This four-part essay is an updated and extended version of a piece first published on my blog back in 2014, itself prompted by a popular talk I gave at Bristol Comic Expo the same year.

I submitted my first script to 2000 AD knocking on twenty years ago. Back then the legendary British sci-fi anthology was your most viable option if you were unfortunate enough to be living in Britain and deluded enough to want to work in newsstand comics. The venerable war title Commando took open submissions, but everyone else - Titan, Panini and The Beano - were a brick wall.1 To get in with these publishers you needed to have gotten in somewhere else first. Similarly, the notion of writing for Marvel or DC was something akin to the whimsy of a crack-addled Leprechaun.

Today, if you’re British and want to ‘break in’ to comics, there are several other doors to publication that await your crowbar. Crowdfunding is now an option if you’ve got the time, the know-how and the followers2. And if you’re funding a project with nothing but passion, potential collaborators can be easily reached via social media. You can host projects online on the platform of your choice, forming the basis of a big shiny portfolio over which potential editors can then feign interest.

Taking these routes to assembling a complete comics project can take months, maybe years, in between day jobs and other commitments. On the other hand, writing a single four-page script can take only a week or two of solid focus3. Almost two decades on from my first sale to 2000 AD, I can safely say that if I were starting out now then I’d still be making cold submissions wherever I could.

The lessons I learned going through that submissions process have not only served me well within the field of comics, but also applied every time I’ve fought to broaden my professional horizons by cracking a new market. The tactics and mindset I adopted in writing those first Future Shocks for 2000 AD come into play whenever I’m making a cold submission.

Whether you’re submitting a short story to Tor.com or the submissions window at Warhammer’s Black Library, sending a screenplay or novel to a prospective agent, or pitching an audio drama to a producer, the ordeal is the same. The hard work gets done and it gets done for free. You toil not only with no promise of success, but also with the seeming certainty of failure. You do your due diligence, your market research, and get the project in the best shape it can possibly be before taking aim at the submission window you stand the best chance of breaking. Line up those crosshairs, fire, then walk away.

This Zen state of acting without expecting reward is crucial for your long-term mental survival. It’s also your best chance of success. But don’t ever tell yourself that; self-consciousness invites failure.

Another thing Tharg’s Future Shocks taught me was to beware the ‘big break’ delusion, a lie promised by too many writing competitions, comics writing courses and the general culture of comic-book stardom. Writing will forever be a battle, same as when you started out, no matter how easy those who’ve ‘made it’ make it look.

READ: Why Writers Are Full of S*** (And Why We Have To Be) Image is key to success for writers today. But is the drive to fictionalise ourselves a good thing or a toxic necessity? What does it say to incoming talent?

There is no ‘made it’.

Neil Gaiman is a noob. That kid fresh out of college is a genius. It’s all relative. Obstacles persist and will forever find new and horrible ways to obscure your target and stab holes in your hard-won confidence.

But if you can learn how to deal with that shit now, you’ll be ready for almost anything a career in writing can throw at you.

So what the heck is a Tharg’s Future Shock?

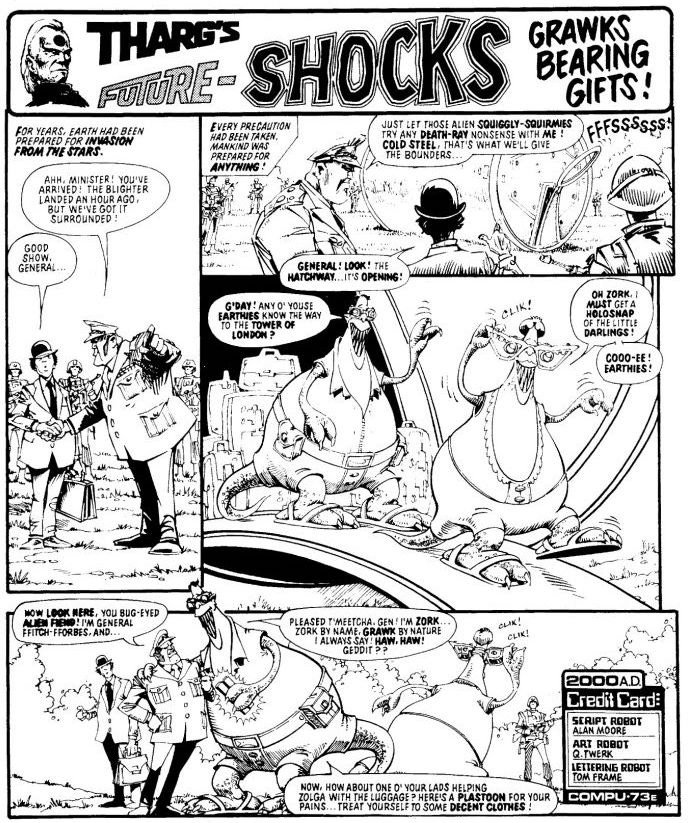

According to the 2000 AD submission guidelines, they’re “self-contained, four-page science-fiction short stories with a twist ending”. Think Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits or Black Mirror. They pop up several times a year in 2000 AD and the very first was published in 2000 AD #25 (1977)4.

It’s how Alan Moore started out. Indeed, tales like his Grawks Bearing Gifts, An American Werewolf in Space and Mister, Could You Use a Squonge? remain benchmarks in the series in terms of inventiveness and humour5.

The series evolved into several genre variants over the years, all employing the same format: Terror Tales (horror), Time Twisters (time travel) and Past Imperfect (alternative histories).

Tharg’s Future Shocks are (or were) the route through which the majority of new (mainly UK) writers come to 2000 AD and out into the wider world of comics.6 I wrote thirteen of them in total before graduating to writing Dredd, Judge Anderson, Robo-Hunter, Durham Red and other stuff, which got me work writing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Star Wars for Panini, which got me fiction and audio work on Warhammer and so on. Work begets work.

As with pretty much every open submissions policy I’ve seen in recent years, 2000 AD has had to impose limited submission windows instead of leaving their door open all year round. But the comic has countered this by hosting regular Talent Search competitions, if you’re brave enough to pitch a Future Shock in front of an audience at a comic convention7.

Either way, 2000 AD’s (semi) open-door submissions policy means that anyone can take a crack at pitching or writing a Future Shock and have a fair shot at getting it published.

READ: How I Format a Comic-Book Script The 'correct' way to lay out a script for your comic book depends on what you're writing and who you're writing for. Find out what you need to bear in mind for the sake of you and your creative team

Whatever it is that you’re pitching or submitting, I can’t tell you how to get it accepted. I’m not the editor. I’m the freelancer. I’m the one on the outside looking in and as such have no idea what the editor does or doesn’t do, what processes they may or may not go through, what they may favour or can't stand.

All I can tell you is what works for me, based on the lessons I learned when I first started submitting Future Shocks to 2000 AD. Hopefully, this might prove a useful model upon which to compare your own submission tactics.

The truth is, all anyone can tell you is what worked for them. Telling people how to break into comics or screenwriting or anything else is like telling them how to lose their virginity. I can tell you how I lost mine, but I can’t tell you how to lose yours.

Everyone’s circumstances are different. Everyone’s starting point and experience and capacity for learning is at a different level. Different people require different advice.

That said, I can offer a few surefire tactics towards surviving any submissions process and making any writer profoundly rejection-proof…

Until then, stay weird.

READ: My Future Shock Hell! Chapter 2 How to survive the submissions process by rejection-proofing your soul

READ: My Future Shock Hell! Chapter 3 Why on Earth do you want to write comic books?

READ: My Future Shock Hell! Chapter 4 Why your best shot is all that will ever matter

I tried Commando several times and got bounced every time by then-editor George Low who was an absolute gentleman. He answered within days, was friendly and encouraged me to keep submitting. But it took me way too much time to research whatever historical theatre of war I fancied writing about, so 2000 AD it was. But if military history is your thing and you want to work in comics then these guys are definitely a viable option. Here’s their submission guidelines.

Hell, if you’ve got that much of a following, then comics publishers may come looking for you! Founding Executive Editor of Wired Kevin Kelly put forward the seductive ‘One Thousand True Fans’ theory, which posits that if you can gather one-thousand loyal cultists who’ll buy anything with your name on it, they alone will give you enough to live on every month. But if you’re that big then you’re probably too big to be wasting time writing comics for thirty quid a page! The other thing everyone forgets about the Thousand True Fans theory is that that magic number constitutes only a fraction of your total followers. So you’ll need to accrue tens of thousands of mildly engaged or openly indifferent followers before you hit paydirt.

These days I can put out a four-page comic script in under four days (at around five hours a day), from initial idea to final edit. Starting out, I would have been a lot slower.

King of the World by Steve Moore and Joaquin Blázquez, in which an ambitious warlord conquers a rival tribe and declares himself ‘King of the World’, unaware that he’s actually a tiny specimen on an alien ant farm.

These days, Moore is hailed for his ‘serious’ works, perhaps an indication of how current comic-book culture strains for middle-class respectability. Go read his Future Shocks and you’ll see he’s a cosmic comedian on a par with Douglas Adams.

Notable big-name exceptions are Kieron Gillen and Warren Ellis. Also, 2000 AD writers Alex de Campi and Ales Kot swerved a Future Shock apprenticeship, but only having first proved themselves on a dozen other comics elsewhere.

Subscribe to the 2000 AD ‘Thrill-Mail’ newsletter to keep an eye on future Talent Search and submissions news.

The idea of the big break is such a persistent one. I did have big breaks, but I can only see them in retrospect, and they were quite small at the time - a conversation on a bus with an editor that meant they would look at a spec short story. Saying 'yes' to an offer that did not seem that appealing. But they were the pivot moments, the big breaks, and they looked nothing like they 'should'.

Thanks for sharing!