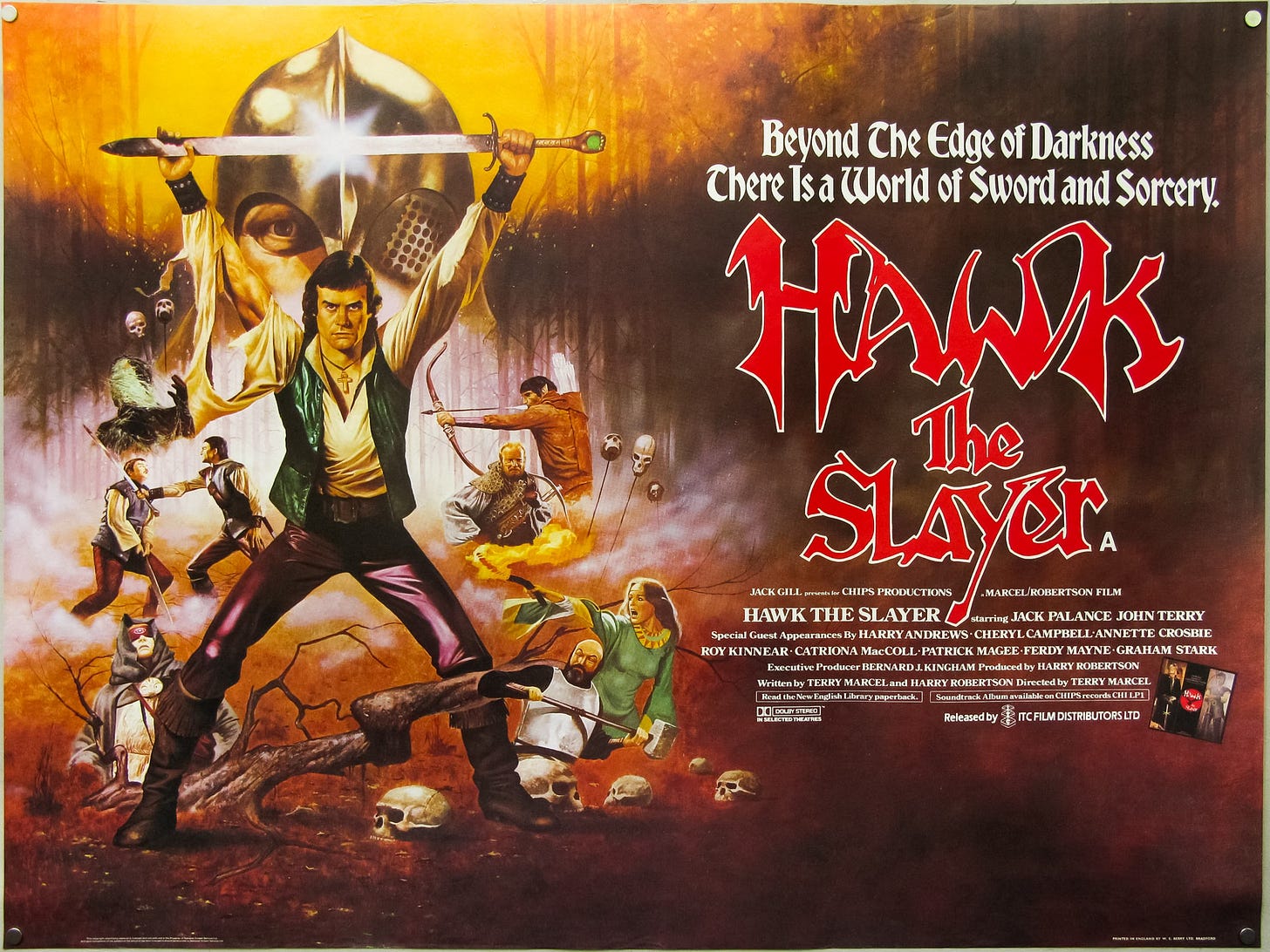

There can surely be no rational defence of Terry Marcel’s ramshackle British sword and sorcery movie Hawk the Slayer (1980). By no sane definition can it be considered great cinema. It falters too often, its ambitions too clearly out of range of its meagre budget. Why then is it so greatly loved? Why are its devotees happy to accept the wayward acting, the threadbare production values, the Silly String special effects, and invest so deeply in its misty medieval world? Social media reveals micro-communities of miniature-makers, role-players, prop hunters1, fan artists and writers. These followers aren’t showing up to look down on a camp extravaganza; they’re here to take part.

It’s the tale of a Cain-and-Abel clash between two brothers: one-eyed bad guy Voltan (Jack Palance, going apeshit in every single scene) versus wandering good guy Hawk (John Terry, hardly acting at all). When Hawk inherits the ancestral Mindsword, Voltan runs amok and kidnaps a nun, forcing Hawk to recruit a rescue team of former comrades: a mallet-hefting giant (Carry On stalwart Bernard Bresslaw), an elf bowman so quick on the draw he’s like a medieval machine-gun emplacement (Ray Charleson), and a whip-cracking, snack-obsessed dwarf (Peter O’Farrell).

Hawk the Slayer has been subjected to many a smug, piss-taking commentary on YouTube, though as an example of ‘So-Bad-It’s-Good’ Hawk is ultimately unrewarding. Even its harshest critics will admit that much love clearly went into its making. The movie has such a boyish enthusiasm for high adventure in an age undreamed of that laughing at it can’t help but feel mean-spirited. VHS-era sleaze like Teodoro Ricci’s Thor the Conqueror (1982) and John Watson’s Deathstalker (1983) are far more deserving of vicious mockery.2

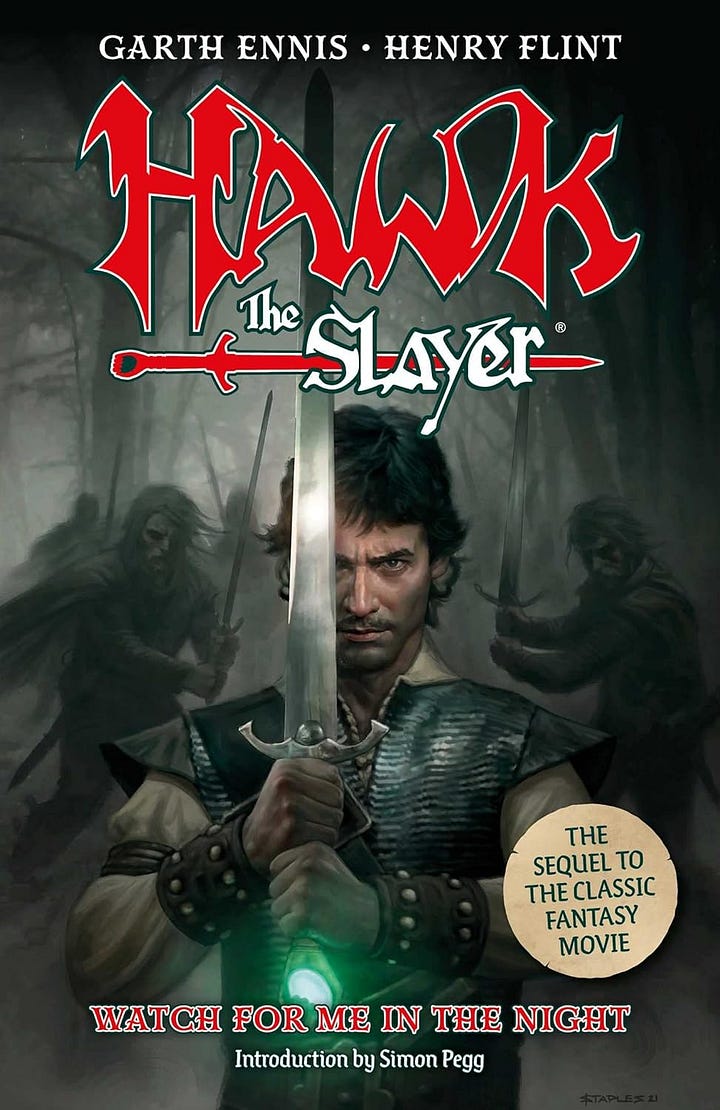

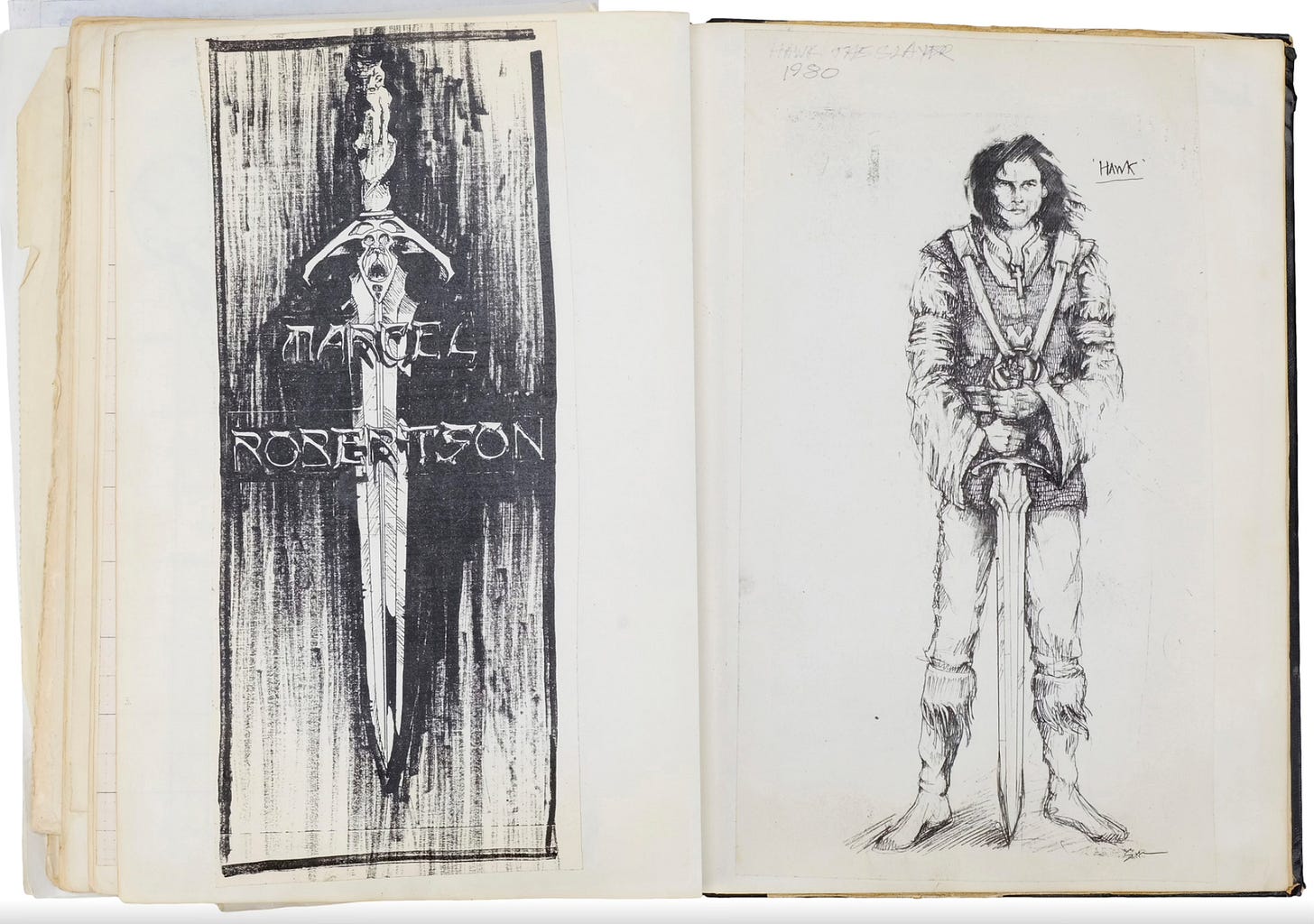

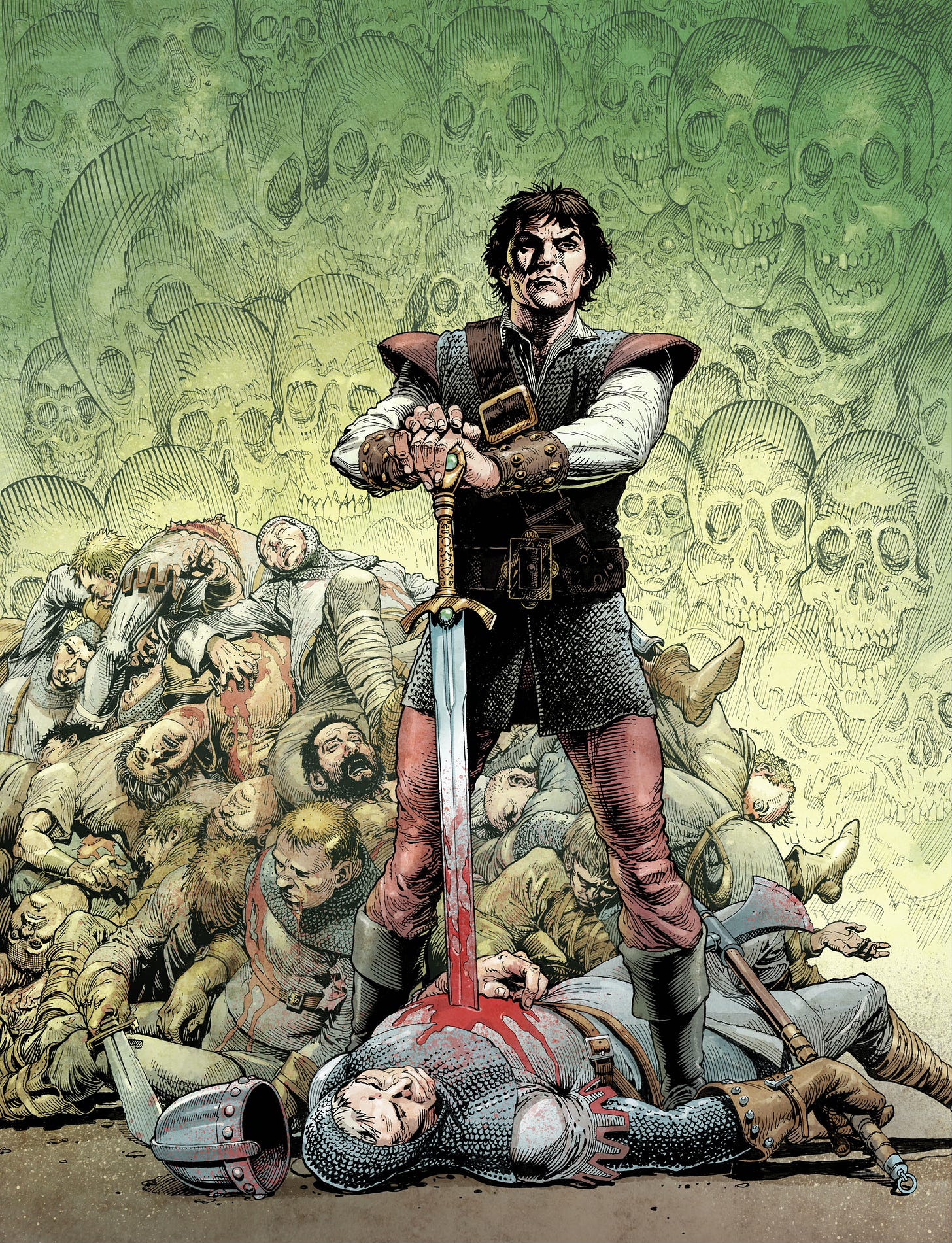

Over three decades after Hawk the Slayer’s UK release during the Christmas hols of 1980, 2000 AD publishers Rebellion acquired gaming and publishing rights to Hawk in 2015. Following a Kickstarter movie sequel, Hawk the Hunter (which didn’t quite make it), Rebellion published a five-part comic-book sequel, Hawk the Slayer: Watch For Me In The Night, written with verve and humour by Garth Ennis (Preacher, The Boys) with seething, vibrant artwork by Henry Flint.3

“I genuinely love Hawk the Slayer, for what I hope are all the right reasons,” Ennis told Nerdist in 2021. “And I wrote this story in the same spirit that I enjoy the film. It’s larger than life, it’s got the sometimes (beyond) hyperbolic language and characterization typical of its genre, it requires massive suspension of disbelief—but it’s got a lot of heart, the story goes in a straight line and never falls apart, the heroes are likable, and the villains are extremely memorable.”

Then there’s the follow-up, Hawk the Slayer: The Last of Her Kind, written by myself4 with brooding artwork by Simon Coleby, the first episode of which lands in this year’s Christmas edition of 2000 AD.

For me, Hawk was canonised via repeated taped-off-the-telly viewings on VHS, which was a lot cheaper than the multiple rentals of Krull that I craved. Aside from the Dungeons & Dragons animated show, I was starved of then-modern movies featuring the kind of sorcerous adventures I was reading in Deathtrap Dungeon and Warlock of Firetop Mountain. I wasn’t old enough to watch Excalibur or Milius’s Conan, so when it first aired on ITV in May 1985, Hawk the Slayer ended up being my go-to fantasy movie fix. Somehow the sight of Hawk and his mates storming a monastery amid volleys of fluorescent ping-pong balls (a “whirlpool of flying firebolts”, apparently) was indescribably thrilling.

In writing my 2005 book Empires of the Imagination: A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema, I was determined to set my rose-tinted glasses aside, though my evaluation of Hawk the Slayer was perhaps a little too sober. As the years passed, Hawk stuck with me for reasons beyond nostalgia. Unlike the Californian canyons of Beastmaster or the Spanish sierras of Conan, Hawk’s muddy Britishness made the fantasy feel tantalisingly close to home, as if that grim world of perilous adventure wasn’t quite so far away after all.5 As with the warehouse never-worlds of The Dark Crystal (1982) and The Company of Wolves (1984), Faerie seemed to lurk somewhere not over the rainbow, but on the other side of the M25.

But Hawk invites the imagination in other ways. Like Star Wars (1977), Hawk makes frequent use of what Professor Matt Hills calls “hyperdiegesis”, “the creation of a vast and detailed narrative space, only a fraction of which is ever directly seen or encountered within the text.” The Clone Wars, Tosche Station, the Kessel Run, all hyperdiegesis. Much of the dialogue in Hawk works in the same way, fleshing out the distant corners of the world as travellers speak of archery tournaments in Brackley, of wizards gathering in the south, of northern barons hoarding plunder. Where’s Brackley? Who are these wizards and why are they gathering? The absence of answers prompts you to visualise everything you cannot see. Perhaps the reason why the worlds of Star Wars and Hawk are so fondly remembered – and why we can be so fiercely protective of them – is because our imaginations have played such a vital role in creating them.

For a movie famed for its shortcomings, it seems Hawk the Slayer does a great deal very well indeed.

Hawk the Slayer is in fact a milestone of sword and sorcery cinema. It was first out the gate during the early ‘80s fantasy boom that erupted in the wake of Star Wars, preceding Clash of the Titans, Excalibur, Dragonslayer, Beastmaster, The Sword and the Sorcerer (all 1981), The Dark Crystal, Conan the Barbarian and Destroyer (1984), Krull, Fire and Ice (both 1983), the lot!

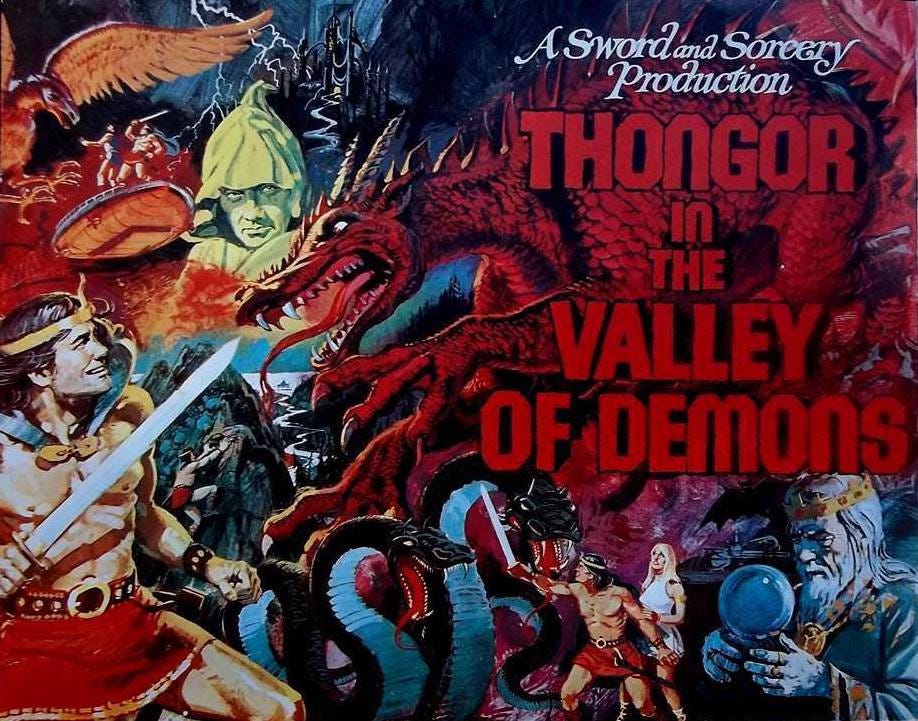

Hawk was almost beaten to the punch by producer Milton Subotsky, co-founder of British horror studio Amicus. Subotsky had been angling for the rights to Conan since the late sixties (at one point, he approached bodybuilder and sith lord Dave Prowse for the role). Subotsky settled instead for Lin Carter’s more family-friendly barbarian Thongor. No doubt sensing the broadening cultural appeal of the fantasy sub-genre, Subotsky formed Sword & Sorcery Productions in 1975 and hoped to make Thongor into a monster-heavy adventure like his Edgar Rice Burroughs movies The Land That Time Forgot (1974) and At The Earth’s Core (1976). United Artists picked up the project at Cannes in 1978, then dropped it six weeks after Screen International announced Thongor in the Valley of Demons was good to go.6

Hawk the Slayer was also the first modern sword and sorcery movie, that is, one not adapted from heroic myth like the Italian Hercules pictures or Harryhausen’s swashbuckling Jason and Sinbad, but conceived by a writer-director fluent in the founding texts of 20th century sword and sorcery fiction. Robert E. Howard’s Conan and Solomon Kane stories, Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and Gray Mouser, Jack Vance’s Cugel the Clever, Marcel had read and loved them all, remaining an avid fantasy fan throughout the seventies while assistant directing on movies including Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (1977) and several Blake Edwards’ Pink Panther movies.

It was while working on his directorial debut, Why Not Stay For Breakfast (1979), that Marcel befriended film composer and fellow fantasy fanatic Harry Robertson7. Marcel pitched him an idea about relocating A Fistful of Dollars to lawless medieval England. “Originally, it wasn't a sword and sorcery story,” Marcel told Martin Sheffield of the British Entertainment History Project in 2022. “The idea was we were going to do a sort of medieval version of the Japanese sword films.”

Bashing out a first draft while on holiday in Spain, Marcel had an image in mind of a wandering English badass, a rogue knight having returned from the crusades with an immense broadsword strapped to his back. But Marcel couldn’t figure out the best way for the hero to draw such a cumbersome weapon. “I thought, why don't I make this a magic sword that he can summon into his hand. And that's where it turned from a sword movie into a sword and sorcery movie.”

Marcel and Robertson managed to secure a budget of £600k8 from Chips Productions, a subsidiary of Lew Grade’s TV distribution company ITC. “And we got called into Lew Grade’s office, Harry and I,” Marcel says. “We thought he was going to pull [the movie]… And he said, ‘Sword and sorcery. I like it.’ He said, ‘What I'd like to do guys,’ he said. ‘Let's forget the £600,000 budget. Why don't we make it into a big major movie, but you [Marcel] can't direct it and you [Robertson] can't produce it. But you can be executive producers. What do you think?’”

Marcel and Robertson were too in love with their vision to give it up. They turned down the golden handshake and chose to make Hawk the Slayer their way.

Faults with the finished picture are many and obvious: Jack Palance’s gothic performance (Marcel admits he pretty much left Palance to get on with it), the lopsided dialogue, the chaotic fight scenes, and the 1970s Doctor Who-level special effects9.

The movie’s less hilarious achievements have been largely ignored. As veteran storyteller Garth Ennis points out, Hawk the Slayer’s plot is perfectly sturdy and gallops along as any good adventure story should. Palance’s Voltan makes for a suitably fearsome villain, his operatic bark equalled by a murderous bite. And who’s talking about that terrific supporting cast? The Rocky Horror Picture Show’s Patricia Quinn as a sightless, whispering witch, Annette Crosbie as the kidnapped abbess, Roy Kinnear as a quailing innkeeper, Christopher Benjamin as a melodious backstabber named Fitzwalter, Warren Clarke as a snarling witch-botherer, and Declan Mulholland as a slave-master with worse table-manners than Jabba the Hutt10.

The synthesiser score by Harry Robertson? It’s genuinely brilliant. Jeff Wayne meets Ennio Morricone with a dash of disco laserbeam. Yet it works perfectly, beguiling, romantic, exhilarating, one of the best fantasy movie soundtracks of all time.

Yet for all its Boys Own exuberance11, Hawk the Slayer harbours a thread of melancholy. The hero’s three non-human comrades – the giant, the elf and the dwarf – are each the last of their kind, their homelands long destroyed. “At night. I can hear the call of my race,” says Crow the elf (in that weird robo-Shatner monotone of his.) “They wait for me. Once I join them. We will be. Forgotten.” As in John Boorman’s Excalibur, there’s a sense here of the pagan world fading, replaced by whatever God it is those nuns are praying to.

“I yearn for the old days,” says Gort the giant, patting his middle-age spread, echoing the sentiment of the movie’s ageing male fanbase who so loved this movie when they were boys. “The iron hills are no more,” says Baldin the dwarf. “If I am to die, why not amongst friends?”

Contrary to common belief that Hawk the Slayer was a box-office flop, the movie did well in the UK, though was never released in the US due to the collapse of its distributor ITC. Forty years on and the movie continues to sell to territories worldwide.

Marcel (now in his eighties) remains cheerful and content in interviews, unfazed by faltered sequels12 and cancelled TV spin-offs, gratified by the cult he inspired by sticking to his sword.

Integrity is another factor in Hawk the Slayer’s peculiar resonance. The movie never wavers in its commitment to its own vision. Marcel never winks at the audience, never talks down to them, never breaks the fourth wall to say ‘I’m better than this’ in the hope of scoring a more respectable gig. It’s this sincerity that would qualify the movie as ‘Camp’ according to Susan Sontag, who stated in her 1964 essay Notes on Camp, “The essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails.”

But that seriousness is also the very ingredient that makes the fantasy work.

Belief.

Neither Conan nor Tinkerbell can live without it. All fantasy, but sword and sorcery and epic fantasy in particular, must pledge itself to its own wild premise. Jokes, doubt, self-consciousness, snark, all these do is tarnish the magic. Let the hipsters and sceptics laugh. They’ll never know how it feels to soar within that dream.

It’s that vision which sustains Hawk the Slayer, Marcel’s concept of the knight errant, the Gawain-With-No-Name roaming the bandit-haunted woods of pagan Britain in search of mystery and adventure. Yes, it’s hackneyed, but it’s coherent, even when the movie itself is far from coherent.

Even after Hawk has ridden into the sunset and the credits have rolled with a raptor’s scream, we can still see the hero living his adventures, legends yet to be told.

Stay weird.

Hawk the Slayer is available to stream on Apple TV and Amazon Prime.

It’s also available of DVD and Blu-ray, though it looks like you’ll have to dig around for it. Try eBay…

Hawk the Slayer: Watch For Me In The Night by Garth Ennis and Henry Flint is available as a graphic novel from the Rebellion webstore, World of Books and Amazon.

Hawk the Slayer: The Last of Her Kind is a ten-part series, the first episode appearing in the Christmas edition of 2000 AD, now available for pre-order.

Sources

The British Entertainment History Project (interviewer Martin Sheffield, 2022)

The Fantasy Podcast (Oliver McNeil, 2015)

Rebellion (Rob Power, 2015)

Starburst (Paul Mount, 2015)

The Guardian (Nick Curtis, 2015)

2 Warps to Neptune (author unknown)

Cool Ass Cinema (author unknown)

With thanks to Steve Green and Barrington Boots of the 2000 AD Online Forum.

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

One of the movie’s swords recently went to auction with an opening bid of £18k.

Seriously, if it’s sword and sorcery hilarity you’re after, there’s nothing funnier than Aristide Massaccesi’s Ator, the Fighting Eagle (1982), in which Miles O’Keeffe plays a bewildered barbarian in yeti-boots and a Fame headband, the son of Torin “who cast his seed upon the wind”. In a quest to marry his own sister, Ator battles a rickety giant spider, gets snoo-snoo’d by a tribe of lusty Amazons, and picks a sword-fight with his own shadow, like a hair-metal guitarist coming down off his ‘ludes.

Henry Flint, a publicity-shy genius with an explosive imagination, who remains frustratingly under-appreciated outside of Judge Dredd and 2000 AD.

Between this and Black Beth, I continue to make a comics career out of dusting off sword and sorcery curios that everyone else has forgotten about.

Like many Hammer films before it, Hawk was filmed in Black Park next to Pinewood Studios, Buckinghamshire. I went location hunting there once and managed to find the lakeside spot where Baldin the dwarf was tragically rescued from being immolated by Patrick McGee and his slapheaded cultists.

For more on the Thongor that could have been, check out these pieces on Cool Ass Cinema and 2 Warps to Neptune.

Robertson composed the score for a number of British horror films, including Hammer’s The Vampire Lovers (1970), Lust For a Vampire, Countess Dracula, and Twins of Evil (all 1971), as well as Tyburn’s The Ghoul and Legend of the Werewolf (both 1975).

This was more than Terry Gilliam got to create the ingeniously convincing medieval worlds of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) and Jabberwocky (1977), well over double the budget of Holy Grail’s reported £282k and just over Jabberwocky’s £588k. Though £100k of Hawk’s budget went to pay Jack Palance’s fee.

Pinewood kindly allowed Marcel to use whatever sets and props he could find around the studio. I suspect that the glove-puppet monster seen waddling about in the haunted Forest of Weir was recycled from the demon foetus that crawls out of that poor woman in Hammer’s icky To The Devil a Daughter (1976). This flesh-eating forest-dweller is called a ‘Krite’ in Marcel’s script, no relation to the saw-toothed alien muppets of Critters (1986).

Mulholland played the original – human – Jabba in Star Wars, but his scene got cut, only to be resurrected in the ‘Special’ editions as a bug-eyed glob of CGI.

Girls don’t feature too much in Hawk. The nuns tend to cluck and panic and do daft things like letting the bad guys in through the front door. Patricia Quinn’s sorceress doesn’t even get a name, known to the boys only as ‘The Woman.’ Garth Ennis took steps to fix all this by introducing Bella, a cynical, lusty wench, the daughter of Ranulf, Hawk’s crossbow-wielding comrade.

One such project was slated to star a pre-fame Tom Hardy as Hawk.

I always enjoy reading what you have to say about Hawk the Slayer, knowing your absolute love for this genre.

Perhaps one of the reasons why so many love it is the fact they can feel the love of those who made it.