic of the giant on his hard drive, culled from somewhere on the internet. Reverse image searches revealed it resided in the Valley View Mall, a parade float piece created by Dallas sculptor and artist Kevin Obregon in celebration of local 19th century botanist Julien Reverchon.

His parade over, the Giant saw out his days decorating the mall and providing selfies for shoppers.3 And when the lights went out and the mall was dark and empty, he was still there, his sorcerer’s beard, his midnight robes, his blossoming paws raised in entreaty or perhaps alarm, a totem of some ancient meaning now left standing outside Sears and JCPenney, no-clipped from his original context.

“Years ago, Lon Chaney said: ‘A clown is funny in the circus ring, but what would be the normal reaction to opening a door at midnight and finding the same clown standing there in the moonlight?’”

Robert Bloch, Famous Monsters of Filmland, May, 1962

The Giant isn’t some franchise vaudevillian like Freddy Kruger or Ghostface, made comfortable and familiar through merch and advertising. It’s a handmade artefact, unique and therefore suspicious. This isn’t a branded item. It’s not selling anything. So what could possibly have prompted its making? What was its creator even thinking? What could it be thinking?

“Among all the psychical uncertainties that can become a cause for the uncanny feeling to arise, there is one in particular that is able to develop a fairly regular, powerful and very general effect: namely, doubt as to whether an apparently living being really is animate and, conversely, doubt as to whether a lifeless object may not in fact be animate.”

Ernst Jentsch, On the Psychology of the Uncanny, 1906

With its cast of virtual doppelgangers and its exploration of the limbo states between real and unreal, the familiar and the strange, the inanimate yet full of living malevolence, The Rolling Giant is uncanny to the core. And yet it’s the convincingly skittish performance of our virtual central character that makes the movie so compelling.

What could be more spontaneously human than the moment when Wyatt lifts that metal shutter only to panic like a frightened little kid when it lets out a deafening squeal. Before he’s even entered that subterranean mall, our protagonist is established as scared and therefore vulnerable.

His trepidation is palpable as he hesitates before every corner, his voice awed and breathless, flashlight blazing, announcing his presence to whatever lurks in the dark. Most human of all is that disbelieving burble of terror we hear when he steps back out onto the concourse and finds the entire mall has been reduced to primordial swamp, its muzak replaced by what sounds like a religious service celebrating whatever Lovecraftian apocalypse has transpired here.

We feel the inexorable pull of Wyatt’s curiosity too, the downfall of countless B-horror protagonists tragically curious to find out what was that noise they just heard out by the woodchipper. “No way I’m walking away from this thing,” says Wyatt. “I need answers.” He’s as hungry for resolution as the fan theorists who obsess over The Backrooms.

Horror movies are known for taking delight in making us complicit in their atrocities – like the entertaining fatalities of the Friday the 13th movies or the prowling subjective camerawork of a Halloween or a Terminator, allowing us a share of the hunter’s power - though few movies dare to call their viewers to account for such sadism.

Wyatt chuckles in disbelief as he prepares to venture down those concrete stairs, like he’s stumbled upon buried treasure, YouTube gold. But would he have ventured into such an obviously hazardous situation if he didn’t have a camera to record his discoveries? Or a subscriber-base awaiting distraction? How often do we endorse inadvisable behaviour online simply by viewing it? If a YouTuber were to suffer a cholesterol-induced stroke from years of competitive eating, or asbestos poisoning from urban exploring, or a mental breakdown from trying to satisfy the demands of the algorithm, how many of our views, likes, shares and subscribes will have helped encourage their collapse?

When Wyatt flees only to find the stairs have inexplicably caved in, trapping him forever in this empty consumer maze, his response feels piteously apologetic, like he’s sorry for letting us down. “I really fucked up, guys.”

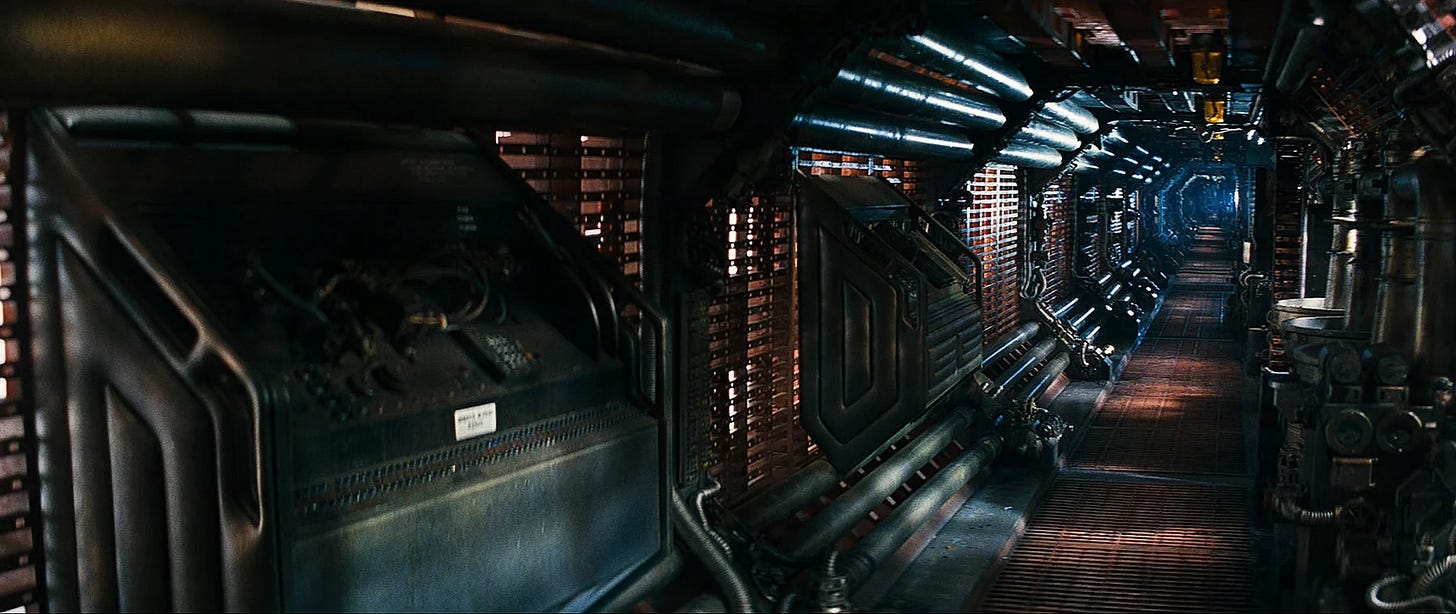

Like George A. Romero’s milestone Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Rolling Giant taps into a rich seam of contemporary anxieties and Kane demonstrates comparable skill in orchestrating his scares. Like Ridley Scott’s Alien or John Carpenter’s Halloween, Kane’s mise en scene4 is always off-kilter, always with one eye on impenetrable shadows lurking in the background, on spaces whose emptiness invites the arrival of something dreadful.

The movie’s rhythm feels believably irregular, at times overlong, unedited. And I love how Kane establishes the rhythm of a startled pan left or right to reveal nothing there but an empty corridor. He does this again and again, until you’re so used to it that when something does appear the shock of it freezes the soul. The Rolling Giant’s sense of unease is so artfully conjured, you might not realise just closely the movie sticks to a generic story structure.

One wonders if the director has a copy of Save the Cat on his bookshelf. We have our ‘ordinary world’ of sunny roadside tracking shots en route to our destination, the jaunty background music as Wyatt rambles about his everyday life of college and comments sections.

The sense of hubris deepens, so typical in a horror story to hint that the protagonist may have brought all this upon themselves. In the prologue short, Beneath the Earth, Wyatt publicly dares the private landowners to ‘sue me’. How arrogant. How punishable his sense of privilege. Wyatt’s isolation deepens too as he descends the stairs, revealing he found out nothing about this place online, before ‘Breaking into Two’ as he enters the empty mall. His escape route crumbles bang on the Midpoint. The ‘Bad Guys Close In’ as thunder inexplicably rumbles underground, lights flicker, the horror mounts, nothing adds up and ‘All Is Lost’.

I have my own theory on horror structure5 and believe it doesn’t really fit the classic narrative template that ascends towards healing or resolution. I feel like the downward trajectory of tragedy is a far more natural fit, which is exactly how things wrap up here. Wyatt’s objective (to get the hell out of here!) is thwarted at every turn. He’s given a teasing glimmer of hope when he finds those maps in the manager’s office and triangulates a possible escape route. But instead of being rewarded for his courage and ingenuity – as might happen in the traditional ascendent healing narrative – his salvation is snatched away without mercy.

For all its liminal strangeness, The Rolling Giant is underpinned by perfectly familiar beats. It progresses logically, its story adds up and never quite feels random or undramatic. Unlike Kyle Edward Ball’s stunning avant garde horror Skinamarink (2022), The Rolling Giant’s weirdness and obscurity doesn’t feel confrontational, rather it feels teasing, comfortably entertaining.

“I feel a lot of [webseries] fall into the territory of being too cryptic to fully enjoy watching in a comfortable way and while my series definitely is cryptic, it’s just coherent enough for people to sit down and have a mysterious but logical viewing experience.”

Kane Pixels, 2023 interview with Desolar

It turns out Kane isn’t much of a horror movie fan, which might explain why The Rolling Giant and The Backrooms feel so much like their own thing, oblivious to recognisable tropes and tedious fanservice. Unlike, say, Wes Craven’s Scream (1996) or Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017), they’re not in conversation with their own genre. Inspired by memes, reddit, 4chan and DIY gaming, rendered in open-source software by a community of hobbyists, Kane’s movies are rooted in not in movie culture, but online culture.

This vaporous virtual world is itself a liminal space, divorced from the realm of the physical and the living, and in which you can no-clip from one universe to another with the click of a mouse. Reality here is treacherous. Nothing you see is to be believed and therefore truth is whatever we make of it.

As with any form of storytelling it’s the absence of certainty that invites the imagination, allowing both artist and reader/viewer to create a world in tandem. The Rolling Giant raises enticing questions every step of the way. What are those stairs doing here? What’s at the bottom? Why’s there a mall down here? Where did everybody go? Who’s turning on those lights? What the hell was that noise?

And it’s that quest for certainty that draws us to our doom.

Stay weird.

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

‘No-clipping’ is a gaming term that derives from a cheat code for 1992’s Wolfenstein 3D. The code allowed players to move through the game environment with collisions disabled, allowing them to pass through walls, solid objects, etc.

Opening in 1973, the mall declined throughout the 2000s - though it hosted a thriving local art scene - before its eventual demolition completed in May 2023.

Sadly, the original Giant got bulldozed, along with the rest of the mall.

Boy, I haven’t used that phrase since I wrote for Sight & Sound.

Which I’ll go into with a future essay,

Thanks for bringing this to our attention! Your deconstruction is spot-on. What an unsettling 50 minutes.

LOVE KP! Have been following him on YouTube for what seems like years. Sometimes hard to remember he's just a kid.