Lessons from Hannibal Lecter: How to Write a Human Monster

Can horror be scary without the supernatural?

What’s so scary about Hannibal Lecter anyway?

He can’t float through your bedroom window or break through walls. He can’t sprout tentacles, drag you to Hell, hunt you in your dreams, or throttle you with telekinesis. Bullets are a grave inconvenience to him, and he would never be so uncouth as to pick up a chainsaw.

He’s just a man, “a small, lithe man. Very neat.”

So how did premier thriller/horror author Thomas Harris make a character with no supernatural powers so damn scary? How can any writer make us fear a monster so seemingly banal?

Demon psychiatrist Hannibal ‘the Cannibal’ Lecter is the star of three Harris bestsellers, The Silence of the Lambs (1988), Hannibal (1999) and an unloved prequel Hannibal Rising (2006)1.

Brian Cox was the first to play him on screen in Michael Mann’s neon-drenched nightmare Manhunter (1986). Cox plays Lecter with subtlety, perhaps too much subtlety for us to see the monster he truly is. It was Anthony Hopkins who immortalised the character as the bug-eyed Mephistopheles wheedling a Faustian bargain out of Jodie Foster in Jonathan Demme’s quintuple-Oscar-winning The Silence of the Lambs (1991)2.

Hopkins’s Lecter was canonised by the American Film Institute as the greatest villain in US cinema history (ahead of Norman Bates and Darth Vader), his prison-issue muzzle now as iconic as Jason’s hockey-mask or Fred Krueger’s backscratcher.

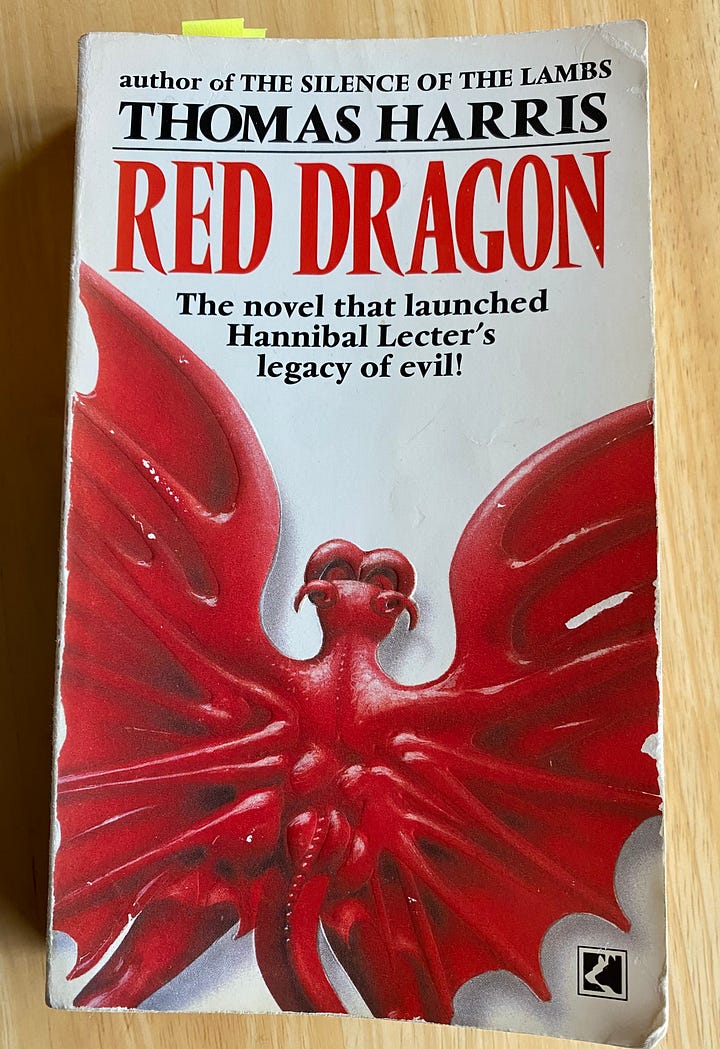

But the character’s debut was a modest one, a sideline role in Harris’s second novel Red Dragon (1981). This benchmark thriller features Will Graham, a haunted FBI profiler with a genius for understanding the psychopathic mind.

But this genius is also poisonous. Will’s empathy for evil is corroding his soul, turning him into the very kind of asocial ghoul that is his quarry.

As a popular horror-thriller Red Dragon is the perfect organism: lean, elegant, merciless, its structural perfection matched only by its hostility. Harris brought gothic horror to the crime novel, Red Dragon and Silence establishing the genre of the contemporary serial killer novel, exemplified by John Sandford’s Rules of Prey (1989), Jeffrey Deaver’s The Bone Collector (1997), Mo Hayder’s Birdman (2000) and Jeff Lindsay’s Darkly Dreaming Dexter (2004).

Like Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster, Lecter is pure gothic: a creature of duality, civil yet savage, courteous yet carnivorous, the physician who cannot heal, only kill. His unfathomable pathology is a haunted castle, a labyrinth that invites and consumes. Lecter is the man-eating ogre of fairy tale, the Big Bad Wolf forever one step ahead of the woodsman’s axe.

Yet his intellect and self-assurance are enviable, his repulsiveness tempered by his attractiveness. It’s what enables him to worm his way into our heads.

Harris worked as a crime reporter in ‘60s Texas and ‘70s New York and has confessed (in the few interviews he’s ever given3) that he’s never had to make anything up when it comes to writing novels.4

Lecter appears early in Red Dragon, in Chapter Seven.

Will has already hit a wall in his pursuit of a psychopath known as ‘the Tooth Fairy’. With the killer due to strike under the next full moon, Will is forced to consult the only person who can equal his own gift for perception: Doctor Hannibal Lecter, another maniac whom Will put behind bars three years ago.

The last time they met outside of court, Lecter succeeded in partially disembowelling poor Will, who must now confront not only the trauma of that encounter, but also the disturbing truth that he is not so dissimilar to the psychos he nails.

Harris doesn’t jump straight into this fearful reunion. He has another supporting character to introduce first, the chilly Dr. Frederick Chilton5, Chief of Staff at the Chesapeake State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

Harris also needs to give us a good reason to fear a man who is safely behind bars when we first meet him.

Chilton welcomes Will into his office, chatty as he offers a chair.

“Frankly, I sometimes feel like Lecter’s secretary rather than his keeper,” Chilton said. “The volume of his mail alone is a nuisance. I think among some researchers it’s considered chic to correspond with him - I’ve seen his letters framed in psychology departments and for a while it seemed that every Ph.D. candidate in the field wanted to interview him.”

This backstory feels smooth and natural because it’s coming from a character who knows Lecter best of all (which still isn’t saying much). By offering these titbits throughout the scene, Chilton reveals as much about his own personality as he does about Lecter.

We’re too curious to find out more about Chilton to notice that he’s burying Lecter-centric exposition the whole time. Why does he seem more irritated by Lecter than fearful of him? The emphasis on those framed letters betrays an envy of his fellow doctor.

Chilton goes on to set the ground-rules for Will’s interview.

“To begin with, Dr. Lecter will stay in his room. That is absolutely the only place where he is not put in restraints. One wall of his room is a double barrier which opens on the hall. I’ll have a chair put there, and screens if you like.”

It feels like we’re preparing to view a tiger at the zoo. The feeling is one of safety and curiosity. Reassurance must be established – a protective wall between us and the monster – before that wall can be gradually broken down as the scene progresses.

“I must ask you not to pass him any objects whatever, other than paper free of clips or staples. No ring binders, pencils, or pens. He has his own felt-tipped pens.”

Moving closer now with suggestions of physical interaction, building a sense of Will approaching the monster. We’re not told why Lecter isn’t allowed to handle paperclips, setting the reader’s mind a-boggle as to what he might be capable of doing with so tiny and innocuous an item.

“I might have to show him some material that could stimulate him,” Graham said.

“You can show him what you like as long as it’s on soft paper. Pass him documents through the sliding food tray. Don’t hand anything through the barrier and do not accept anything he might extend through the barrier. He can return papers in the food tray.”

Will remains focused and taciturn, as eager as we are to be done with the preamble and get to the meeting with Lecter. But Harris isn’t done building suspense, so he has Chilton unwilling to let Will go just yet.

“It may seem gratuitous to warn you, of all people, about Lecter. But he’s very disarming. For a year after he was brought here, he behaved perfectly and gave the appearance of cooperating with attempts at therapy. As a result – this was under the previous administrator - security around him was slightly relaxed.

“On the afternoon of July 8, 1976, he complained of chest pain. His restraints were removed in the examining room to make it easier to give him an electrocardiogram. One of his attendants left the room to smoke, and the other turned away for a second. The nurse was very quick and strong. She managed to save one of her eyes.”

This is the first time we’ve received explicit details of Lecter’s atrocities.

Now we understand why he’s kept under such meticulously high security. He can sniff out the faintest weakness and has the patience of a spider lurking at the fringes of its web. Like the vampire or the werewolf, Lecter’s humanity is just a mask, a predatory ruse, and the monster will come rushing at us when we least expect it.

A terrible threat has been established and it’s beginning to feel like those bars may not be enough to contain the monster. When we finally meet the little man sitting quietly in his cell, it will be in the full knowledge of what he is.

Chilton presents a strip of EKG tape from his desk drawer, a party trick reserved to intimidate visitors. We’re getting a good whiff of sadism from Chilton. He knows how much Will has suffered at the hands of Lecter. (“It may seem gratuitous to warn you, of all people.”) His finger traces the zig-zag that measured Lecter’s pulse during the incident with the nurse.

“Here, he’s resting on the examining table. Pulse seventy-two. Here, he grabs the nurse’s head and pulls her down to him. Here, he is subdued by the attendant. […] His pulse never got over eighty-five. Even when he tore out her tongue.”

Here and with the previous line about saving one of the nurse’s eyes, the description doesn’t linger. It’s as clean and succinct as a surgical incision.

Lengthy and loving descriptions of gore and mayhem risk denying the role played by the reader’s imagination.

Chilton could read nothing in Graham’s face. He leaned back in his chair and steepled his fingers under his chin. His hands were dry and shiny.

Red Dragon is a novel about getting into other people’s heads and Harris’s PoV often drifts between characters within a single scene. We feel it here. We’re in Chilton’s head, reading nothing in Graham’s face. But those ‘dry and shiny’ hands steepled under the doctor’s chin feel like they’re being observed by Will, watching Chilton’s smugness and seething at his crude provocations.

It’s the conflict between these two characters and what it reveals about their personalities that make this expository scene so digestible. Chilton’s dislike of people smarter than himself is delicious, his probing of Will betraying his envy of a man clearly more intuitive than himself – a man who isn’t even a doctor. (Will tells him so upon their meeting.)

“You know, when Lecter was first captured we thought he might provide us with a singular opportunity to study a pure sociopath,” Chilton said. “It’s so rare to get one alive. Lecter is so lucid, so perceptive; he’s trained in psychiatry ... and he’s a mass murderer. He seemed cooperative, and we thought that he could be a window on this kind of aberration.”

Chilton talks about human beings like he’s collecting butterflies. He speaks with arrogance, declaring Lecter “impenetrable”. Chilton has reached the limits of his knowledge and wants to know what Will can add – just as Will must tap Lecter for further inspiration on the Tooth Fairy case.

Chilton asks Will if he has conversed with Lecter for any length of time. Will is uncomfortable and unwilling to go into detail. Chilton presses him, telling Will that Lecter is, “very familiar with you. He’s given you a lot of thought.”

The monster is not only powerful, a definite threat, barely contained, we now learn it’s motivated to visit harm upon Will. The threat goes up a notch. Suspense builds. By now we’re itching to see Lecter for ourselves. But Harris isn’t done teasing and neither is Chilton.

“It’s impossible, of course, to tell what he’s holding back or whether he understands more than he’ll say. Oh, since his commitment he’s done some brilliant pieces for The American Journal of Psychiatry and The General Archives. But they’re always about problems he doesn’t have. I think he’s afraid that if we ‘solve’ him, nobody will be interested in him anymore and he’ll be stuck in a back ward somewhere for the rest of his life.”

Stuck much like Chilton himself, much like Chilton and Will and Lecter are all reflections of each other. The monster feels present in the other characters. No one can quite grasp what Lecter is or how to grapple with him. He’s like that seeping mist in Dracula’s shapeshifting repertoire. By now, those prison bars and security protocols feel terrifyingly insufficient.

“Some of the staff are curious about this: when you saw Dr. Lecter’s murders, their ‘style,’ so to speak, were you able perhaps to reconstruct his fantasies? And did that help you identify him?”

Graham did not answer.

Chilton is a petty monster of pride, ego and spite, a baseline human against whom we can measure the indifference and self-control of the far greater monster lurking in the cell downstairs.

Harris uses Chilton as a goad in this scene, forcing Will to reveal just how emotionally vulnerable he is – the very weakness that Lecter is going to exploit.

Chilton having exposed his Achilles Heel, Will has had enough.

“Thank you, doctor. I want to see Lecter now.”

Why can’t we cut this scene?

Because it’s introducing a supporting character who recurs throughout the novel. It’s also clearing a lot of exposition that would otherwise clutter the next scene, the climax towards which everything is building and which needs to run fast and smooth if it’s to generate any power.

The scene also establishes two crucial factors without which the meeting with Lecter, our brush with death, would lose its scariness: 1.) the overwhelming, uncontainable threat posed by Lecter and, 2.) Will’s specific vulnerability to that threat.

Will is the character most susceptible to the predations of this particular monster. He’s also the person to whom Lecter can do the greatest and most immediate damage.

The protagonist is rendered vulnerable before the monster is unleashed.

It’s a classic horror technique. Think of the opening scene in Jaws. Poor Chrissie is alone, naked, benighted, more than a little high, and floating in an element not her own, and from which she is unable to escape.

The steel door of the maximum-security section closed behind Graham. He heard the bolt slide home.

Graham knew that Lecter slept most of the morning. He looked down the corridor. At that angle he could not see into Lecter’s cell, but he could tell that the lights inside were dimmed.

Graham wanted to see Dr. Lecter asleep. He wanted time to brace himself. If he felt Lecter’s madness in his head, he had to contain it quickly, like a spill.

‘Graham knew’ reminds us these two characters have a terrible history. Lecter’s madness is not a physical threat, but a psychic one. The very words he breathes are a poisonous fume. One does not simply walk into Lecter’s lair.

To cover the sound of his footsteps, he followed an orderly pushing a linen cart. Dr. Lecter is very difficult to slip up on.

The subtle switches to present tense in this scene feel galvanising, immediate. Will is back in the danger zone with the creature who almost succeeded in relieving him of his lower intestine.

He peeks down the hall and sees the steel bars, a nylon net to prevent Lecter from reaching through. Of all the details within, he notices furniture ominously bolted to the floor, stacked with ‘softcover’ books.

‘He walked up to the bars, put his hands on them, took his hands away.’

Harris has Will assuring himself of the solidity of those bars, the certainty of his safety. But are prison bars proof against a thing like Lecter? Everything we’ve so far learned about him undermines any sense of security.

Dr. Hannibal Lecter lay on his cot asleep, his head propped on a pillow against the wall. Alexandre Dumas’ Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine was open on his chest.

Graham had stared through the bars for about five seconds when Lecter opened his eyes and said, “That’s the same atrocious aftershave you wore in court.”

“I keep getting it for Christmas.”

With another twitch of the present tense, Harris notes that Lecter’s eyes “are” dark red and reflect the light like crimson pinpricks, causing Graham to involuntarily smooth the bristles on the back of his neck.

There’s no cliched hammering of the heart, no sickness in Will’s stomach. Harris selects a more unusual, delicate, even sensual response.

“Christmas, yes,” Lecter said. “Did you get my card?”

“I got it. Thank you.”

Dr. Lecter’s Christmas card had been forwarded to Graham from the FBI crime laboratory in Washington. He took it into the backyard, burned it, and washed his hands before touching Molly.

Lecter doesn’t share the supernature of the zombie, werewolf or vampire, but there’s something infectious about him nonetheless, certainly to Will, our focal character.

Permit me a Dungeons & Dragons-related digression.

I used to read Dragon magazine back in the day and was struck by a Ravenloft-adjacent article explaining how DMs can make players genuinely fear the monsters that get thrown at them. The article warned that most players are savvy. They’ve usually got some idea of a monsters’ stats and know that a demi-lich will give them more of a fight than a wandering ghoul.

Therefore, DMs should avoid explicitly naming a creatures’ species when the players encounter it. Set the stage and present the monster through the eyes of a nervous dungeoneer rather than an encyclopaedia-brained nerd. Watch them freak out as they try and figure out what they’re dealing with – even if all they’re facing is a lowly animated skeleton.

Sensation over calculus.

A monster is more than just a bunch of stats.

Keep the players uncertain.

That’s what Harris does with Lecter in both these scenes. The author never reduces the character to any banal certainty.

Yes, Lecter is just a man. Yes, he’s behind bars and can’t lay a finger on us. But Harris ensures we remain entirely uncertain about all that he is and what he is capable of, leaving us forever on guard and deep in suspense.

In Red Dragon and Silence, Lecter is irresistible because he is unknowable. He becomes far less interesting and more of a negotiable pantomime villain the more we learn about his backstory in the later novels.

Lecter’s relationship with Will transcends Lecter’s physical abilities and gives him the power to harm and intimidate. We meet him through the eyes of the person who fears him the most and to whom Lecter means the most.

Will fears Lecter because of what he represents: chaos, violence, madness. He personifies not only Will’s near-death trauma, but the awful truth that he and Lecter are too much alike.

Lecter is courteous and offers Will a chair.

The Doctor’s fabled manners seem to offer a means by which we might avoid his wrath. If we’re nice and polite, he might be persuaded to leave us alone, the way a crucifix might ward off a vampire. But Lecter’s malevolence abides by no such comforting rule - as that poor, half-blinded nurse found out.

The exchange that follows between Lecter and Will wouldn’t feel half as distinct and spontaneous if all that exposition hadn’t been cleared away in the previous scene, greasing the rails for the rollercoaster to come.

Lecter stood until Graham was seated in the hall. “And how is Officer Stewart?” he asked.

Lecter’s courtesy is spiked with malice. He’s testing Will.

“Stewart’s fine.” Officer Stewart left law enforcement after he saw Dr. Lecter’s basement. He managed a motel now. Graham did not mention this. He didn’t think Stewart would appreciate any mail from Lecter.

“Unfortunate that his emotional problems got the better of him. I thought he was a very promising young officer. Do you ever have any problems, Will?”

“No.”

“Of course you don’t.”

Graham felt that Lecter was looking through to the back of his skull. His attention felt like a fly walking around in there.

Will is on guard, but Lecter may as well be psychic.

He lulls Will with a veiled compliment, confiding how sick he is of tedious visits from ambitious, second-rate psychologists.

Will compliments him back.

“Dr. Bloom showed me your article on surgical addiction in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.”

“And?”

Harris doesn’t give us the tone of that ‘and’ and we’re left to wonder what Lecter meant by it. Does he want to know what Will thought of the article? Or asking why Will is bothering to play games?

Lecter is not Dr. Chilton, alas.

Will replies.

“Very interesting, even to a layman.”

“A layman ... Layman-layman. Interesting term,” Lecter said. “So many learned fellows going about. So many experts on government grants. And you say you’re a layman. But it was you who caught me, wasn’t it, Will? Do you know how you did it?”

“I’m sure you’ve read the transcript. It’s all in there.”

“No it’s not. Do you know how you did it, Will?”

“It’s in the transcript. What does it matter now?”

“It doesn’t matter to me, Will.”

Again, Lecter sees straight through Will and nibbles at his Achilles Heel. Which of these two psychos is conducting this interview? Are these prison bars or a mirror?

Will says he wants Lecter’s help. The Doctor figured as much. He’s aware of the Tooth Fairy murders and says he’s been careful to avoid revealing any morbid interest to his captors.

He laughed. Dr. Lecter has small white teeth. “You want to know how he’s choosing them, don’t you?”

“I thought you would have some ideas. I’m asking you to tell me what they are.”

“Why should I?”

Graham had anticipated the question. A reason to stop multiple murders would not occur readily to Dr. Lecter.

More innocent people will suffer unimaginable horrors before they die. Harris reminds us what’s at stake in this scene should Will fail to obtain Lecter’s help.

Will offers incentives. He can ensure Chilton provides Lecter with extra research materials. Lecter bristles at Chilton’s name and confides several insights Will himself noticed about the man from the previous scene.

Lecter seems not only psychic, but omniscient.

“You’d have access to the AMA filmstrip library.”

“I don’t think you’d get me the things I want.”

What does Lecter want? Surely he craves more out of life than foie gras du census-taker and a nice chianti.

Like Heath Ledger’s Joker or Rutger Hauer’s Hitcher, Lecter’s seeming lack of motive is a key factor of his inhumanity. He’s beyond our comprehension, yet there’s the tantalising suggestion that there is something there to comprehend, some method to Lecter’s madness unknown perhaps even to himself.

It’s this paradox that makes Lecter so captivating and more than just Michael Myers with a wine-list.

“I thought you might be curious to find out if you’re smarter than the person I’m looking for.”

“Then, by implication, you think you are smarter than I am, since you caught me.”

The swift articulacy of Lecter’s response is what’s frightening here. That he can pull such an erudite response out of the bag so quickly reveals that he already holds command over the conversation.

“No. I know I’m not smarter than you are.”

“Then how did you catch me, Will?”

Will knows full well how he did it.

He and this sordid killer both think alike.

“You had disadvantages.”

“What disadvantages?”

“Passion. And you’re insane.”

If Lecter was nothing but a cultivated creep with a flamboyant rap sheet, he wouldn’t be very interesting. What intrigues is his personality.

One of his foibles is that discourtesy is unspeakably ugly to him. So when Will delivers his blunt verdict, “you’re insane”, the Doctor is triggered to respond in kind, revealing yet more perilous details about Will.

“You’re very tan, Will.” Graham did not answer.

“Your hands are rough. They don’t look like a cop’s hands anymore. That shaving lotion is something a child would select. It has a ship on the bottle, doesn’t it?”

Lecter has deduced Will has a child in his life.

Dr. Lecter seldom holds his head upright. He tilts it as he asks a question, as though he were screwing an auger of curiosity into your face. Another silence, and Lecter said, “Don’t think you can persuade me with appeals to my intellectual vanity.”

“I don’t think I’ll persuade you. You’ll do it or you won’t. Dr. Bloom is working on it anyway, and he’s the most—”

“Do you have the file with you?”

“Yes.”

“And pictures?”

“Yes.”

“Let me have them, and I might consider it.”

“No.”

“Do you dream much, Will?”

“Good-bye, Dr. Lecter.”

You don’t mess with dialogue this good, which is why Michael Mann left it pretty much intact when writing his adaptive screenplay for Manhunter.

Lecter eventually accedes and Will hands over the file while he waits in the next room. He’s shaken, numb, gathering himself before returning to Lecter for round two.

Lecter sat at his table, his eyes filmed with thought.

Graham knew he had spent most of the hour with the pictures.

“This is a very shy boy, Will. I’d love to meet him... Have you considered the possibility that he’s disfigured? Or that he may believe he’s disfigured?”

They pore over the evidence, sounding like partners working a case, though Lecter fishes for yet more clues about Will’s life. (Go read the novel and you’ll find out why.)

Lecter observes the file’s lack of description regarding the grounds in which the murders took place. He asks what the yards were like. Will tells him.

“Big backyards, fenced, with some hedges. Why?”

“Because, my dear Will, if this pilgrim feels a special relationship with the moon, he might like to go outside and look at it. Before he tidies himself up, you understand. Have you seen blood in the moonlight, Will? It appears quite black. Of course, it keeps the distinctive sheen. If one were nude, say, it would be better to have some consideration for the neighbours, hmmmm?”

We can’t help but laugh. Lecter is indeed disarming (in both senses of the word).

He rambles a little before trying to snag Will’s home number. When Will denies him, Lecter bites him again by asking how Will caught him. Graham walks away. Lecter asks again.

Will escapes, but the damage is done.

Lecter haunts Will like a ghost immune to exorcism.

“He was numb except for dreading the loss of numbness. Walking with his head down, speaking to no one, he could hear his blood like a hollow drumming of wings. It seemed a very short distance to the outside. This was only a building; there were only five doors between Lecter and the outside. He had the absurd feeling that Lecter had walked out with him. He stopped outside the entrance and looked around him, assuring himself that he was alone.

Will visits Lecter in search of the happy ending he wants for this story. To see the Tooth Fairy behind bars, just like Lecter. But as Lecter has reminded him, Will can only capture the Tooth Fairy at the cost of his own humanity, his relationship with his wife Molly and his stepson.

Lecter has imparted a monstrous truth that cannot be staked through the heart, pierced with a silver bullet or laid to rest with arcane rites.

Hannibal Lecter doesn’t need the supernatural to inflict the ultimate disquiet.

Stay weird

Red Dragon remains copyright of author Thomas Harris. Passages are quoted here under terms of fair use for the purposes of criticism.

Red Dragon is available from:

THOMAS HARRIS ON WRITING

“Sometimes you really have to shove and grunt and sweat. […] Some days you go to your office and you’re the only one who shows up, none of the characters show up, and you sit there by yourself, feeling like an idiot. And some days everybody shows up ready to work. You have to show up at your office every day. If an idea comes by, you want to be there to get it in.”

Interview by Alexandra Alter, The Independent, 2019

“I don’t think I’ve ever made up anything,” […] “Everything has happened. Nothing’s made up. You don’t have to make anything up in this world.”

Interview by Alexandra Alter, The Independent, 2019

“It’s funny how in the evolution of a character, if you have some new ones, new characters, the first couple of days you can feel like a window dresser, you’re setting mannequins around. And then, if you’re lucky, and this is the best sign in the world: if they quit cooperating with you. […] The worst mistake you can make is to make a character do something they don’t want to, and the best thing you can do is sit back and let her rip, let ‘em do what they wanna do. You have to in the end.”

Interview by Anthony Brandt, Conversations, LTV Studios, 2019

“It’s useful to imagine an audience sitting in your office, people whose intelligence you respect and you’re trying to hold their attention and want to keep them engaged.”

Interview by Anthony Brandt, Conversations, LTV Studios, 2019

“I’d rather dig a ditch 60 feet long than to do one day’s work of writing. That is how it feels to me. It is very difficult.”

Paraphrased by Joe Pintauro, interview by Joel Achenbach, The Washington Post, 1999

“I dreaded doing Hannibal, dreaded the personal wear and tear, dreaded the choices I would have to watch, feared for Starling. In the end I let them go, as you must let characters go, let Dr. Lecter and Clarice Starling decide events according to their natures. There is a certain amount of courtesy involved. As a sultan once said: I do not keep falcons – they live with me.”

Foreword to a Fatal Interview, Thomas Harris, 2000

YOUR NEXT READ

If this post got you smiling, thinking or ready to create, then please…

Or…

Every drop of reader support helps this project grow!

Legend has it Harris wrote this book under duress when movie-producer Dino De Laurentiis ran out of Hannibal source material and threatened to make another movie based on original material conceived by another writer. De Laurentiis produced the first Lecter adaptation Manhunter (1986), a flop turned cult classic, so he passed on producing the follow-up, Silence of the Lambs (1991). When that movie scored big, Dino wanted back in and produced both Hannibal (2001), Red Dragon (2002) and – eventually – Hannibal Rising (2007).

Hopkins reprises the role with less success in Ridley Scott’s Hannibal (2001) and Brett Ratner’s Red Dragon (2002). Gaspard Ulliel plays a teenage Lecter dining on Nazi rindersteak in Peter Webber’s WWII-set prequel Hannibal Rising (2007), while Mads Mikkelsen’s eerie performance as Lecter over three seasons of TV’s Hannibal (2013-15) is one of the least talked about, yet perhaps the best of all.

Harris has written six novels over his fifty-year career and given even fewer big interviews.

Harris was once sent on assignment to Nuevo León state prison in Monterrey, Mexico, where he met a charitable local doctor. The man was so eerily courteous and inquisitive that Harris was shocked to find out he was an ex-convict known as ‘The Werewolf of Nuevo León’, having served 20 years for killing and dismembering his lover. Harris may also have been inspired by Alonzo Robinson, a serial murderer and cannibal who became a popular boogeyman when Harris was growing up in Mississippi.

Harris has an ear for evocative, literate names. ‘Will’ evokes the force of mind that Graham must wield against his opponents, while Lecteur is masculine French for ‘reader’.

What an education. I'm currently writing a villain and know I haven't made her dark enough. This has inspired some ideas. I've read all the Hannibal books but a long time ago. Must revisit. Thanks so much.

Really good, in depth article Alec. I’m with Dave above, I preferred how Brian Cox played the character but the Lecter was all Grand Guignol in Silence which was good fun too

I remember reading that article from Dragon and thinking it was a really good idea but our DM couldn’t be bothered with all the extra descriptions of monsters and just showed us the pictures! 😁